Usui 雨水 Yǔshuǐ (19 February ~ 5 March)

According to the traditional Chinese calendar, which divides the year into 24 solar terms (jieqi, 節氣 in traditional Chinese; sekki, 節気, in Japanese), Usui (雨水, Yǔshuǐ in Chinese) is the second mini season of the year. Lasting from roughly February 19th to March 5th, Usui means “rain water”. It is the time when the first day of spring has passed and we begin preparing for the arrival of full-fledged spring. Falling snow becomes rain, and the snow and ice that have accumulated over the past several weeks melt and turn into water.

Kasumi 霞

The phenomenon in which distant objects appear blurry due to water vapor in the air and the faint cloud-like appearance that appears at this time is called kasumi, or “haze”.

Although similar to fog (霧, kiri), it is usually called kasumi in spring rather than kiri, which is the term usually reserved for the mist that occurs in autumn.

春なれや

名もなき山の

薄霞

Harunare ya

Namonaki yama no

Usugasumi

“Spring and the thin haze of a nameless mountain”

This is a haiku by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), the famous haiku poet from the early Edo period. Looking at the thin mist that hangs over the nameless mountain, you can see that spring is in the air.

The ethereal haze hanging over the foothills of mountains and lakes can sometimes appear otherworldly, magical.

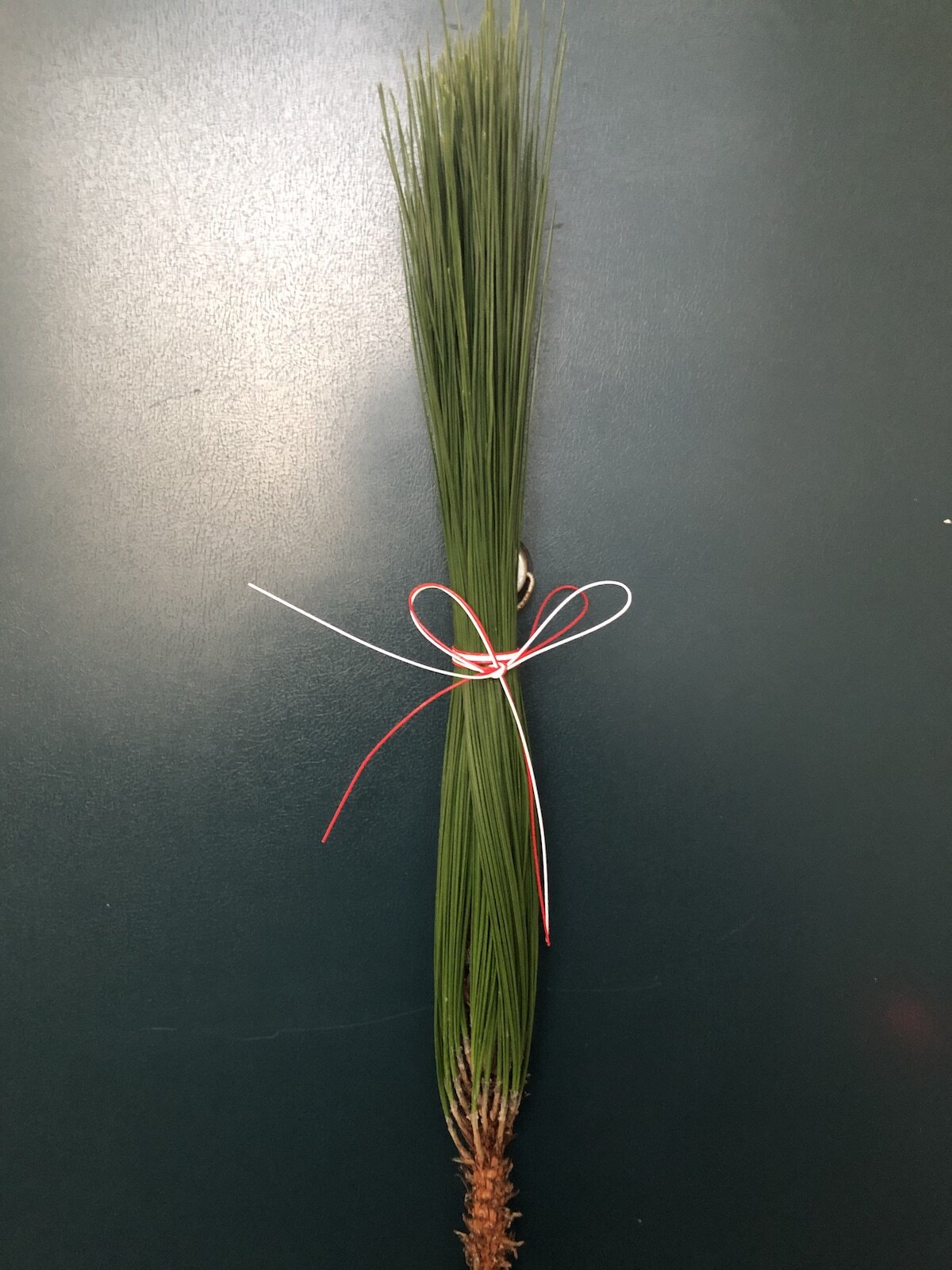

Nekoyanagi 猫柳

The Pussy willow is a deciduous shrub belonging to the Salicaceae family, which produces dense silvery-white hairy flower spikes in early spring.The flower spike of the pussy willow resembles a cat's fur, which is—no surprise—how it got its name.

Known as neko yanagi in Japanese (猫柳, lit. “cat willow”), the plant is also called senryu (川柳, lit. “river willow”) because it often grows alongside rivers.

The haiku poet Seishi Yamaguchi (1901-1994) wrote the following poem.

猫柳

高嶺は雪を

あらたにす

Nekoyanagi

Takane wa yuki o

arata ni su

“Takane Nekoyanagi renews the snow”

The silver-white fur of the nearby pussy willow shines, and perhaps the high mountains in the distance are covered in fresh snow and shine brightly. This haiku conveys the signs of spring and the harshness of the cold weather that tightens the body.

Are Kinome and Konome the same?

Although written with the same kanji, 木の芽, konome refers to the buds of trees in general. Read kinome, it refers only to the buds of Japanese pepper (山椒, sanshō).

In recent years, the two are often used interchangeably, but in the past they were used separately.

Is “Doll’s Festival” an event for girls?

March 3rd is the well-known as the Doll's Festival, or Hina Matsuri (ひな祭り). It is also called Joshi no Sekku (女子の節句)

In ancient China, there was a custom to purify oneself in the river on the Day of the Snake in early March. This is known as Jōshi no Sekku, ( 上巳の節句) and is believed to be the root of Hinamatsuri.

It is said that this festival was introduced to Japan during the Nara Period. Over time, Japanese began transferring their impurity to dolls made of paper or straw and then sending them adrift in a river (流し雛).

As time passed, these dolls began to be displayed on doll stands, and the festival evolved into the Doll's Festival.

March in the lunar calendar is also the season when peaches begin to bloom, which is why the other name Momo no Sekku (桃の節句, Peach Festival) was born.

Today, the Doll's Festival is as an event to pray for the healthy growth of girls. Until the Muromachi Period, however, it was a festival to pray for the health and safety of not only girls but also boys and adults.

Translated and abridged from Weather News.