I stood in front of the Hotel Granvia for about a half an hour, and as I waited for you I couldn’t help wondering what on earth “Granvia” was supposed to mean.

Was it a reference to Madrid’s Gran Via, literally “Great Way”, the so-called “Broadway of Spain”, the street that never sleeps? And if so, what did that have to do with sedate Kyōto, a city where many restaurants close as early as nine in the evening? Or was it in some way an allusion to the “Great Vehicle” of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Probably not. Most likely, the owners just liked the “sound” of it.

These silly, often meaningless names that architects and planners insisted on slapping on buildings, even here in Kyōto, the very heart of Japan, often made me wonder if the Japanese hated their own culture and language.

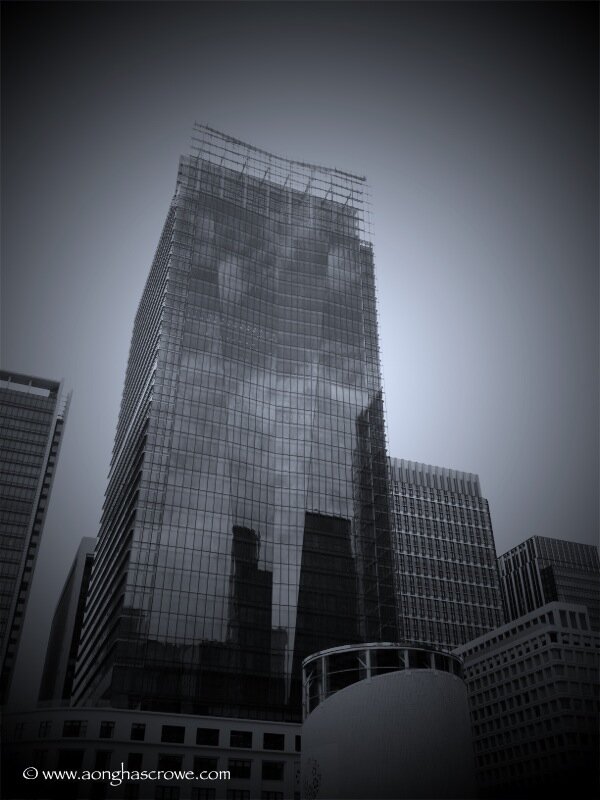

Unfortunately, the folly wasn’t limited to naming. Infinitely worse, it expressed itself in monstruments like the awful Kyōto Tower that stood across the street from me like a massive cocktail pick. A fitting design, because the people who had the bright idea of creating it must have been drunk.

The bombings of WWII, which reduced most Japanese cities to ashes, spared Kyōto for the most part, meaning the ancient capital is one of the few cities in Japan with a large number of buildings predating the war. Or shall I say, was. Because that which managed to survive the war proved no match for wrecking balls, hydraulic excavators, and bulldozers.

“Stupid! Stupid! Stupid!” I muttered to myself.

“Are you talking about me, Sensei?”

Turning around, I found you and . . . wow.

You were wearing a simple short-sleeved, casual tsumugi kimono with a subdued green and yellow plaid design. The obi, though, was a flash of bright autumn colors—oranges and reds—and all held in place, like the string on a present, with an obijime silk cord olive in color. In your short hair, which had been done up with braids, there was a simple kanzashi ornament.”

“You like?”

“I love!”

“I started taking tea ceremony and kitsuke lessons after moving to Kyōto . . .”[1]

“When in Rome . . .”

“Yes, well. I thought I might as well make the most of my time here.”

“You look gorgeous.”

“Thank you.”

You took my arm and in the Kyōto dialect asked how I was feeling: “Go-kigen ikaga dos’ka?”

“Much better, now.”

“So, where are we going?”

“That depends on you.” I would have loved to take you straight to my hotel room and tear that kimono right off of you, but . . . “What do you want to do? Are you hungry?”

“Actually, I am.”

“Okay, then. What are you hungry for?”

“Anythi . . .”

“Stop it! Now think. What is something you’ve been dying to eat, but haven’t . . .”

“Sushi!”

“In Kyōto? The sashimi at my local supermarket in Hakata is much better than what you’ll find in this landlocked town.”

“True, true,” you said, nodding. “How about tempura, then?”

I didn’t have the heart to tell you I’d just had some, so I directed you towards the taxi stand and said, “I know just the place.” And, off we went.

In the cab, I rattled off directions to an upscale tempura restaurant in the Komatsuchō neighborhood of Higashiyama, halfway between Kiyomizu-dera and Yasaka Shrine. I then called the restaurant to warn them that we would be there.

“Are they still open?” you asked.

“Last order’s in about half an hour. It’ll be a squeaker, but, trust me, it’s worth it.”

“What’s the name?”

“Endō.”

“Endō?”

“Endō.”

“Is it famous?”

“Famous enough, I suppose. I like the old house and the neighborhood that it is in more than food itself, to be honest.”

Before long, the taxi pulled up in front of Tempura Endō Yasaka. I got out first and took your hand to help you out of the backseat. When you stood up, you continued to hold on to my hand, gently, but tight enough as if to say “Don’t let go”, so I didn’t. And warmth radiated from my chest to my extremities, like sinking neck-deep into a bath of hot water, and I almost lost my footing going up the short flight of stone steps leading up to the restaurant.

“Are you okay?” you asked.

“Haven’t felt better in years.”

The proprietress, dressed in a lovely kimono the color of autumn ginkgo leaves and a colorful obi made of Nishijin-ori, stood at the genkan and greeted us in the local dialect, “Okoshiyasu.”[2]

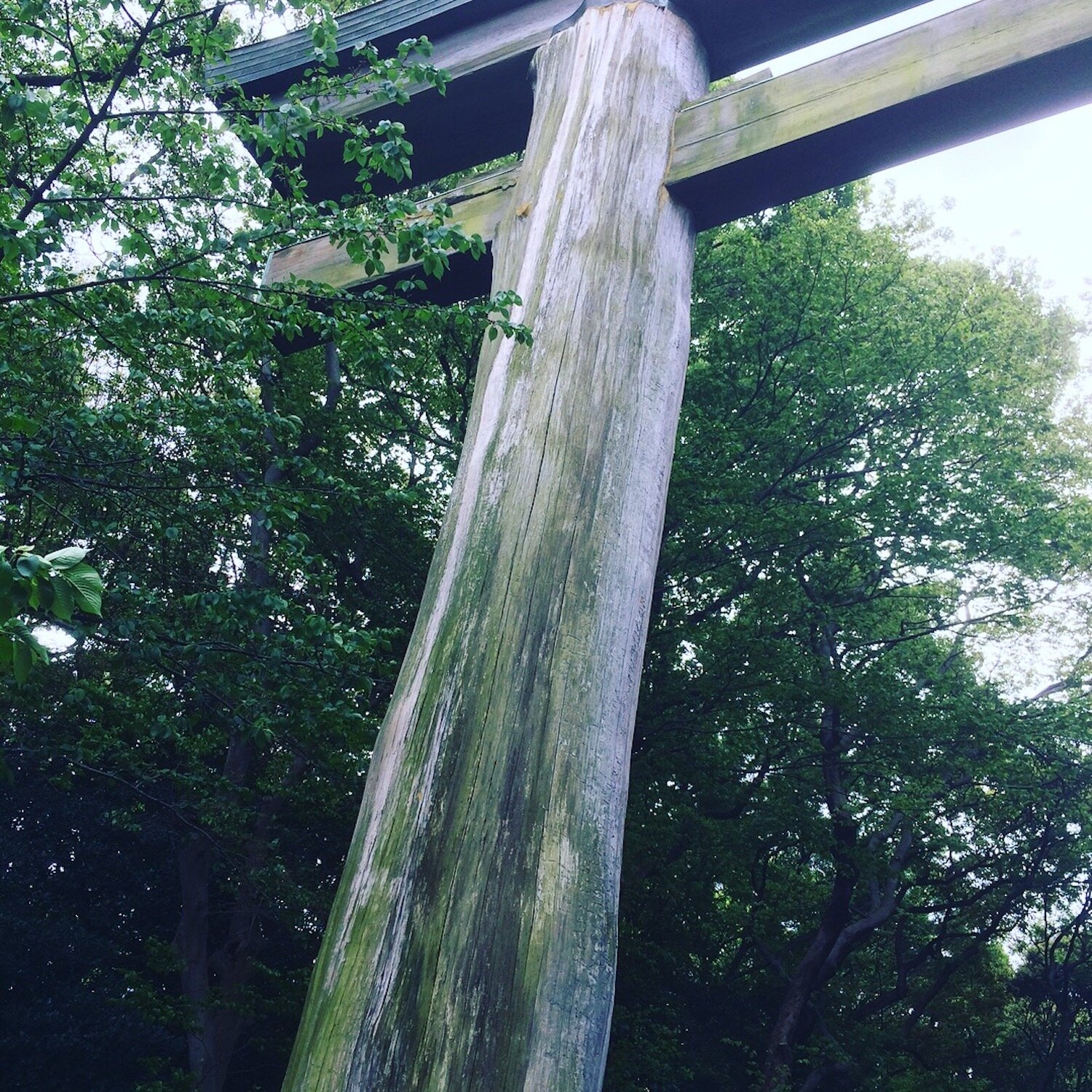

We were led through a narrow hall with earthen walls and exposed cedar posts and beams, to a private Japanese-style room with tatami floors, a low-lying table for two, and a tokonoma alcove in which was hung a scroll with illegible calligraphy on it. Outside the glass doors was a modest garden, no bigger than the room we were sitting in, but ablaze in color because the leaves on the maple trees had already turned.

“How lovely!” you exclaimed as we entered the room.

“I knew you would like it.”

We sat down opposite each other at a table so small our knees touched, but I didn’t mind and I don’t think you did, either.

Shortly after ordering lunch, a tokkuri of good nihonshu at room temperature and two o-choko cups were brought to the table. You took the tokkuri and filled my o-choko with the saké, then you filled your own.

“Kampai!” we chimed and knocked the saké back.

“Ah, I needed that!” you exclaimed.

“Oh?” I said, refilling your cup. “Is it stress?”

“Yes! There’s an older woman at work . . .”

“O-tsuboné?”

You grimaced and took a nip of saké.

The o-tsuboné is a legendary fixture in Japanese offices. These proud, usually single female veterans of the office are capable and efficient, but often harbor a thinly veiled resentment of their younger female coworkers who are fawned over by the men in the office. The term originally referred to women of the Imperial Court or in the inner palace of Edo Castle who were in a position of authority.[3]

“The battle-axe won’t give me a break,” you said, emptying your choko. “Every day it’s something. I waste too much paper when making photo copies. I forgot to turn off the light in the ladies’ room. My slippers are dingy and put customers off when they visit. The tea I made in the morning was too bitter. I didn’t fill out some stupid form the right way . . . Ugh . . . That woman—and I’m starting to suspect that she really isn’t one—didn’t even go to college and she’s bossing me around? I sometimes wonder if the person I came down here to replace didn’t get knocked up just so she could escape from that . . . that bitch.”

I filled your choko with saké.

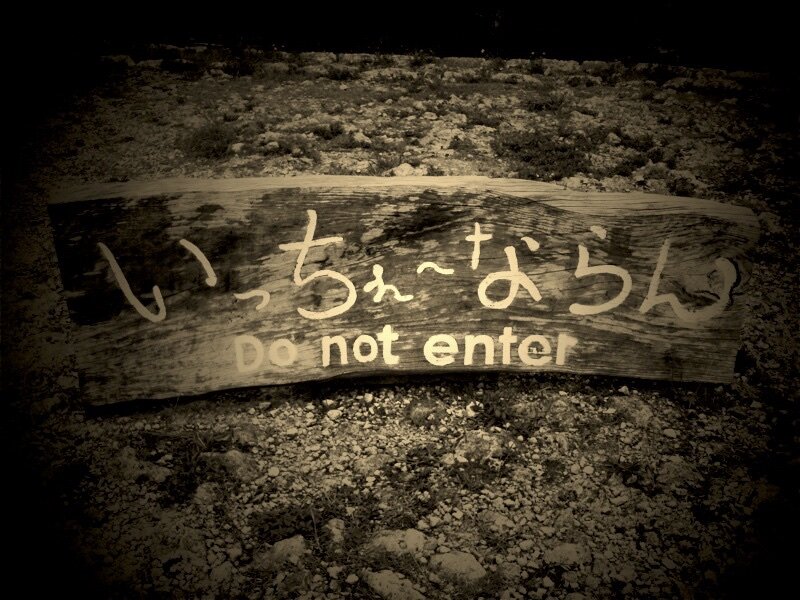

“And to top it all off, she speaks with the harshest Kansai dialect. Every day it’s Akan this! Akan that! Akan! Akan! Akan![4] I’m sorry. I’ve said far too much.”

“Not at all. Get it all out.”

“I never realized how different the . . . the ‘culture’ could be from one prefecture to the next until I started living here. At first, I thought it was just the dialect. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that the language reflected the mood of a place.”

“Yea?”

“Take ‘Akan’ for example. Conversations here often start off on a negative note. In Hakata, we ask ‘Is it yoka? Is it okay, if I do this or that?” Here, it’s always: ‘If I do this or that, will it be akan? Will it be wrong? Will you get angry?’”

“Interesting. I never thought of it that way. But now that you mention it . . .”

“I really don’t want to talk about it, or that bitch, anymore. So, how’s your work going?”

“Like a dream. I’m busier than ever, but . . . It doesn’t really feel like work.”

“It must be nice.”

“Oh, trust me, I, too, have had my fair share of o-tsuboné, too.”

“At the university?”

“No, no, no. Long before I ever started teaching at the university level.”

“Tell me about it.”

“It’s much too long a story and I wouldn’t want to bore you with lurid tales of jealousy and heartbreak and back-stabbing.”[5]

“Now you have to tell me!”

“Someday, perhaps.”

And then you asked if I had taken my seminar students to the farmhouse.

“No.”

“Oh? Why not?”

“To be quite frank, I knew it wouldn’t be the same without you . . .”

Your tone changed markedly: “Sensei, I hope you haven’t been doing those sorts of things for your own benefit. The students are there to be taught by you, to learn from you, to be inspired by you. They aren’t just there for your entertainment.”

“I know. I know. And I agree with you completely. It’s just that your participation last year, your presence had a way of raising the whole experience to a new level. After you graduated, I knew it would be . . . Let’s just say, yours is a hard act to follow. I knew it would be impossible to fake the enthusiasm, so I decided to take a break. At any rate, this new project, H.I.P. . . .”

And then you burst out laughing.

“Hip!”

Now whenever I say H.I.P. I can’t help but laugh, too, which, I’m afraid, has a way of taking all the urgency and importance of the project.

“But, you’re right. I should be thinking more about the students’ needs and less about mine.”

“Atta boy,” you said, patting my hand.

Just then the waitress arrived with two trays of exquisitely presented food. I held up the empty tokkuri and gestured for another bottle of nihonshu.

Even though I wasn’t all that hungry—I had eaten a tempura teishoku set meal only an hour and a half earlier—the food at Endō was just too good not to dig in: delicately fried garland chrysanthemum, fresh wasabi leaves, slices of satsumaimo sweet potato and yamaimo yam, burdock root, crisp lotus root, and on and on. By the time we were finished I was ready to explode.

As the waitress knelt down besides us and began clearing away the dishes, the proprietress came into the room and asked in her soft Kyōto dialect if we would like some bubuzuke.

“Bubuzuke?” you asked. “What is that?”

“It’s a kind of chazuke.” Bubuzuke, I explained, was a light dish of rice topped with a variety of ingredients such as pickles or small bites of fish, wasabi, and confetti-like seaweed called momi nori sprinkled on top. Over all of this is poured piping hot green tea.

“It sounds wonderful,” you interjected. “I’d love some!”

“No thank you,” I told the hostess firmly. “I’m afraid we haven’t got the time . . .”

Kana, the look you gave me could have killed, so once the hostess and waitress had left the room, I whispered: “I’ll tell you all about it once we’re outside.”

Later, as we walked up Yasaka Dori, the Yasaka no To Pagoda of Hokan-ji rising ahead of us, I explained that in Kyōto asking a guest if he wanted some bubuzuke was the passive-aggressive equivalent of tossing him out the window.[6]

Hearing this, you softened, stepped closer to me, and took my arm.

“How did you get to be so smart?”

“I hope to God that this isn’t smart.”

“No, seriously.”

“Well, by asking questions, for one. By being curious. By wondering why things were the way they were. By reading . . .”

Just before we reached the pagoda, I asked: “You’ve been to Kiyomizu-dera, right?”

“Yes.”

“Good. Then, there’s no reason for us to go there today and deal with the crowds.”

We turned left and headed north down a narrow, cobbled road. Before long, the hordes of tourists posing with their goddamn selfie-sticks thinned out, then disappeared altogether, and we were walking slowly along a quiet street lined with clay walls, old houses and Buddhist temples.

“It’s these subdued pockets, like this neighborhood, not the famous temples and their gaudy souvenir shops and matcha ice cream stands, that are the real charm of Kyōto,” I said. “Unfortunately, the people of Kyōto don’t seem to know it.”

I could have walked all day with you on my arm, but by the time we had reached Chion-in, I could see you were tired. We climbed the stairs leading up to the massive, wooden sanmon gate of the temple and sat down. The city of Kyōto spread out before us, the western mountains—Karasuga-daké, Atago-yama, Taku-san—beyond it.

“Your feet must be killing you,” I said.

“It’s not just my feet.” You gestured at the obi that was tied tightly around your waist. “I want to take this off.”

And I wanted to help you out of it, but judging by the small handbag in your lap, I suspected that you hadn’t brought so much as a change of tabi socks with you.[7]

It was still only three-thirty in the afternoon, but it felt much later, as if evening was fast approaching. Living as long as I had in Hakata, in the southwest of Japan, I took it for granted that the sky remained light well into the evening, but here. The combination of the coordinates and the mountains to the west, meant shadows started to grow much earlier.[8]

“Do you have a curfew?” I asked half-jokingly.

“I do, actually.”

“Really?” I didn’t know whether to be appalled or amused.

“Yes. They’ve got me housed in a company dorm. It’s only temporary, of course, because I might be transferred again in the spring.”

“Is that what you’re hoping for?”

“Yes. No. Oh, I don’t know. I like this town, believe it or not, and want to get to know it better, to explore every part of . . .”

I was dying to explore every part of you.

“. . . but there’s that horrid woman in my office.”

“The o-tsuboné.”

“If it wasn’t for her, I’d be quite happy to live here for a year or two.”

“So, what time’s your curfew?!”

“Ten-thirty.”

“TEN-THIRTY!”

“Silly, isn’t it?”

“I didn’t realize you had to take your Holy Orders when you joined the company.”

“I do sometimes feel like a nun.”[9]

“Unbelievable. Say, Kana, have you been to Shōgun-zuka?”

“I don’t think so.”

“You would know if you had.”

“Where is it?”

I pointed to a flight of stairs behind us: “Five hundred meters up.”

“You don’t expect me to . . .”

“No, no. There is a mountain path that leads up to the top, but, don’t worry, we can hail a taxi and get there in about ten minutes.”

“Let’s go then.”

Part of the Shōrenin temple complex in the eastern mountains of Kyōto, Shōgun-zuka is a two-meter-high mound at the top of the mountain, buried inside of which is a clay statue of a general, or shōgun, adorned with armor, an iron bow and arrow, and swords.[10] Near the mound is the Shōgun-zuka Seiryū-den, a prayer hall, behind which is a broad wooden deck that offers one of the best views of Kyōto and the surrounding mountains.

“I never knew this place existed,” you said, and hurried excitedly to the edge. “It’s lovely.”

“Beats the view from that god-awful Kyōto Tower, doesn’t it? What on earth were they think . . .”

“Oh, I can see my dorm from here!”

“Where?”

“See the station?”

“How could you miss it?” The modern station was almost as insulting to the history and sensibility of the city as that ugly tower.[11]

“See where the train tracks cross the Kamo River there?”

“Yes . . .”

“The next bridge just to south is Kujō. Go west from there and you can see a large apartment building.”

“That’s where you live?”

“No. I live near that. How ‘bout you? Where are you staying?”

“The Monterey,” I answered. And, standing close behind you, I placed my left hand on your obi, and took your right hand in mine. Pointing it to a large rectangle of green in the center of the city, I said: “You know what that is, don’t you?”

“Kyōto Gyoen.”

“That’s right, the Imperial Palace and Gardens. Now follow that line from the southwestern corner of the gardens and continue south past that big thoroughfare, Oiké Dōri, and down about two blocks. Right about . . . there, I think.”

Your cheek rested gently against mine, so I put my hands around your waist, pulled you in tight and listened to you breathe . . . in . . . and . . . out . . . slow . . . and . . . deep . . . in . . . and . . . out.

“Sensei?” you began slowly, in a hushed voice. “I want to go to you to your hotel room, but . . .”

“But, what . . .?”

“But I . . . I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“That stupid curfew, for one. But, more than that, I have to be at work by seven-thirty tomorrow morning.”

“So early?”

“The president of our company will be paying us a visit with some local officials. That’s why I couldn’t get away this morning. We had to get everything in order. We only had one days’ notice. I’m so sorry.”

“Kana, don’t apologize. I didn’t come to Kyōto today with any assumptions. I came here to see you. And I have. And I couldn’t be happier.”

You turned around in my arms and pressed your face into my chest and I thought my heart would explode.

“Will you come to see me again soon?”

“Of course, I will.”

You looked up and gave me the biggest smile. I probably should have kissed you right then and there, but we weren’t alone on that deck. And besides, who, but perhaps an uncommitted cenobite, would want his first kiss to be at a Buddhist temple?

We remained on the deck for several minutes more and watched the sun set over the western mountains.

“If you don’t mind,” you said after a while, “there’s a place I’d like to you to take me.”

“Oh? And where would that be?”