Prison Break

Many children in Japan—the active ones, in particular—are amateur entomologists. Whenever they go out, they invariably return with bags and boxes and hands full of bugs. Today my family and I went to Mount Kizan (基山) in Saga Prefecture. No sooner had we got there than my wife and younger son started foraging through the tall grasses for insects. The hunt produced several grasshoppers and one huge preying mantis.

When we were leaving, the mantis caught one of the grasshoppers and bit its head off. It then proceeded to chomp the rest of its prey, save the wings and skinny forelegs. It is at the same time both disgusting and fascinating to watch a mantis in action, close up. Trust me on this. (Think Gladiator, only with exoskeletons and wings.) On our way home, my wife and sons fell asleep in the back seat. I was seated in the front seat, window open, elbow sticking out when I felt something crawling on my head. Then I heard what sounded like the fluttering of wings. At first, I suspected that a bug had flown into the car. It wasn’t until about fifteen minutes later when my wife woke up that I understood what had happened. “The mantis has escaped!!!” While my wife was asleep, her grip on the bag had weakened and the bug managed to crawl out. It then climbed up the back of my seat and onto the top of my head and flew out the window.

Unfortunately for the mantis it didn’t get very far. It rode for the next ten minutes on the top of our car, holding on for dear life.

The Challenge of Repatriating 6.5 Million people

"In the wake of defeat, approximately 6.5 million Japanese were stranded in Asia, Siberia, and the Pacific Ocean area. Roughly 3.5 million of them were soldiers and sailors. The remainder were civilians, including many women and children--a huge and generally forgotten cadre of middle-and-lower-class individuals who had been sent out to help develop the imperium. Some 2.6 million Japanese were in China at war's end, 1.1 million dispersed through Manchuria." (Dower: 1999, pp.48-49.)

I personally know (or rather knew, as many of them have since died) more than ten Japanese who were living abroad at the war's end. Their stories of repatriation are interesting ones.

My father-in-law was born on a ship that was returning to Japan a month before the surrender. I guess his parents had seen the writing on the wall and chose to get out of Dodge before things really turned really ugly. The Battle of Okinawa had finished only a few weeks earlier (June 22) so the waters between Taiwan and Kagoshima (where they were originally from) must have been crowded with Allied battle ships and aircraft carriers getting ready to mount an attack on the Japanese mainland. How their ship was able to pass safely is a mystery to me.

There were some 300,000 Japanese living on Taiwan, 90% of whom were expelled by April of 1946.

Another woman I know grew up in Taiwan. She was the daughter of a police officer on the island. The father of yet another woman was born in a small town on the southeastern coast of Taiwan. His family had been well-to-do, but lost everything when they left.

The father of a woman I know was a doctor in the Japanese Army in Manchuria. 1.6 to 1.7 million Japanese fell into Soviet hands "and it soon became clear that many were being used to help offest the great manpower losses the Soviet Union had experienced in the war as well as through the Stalinist purges." (Dower: 1999, p.52.) As a doctor, he was pretty much free to go were he liked and may have even had one of more Russian lovers during his time there. He remained in the USSR for I believe 8 years after the war. He was one of the few who did not want to be repatriated.

"From a logistical standpoint, the repatriation process was an impressive accomplishment. Between October 1, 1945 and December 31, 1946, over 5.1 million Japanese returned to their homeland on around two hundred Libert Ships and LSTs loaned by the American military, as well as on the battered remnants of their own once-proud fleet." (Dower: 1999, p.54.)

That answers a question I had about how so many people were able to return to Japan when four-fifths of all Japan’s ships had been destroyed. “The imperial navy had long since been demolished. Apart from a few thousand rickety planes held in reserve for suicide attacks, Japan’s air force—not only its aircraft, but its skilled pilot as well—had virtually cased to exist. Its merchant marine lay at the bottom of the ocean.” (Dower: 1999, p.43)

The Akasaka Prince Classic House was built in 1930 as the residence of Yi Un, the last crown prince of Korea. (旧李王家邸).

Tokyo's Chosen Ones

Strategic bombing, the military strategy employed in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale or its economic ability to produce and transport materiel, was used with a vengeance in the Pacific War. Sixty-six major cities in Japan had been bombed, “destroying 40 percent of these urban areas overall and rendering around 30 percent of their populations homeless,” writes John Dower in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Embracing Defeat. “In Tokyo, the largest metropolis, 65 percent of all residences were destroyed . . . The first American contingents to arrive in Japan . . . were invariably impressed, if not shocked, by the mile after mile of urban devastation . . . Russell Brines, the first foreign journalist to enter Tokyo, recorded that ‘everything had been flattened . . . Only thumbs stood up from the flatlands—chimneys of bathhouses, heavy house safes and an occasional stout building with heavy iron shutters.’” (Dower: 1999, pp. 45-46.)

Meiji Gakuin’s Memorial Hall (明治学院記念館) was built in 1890.

Having known of the extensive damage to Tokyo, it always perplexed me that certain buildings like those pictured here managed to remain, ostensibly unscathed by the bombings. Check out a satellite view of Tōkyō on GoogleMap and you’ll find many of these houses hidden like Fabergé Easter eggs in the urban sprawl of the metropolis.

As I was re-reading Dower’s masterpiece on Japan in the wake of WWII, I learned that it was no coincidence that these mansions were spared:

“Even amid such extensive vistas of destruction, however, the conquerors found strange evidence of the selectiveness of their bombing policies. Vast areas of poor people’s residences, small shops, and factories in the capital were gutted, for instance, but a good number of the homes of the wealthy in fashionable neighborhoods survived to house the occupation’s officer corps. Tokyo’s financial district, largely undamaged would soon become “little America,” home to MacArhur’s General Headquarters (GHC). Undamaged also was the building that housed much of the imperial military bureaucracy at war’s end. With a nice sense of irony, the victors subsequently appropriated this for their war crimes trials of top leaders.” (Dower: 1999, pp. 46-47.)

The former residence of Iwasaki Hisaya, an industrialist from the Meiji to Show periods (i.e. Mitsubishi Corporation), was constructed in 1896. It is located in Ikenohatai. (旧岩崎邸庭園)

Former residence of the Maeda family, built in 1929-30. Maeda was the 16th head of the Kaga Domain (present-day Ishikawa and Toyama prefectures). The Maeda rose to prominence as daimyō under the Tokugawa Shogunate and were second only to the Tokugawa Clan in regards to land value.

I have more photos of these buildings and houses which I will upload later.

Tatsuno Kingo’s Works

This painting of 45 of Tatsuno Kingō’s works, including The Bank of Japan (center) and Tōkyō Station (background) gives an idea what the Marunouchi area used to look like before the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, WWII, and the Great Wrecking Ball of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. For more on Marunouchi, go here.

According to Wiki, “Following the Meiji Restoration, Marunouchi came under control of the national government, which erected barracks and parade grounds for the army.

“Those moved in 1890, and Iwasaki Yanosuke, brother of the founder (and later the second leader) of Mitsubishi, purchased the land for 1.5 million yen. As the company developed the land, it came to be known as Mitsubishi-ga-hara (the "Mitsubishi Fields").

“Much of the land remains under the control of Mitsubishi Estate, and the headquarters of many companies in the Mitsubishi Group are in Marunouchi.

“The government of Tokyo constructed its headquarters on the site of the former Kōchi han in 1894. They moved it to the present Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building in Shinjuku in 1991, and the new Tokyo International Forum and Toyota Tsuho Corporation now stands on the site. Nearly a quarter of Japan's GDP is generated in this area.

“Tokyo Station opened in 1914, and the Marunouchi Building in 1923. Tokyo Station is reopened on 1 October 2012 after a 5 year refurbishment.”

Amami: What's Behind a Name

My mind has been on Okinawa a lot since returning from there a few weeks ago. If time permits, I'll try to write down some of my thoughts about the trip in the coming days and post some photos, as well.

The other day, I was talking to a doctor. Although he was born near Kagoshima city and has been living in Fukuoka prefecture ever since graduating from medical school, his family originally hailed from Amami Ôshima. He told me that unlike most Japanese whose family names are written with two or three (and occasionally four) Chinese characters (e.g. 田中 - Tanaka, 清水 - Shimizu, 西後 - Saigo, 坂本 - Sakamoto, 長谷川 - Hasegawa, 長曽我部 - Chôsokabe etc.), the family names of the people of Amami Ôshima are often written with a single character (e.g. 堺 - Sakae, 中 - Atari, 元 - Hajime).

This calls for a brief history lesson.

In the late sixteenth century, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (warrior and unifier of Japan 1537-1598) asked the Ryūkyū Kingdom for help in his ill-faited attempt to conquer Korea. Hideyoshi intended to take his ambitions on to China in the event that he succeeded in Korea, but as the Ryūkyū Kingdom was a tributary state of the Ming Dynasty, Hideyoshi’s request was turned down.

Having refused demands for aid on a number of occasions, the Ryūkyū Kingdom drew the ire of the newly established Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) and Shimazu clan of southern Kyūshū, and in 1609 the Satsuma feudal domain (present-day Kagoshima prefecture) was given permission to invade the kingdom. While the the Ryûkyû Kingdom was able to regain some autonomy a few years later, Amami Ôshima and other islands north of present-day Okinawa were incorporated into the Satsuma domain. (Incidentally, the islands had been independent before being conquered by the Ryūkyū Kingdom in 1571.) These islands remain part of Kagoshima prefecture to this day although the inhabitants are ethnically, culturally, and linguistically—you name it—closer to Okinawa.

A side note is worth mentioning here: "The islands, by virtue of climmate, were ideal for cane cultivation, and sugar was in high demand in Osaka. To increase revenue, the domain began to reverse its agricultural policy, discouraging the cultivation of rice in favor of sugarcane. In 1746 the domain began collecting all taxes in sugar. In 1777 it established a state monopoly on sugar, making private sales punishable by death. This emphasis on sugarcane led to the most brutal aspect of the island economy: widespread slavery and indentured servitude . . . Cane cultivation was labor-intensive, dangerous, and exhausting, and the most productive farmers were plantation owners who could mobilize scores of unfree workers. By the 1800s the island elite, the district chiefs and local officials, were all slaveholders. By the mid-1800s nearly a third of the populace were yanchu, the island term for chattel slave." (From Ravina, Mark. The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori. Hoboken: Wiley, 2004, p.83.)

As was the case for ordinary people in Japan proper, the people of Amami did not have family names until the islands came under the control of the Ryûkyû Kingdom. Family names may have been used in order to keep track of who was entering and leaving the kingdom. During the time that the islands were under the control of the Satsuma han (feudal domain), the residents were classified as farmers under the four occupations social class structure and not permitted to have names. The surnames that survive today were assigned after the fall of the feudal system and Meiji restoration in the late 1860s.

Now there was an exception to certain residents of Amami who had made great contributions to the Satsuma rule. These people, however, were given family names that consisted of one character. One purpose in doing so was to draw a distinction between people from Satsuma and those from the islands. Another reason was that as a tributary of China, the Ryūkyū Kingdom had used Chinese surnames (known as karana, 唐名. lit. “Chinese name”), and assigning such surnames was a way of acknowledging the historical connection to Ryūkyū. (Don’t quote me on this as I’m merely summarizing what others have written in Japanese.)

At the beginning of the Meiji era (1875), all Japanese citizens were required to have family names and the people of Amami tended to choose one-character names that they were familiar with. For a list of these names visit here.

People from outside of Kyūshū often comment that food, especially the soy sauce, is sweeter here than elsewhere. That sweetness is a vestige of those sugar cane plantations.

MakuJobbu

The other day I overheard a student of mine mention that she was a manager at the McDonald’s where she was working.

“A manager? Really?” I said. “But you’re only, what, eighteen?”

“I just turned nineteen.”

“How long have you been working there?”

She replied that it was her fourth year at the hamburger joint, that she had started in her first year of high school when she was fifteen, something that also surprised me as very few high schools allow their students to work. I know what you’re thinking, whose business is it whether a student has a part-time job or not? In Japan, the teachers tend to make it their business. They want their charges focused on little else than their studies. (We can discuss the wisdom of such rules later.)

“And how long have you been manager?” I asked.

“Only a few months.”

She went on to explain that of the sixty to seventy employees at her restaurant (if you can call a Mickey Dees one), there were fifteen managers, all of whom were “part-timers”. Part-timers in the Japanese sense of the word meaning that they are not full-fledged employees of the McDonald’s Japan Corporation with bennies rather than someone working less than thirty-two hours a week. This particular woman was currently working six days a week for a total of about thirty-four or so hours each week. During the summer break she put in over forty hours a week.

“How many ‘full-fledged employees’ (正社員, seishain) are there at your branch?”

“Just one, the store manager (店長, tenchō),” she answered.

I once knew a twenty-something-year-old woman who was one of these tenchōs. The sweetest, most unassuming woman you could ever meet, she was managing what was one of Japan’s busiest branches. It wasn’t unusual for her to remain at work until four in the morning, go home, sleep a few hours, then return the next morning to do it all over again. Her dream was to work at Hamburger University, a training facility run by McDonald’s Corporation, and for all I know, she may be working there now.

I continued to badger my student about the details of her work and learned that when she first started working she earned ¥700 ($6.70) an hour, but after a few months was bumped up to ¥720 ($6.90). As manager she now earns ¥750 ($7.19) an hour, considerably less than the $8-15 per hour an “hourly manager” can make in the States, but then she is able to keep 90% or more of her income due to the low level of taxation on part-time work here. Her counterpart in the U.S. might see some 30% of his income withheld in the form of payroll and other taxes.

As manager, she is responsible for overseeing the shift, training new employees, managing the money, and dealing with customer complaints.

“I like the job,” she told me, but admitted that the customers can be insufferably petty at times.

What took you so long?

“Why do you think you ended up staying so long in Japan?” Azami asks.

I have my pet theories; the top contender being this: to discover, à la Breakfast of Champions, how much a man can take before he ends up hanging himself.

“Hmm.”

“I think the reason you came to Japan,” she says, “was to meet me. Don’t you think so, too?”

Who knows? Maybe she is right. Then again, maybe she is wrong. Even if she were right, what would my coming to Japan have meant to all the other women I met along the way? Did I come to Japan to meet them, as well?

I give Azami a noncommittal shrug.

“You came here to meet me,” she continues with such confidence it’s hard to disagree. “Waited ten years, teaching all that time, so that you could learn what you really wanted and find the person you really needed.”

Well, at least she is convinced and that has to count for something, I suppose.

I’ve long had the gut feeling that existence is basically meaningless. No rhyme or reason to it all. But, humans being human can’t help trying to assign meaning and order to their otherwise chaotic, random lives and interpret life’s happenings with some kind of bias, be it religious, mythical, or philosophical. There is nothing wrong with that if it brings you closer to your “bliss”. A decade, though, is an awfully long time to look for someone, even someone like Azami.

“Ten years,” I say with an exaggerated grimace. “Why’d you make me wait so goddamn long?”

“Me?”

“Yeah, you. If we were meant to be together, why then didn’t you come around sooner, say, when you were still a freshman in high school? I wasn’t getting any younger, you know.”

My Oasis

The day is coming to an end.

The wind stills and the street below my balcony grows quiet.

A week has come and gone. Time passes too quickly.

One moment there is a phone call from a familiar voice and a visit by a woman I have come to love.

But, the next moment, I am saying good-bye, and am alone again,

My skin can feel it: time and love waits for no one.

I sometimes think that the only reason we have memories is that we might recall in bad times those times when we were happier. And with those memories, we are accoutred for our journey on,

Through the desert.

Small drops of water on a parched tongue.

I can get so thirsty at times.

But all I can do is press on,

One step at a time,

Each step sinking in the sand as I,

Search for the next oasis,

That is you.

Summer of Loathing

I don’t know of any other country where the destruction of war is as intricately woven into the fabric of the season as it is here in Japan. Throughout the estival months, documentaries and specials are broadcast on television and memorial services are held across the nation, reminding us of one needlessly tragic event in Japan's history after another.

The Battle of Okinawa began on April first and ended 82 bloody days later on the 21st of June. It was the largest, slowest, and bloodiest sea-land-air battle in American military history, claiming upwards of 250,000 lives (both military and civilian). My great uncle, Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., commanded the 10th Army, the main component of the expeditionary forces landing on Okinawa. On June 18th, just a few days before the end of hostilities on the island, he was struck down by enemy fire, becoming the highest-ranking U.S. military officer killed in World War II.[1] General Mitsuru Ushijima, Buckner's Japanese counterpart in the battle, committed ritual suicide on June 22nd by first disemboweling himself with a tantô (short sword) and having a subordinate behead him.

Last photo of Buckner (right) just before he was killed.

One of the more remarkable, and for many Westerners incomprehensible, features of the Battle of Okinawa were the kamikaze suicide attacks by Japanese pilots against Allied ships. Although they had been used in earlier military campaigns, the peak in kamikaze attacks came on the 6th of April, when nearly 1500 pilots took off from bases in Kyûshû never to return.

USS Bunker Hill after being hit twice by kamikaze.

Many Americans, I think, would be surprised to learn that most of the young men piloting these planes were among Japan's best and brightest, college graduates from the nation's top universities. One of these doomed kamikaze pilots was the older brother of an octogenarian student of mine who would himself go on to become a professor of genetics at Kyûshû University, studying at Yale and Princeton in the 50s and 60s. He can still be brought to tears when recalling the senseless death of his brother who, he says, had showed so much promise.

The ill-fated kamikaze attack coincides, incidentally, with the start of the swimming season at many beaches in Okinawa.

Months before the Battle of Okinawa had begun, the U.S. Air Force under the command of Curtis “Bombs Away” LeMay had been executing a massive bombing campaign against cities in Japan.[2]The most famous of these is the March 9-10th raid on Tôkyô when over three hundred low-flying B-29 Super Fortress bombers dropped cluster bombs armed with napalm on the city. The deadliest air raid of the war, it would destroy 16 square miles or a quarter of the city and kill more than 100,000 people.[3]

More raids were ordered: Nagoya (March 11/12th and again on the 14th and 16th), Ôsaka (March 13th) Kôbe (March 16/17th). LeMay intended to knock out every major industrial city in Japan in the next ten days, but ran out of bombs. Think about that.

In Errol Morris’s provocative documentary Fog of War, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara brings the numbing stats of the raids home:

“Why was it necessary to drop the nuclear bomb if LeMay was burning up Japan? And he went on from Tokyo to firebomb other cities. 58% of Yokohama. Yokohama is roughly the size of Cleveland. 58% of Cleveland destroyed. Tokyo is roughly the size of New York. 51% percent of New York destroyed. 99% of the equivalent of Chattanooga, which was Toyama. 40% of the equivalent of Los Angeles, which was Nagoya. This was all done before the dropping of the nuclear bomb, which by the way was dropped by LeMay's command.”

On the 19th of June, the city of Fukuoka, too, was bombed,[4] some 200 tons of incendiary bombs being dropped on the city.[5] The neighboring towns of Tôsu, Kurume, Moji, Shimonoseki, and so on were also attacked. The fact that these relatively minor cities were also bombed to kingdom come makes me wonder if any town was spared LeMay's wrath. If he had had his way, the whole country would have been left in ruins. "We don't pause," LeMay would write later, "to shed any tears for uncounted hordes of Japanese who lie charred in that acrid-smelling rubble. The smell of Pearl Harbor fires is too persistent in our nostrils."

The bombing of Fukuoka lasted for an hour and 42 minutes, destroying 3.77 square kilometers of the city and 33% of the buildings. 902 people were killed, another 586 seriously wounded, a small number when compared to the wholescale carnage inflicted upon Japan’s larger cities.

Reconnaissance photo of Fukuoka

Bombing of Fukuoka

Downtown Fukuoka (Tenjin) after the bombing.

Damage assessment.

I have found some conflicting accounts online--the numbers don’t quite add up--but apparently on the day after the air raid, eight airmen out of the twelve to twenty Allied POWs being held in Fukuoka at a detention center where the courthouse is located today were taken to the neighboring Fukuoka Municipal Girls' High School[6], where they were hacked with swords and beheaded. They were the lucky ones. Another eight had been trucked a few days earlier to the Kyûshû Imperial University Medical Department (today’s Kyûshû University) where they were used in a total of four vivisection experiments on May 17 (2 men), May 22 (2 men), May 25 (1 man) and June 2 (3 men).[7]There was another incident on Aburayama that involved more torture and beheading of POWs.

On July 16th, the first nuclear explosion was tested in America, proving that a nuclear bomb would work. Ten days later on July 26th, the US, Britain, and China issued the Potsdam Declaration which concluded with a “call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

That prompt and utter destruction came on August 6th when Hiroshima became the first city to have an atomic bomb dropped on it. Three days later, Nagasaki was also nuked. Both days are solemn ones of remembrance for the victims of the bombings, which claimed 150,000 to 246,000 lives.

Putting aside questions of the morality of dropping one, let alone two, atomic bombs on Japan after having already laid waste to most of the country with incendiaries, I have a problem with the bombings in that they allowed the Japanese to shift the focus of the discussion from one of remorse (look at the suffering we caused) to one of self-pity (look at how we suffered).

At noon on August 15th Emperor Hirohito read the Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the War effectively bringing the war to end. (What took you so long, Hiro?)[8] The date of Japan’s "surrender" happens to coincide with the final day of the Bon Festival of the Dead as it is observed in most of the country. This somber festival tends to signal the psychological end of summer in Japan, as I have written elsewhere.

I've always thought that making the 15th a national holiday--let's call it Heiwa no Hi (Peace Day)--would be an appropriate way to commemorate the end of the war. Most Japanese already have the day off anyways to attend to family business during the Bon holiday.

So there you have it: the Japanese summer begins in Okinawa at pretty much the same time that the battle for the island commenced and comes to and end with the surrender of Japan.

With all these gloomy milestones, it almost make me want to head back to the States this summer.

[1] A monument to General Buckner can be found at the place where he died atop a craggy knoll in Itoman City.

[2] American Experience produced an excellent documentary called “Victory in the Pacific” that can be viewed online at www.pbs.org

[3] Many dispute the number of casualties, arguing that the population density of the city at the time would have ensured even higher casualty figures.

[4] You can read the Air Objective folder here. Regarding targets in Fukuoka, it says, “The most important industries lie south of Kyushu University—a landmark on the Bay. The most southerly target is Nippon Rubber Co. TARGET 1265 producing footwear and a few tires. Large buildings in thie area which are not considered targets include the Tofu Flour Co., Dai Nippon Beer Co., and Kanegafuchi Spinning Mill. Fukuoka Harbor TARGET 1255 has been enlarged by a filled extension which is capable of taking on ocean-going ships. This made land is now covered with warehouses and has railroad connections with the Kyushu RR network. The new extension is the only known wharf on the Fukuoka side of the bay capable of taking deep-draft vessels . . .Southeast of the wharf is the old town of Hakata containing many small industries. The only large plant is Watanabe Iron Works, Plant No.1 TARGET 1238 which produces ordnance and heavy machinery for the Navy . . . North of the Najima River are the Najima Steam Power Plant TARGET 664 and the Najima Seaplane Base TARGET 1237. The power plant is connected with the same grid as the large Omuta steam plants and must be considered as a potential source of power for both the Omuta Region and the Nagasaki-Sasebo Region, as well as the Fukuoka industries. The seaplane base has declined in importance with the development of the Fukuoka Air Station TARGET 663 across the bay.”

[5] A detailed “War Journal” of the 9th Bombardment Group can be found here.

[6] Today, it is the location of Akasaka Elementary School, just three blocks from my home.

[7] Toshio Tôno, the founder of the OB/GYN where my first son happened to be born, was present during these vivisection experiments and wrote an eyewitness account of it called Ômei: Kyûdai Seitai Kaibô Jiken no Shinsô. Tôno, Toshio, Disgrace: The Truth of the Kyûshû University Vivisection Incident, Tôkyô: Bungei Shunshû, 1979.

One day when I went with my wife to Dr. Tôno's hospital, I found the book in the waiting room, there among the Japanese equivalent of Good Housekeeping and Parenting. What's this about, I wondered and started to read it. I couldn't put the book down. Dr. Tôno has devoted much of his life helping the families of the victims understand what happened and, hopefully, find closure. He was a good man who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Other books on this and related topics can be found here. A list of atrocities committed and punishments meted out by the occupying forces can be found here.

[8] About 2.7 million Japanese (servicemen and civilians) were dead by the end of the war, 3-4% of the country’s population of 74 million. One quarter of the country’s wealth had been destroyed, including four fifths of its ships, one-third of all industrial machine tools, and a quarter of its rolling stock and motor vehicles. Living standards fell to 65% of prewar levels. Sixty-six major cities had been heavily bombed, and 30% of the population of those cities were now homeless. Dower, John W., Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999, pp. 37 – 46.

The full transcript of the gyokuon hôsô (Imperial broadcast announcing the end of the war):

TO OUR GOOD AND LOYAL SUBJECTS:

After pondering deeply the general trends of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in Our Empire today, We have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure.

We have ordered Our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that Our Empire accepts the provisions of their Joint Declaration.

To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of all nations as well as the security and well-being of Our subjects is the solemn obligation which has been handed down by Our Imperial Ancestors and which lies close to Our heart.

Indeed, We declared war on America and Britain out of Our sincere desire to ensure Japan's self- preservation and the stabilization of East Asia, it being far from Our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement.

But now the war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone – the gallant fighting of the military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of Our servants of the State, and the devoted service of Our one hundred million people – the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest. (Understatement of the century.)

Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should We continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.

Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.

We cannot but express the deepest sense of regret to Our Allied nations of East Asia, who have consistently cooperated with the Empire towards the emancipation of East Asia.

The thought of those officers and men as well as others who have fallen in the fields of battle, those who died at their posts of duty, or those who met with untimely death and all their bereaved families, pains Our heart night and day.

The welfare of the wounded and the war-sufferers, and of those who have lost their homes and livelihood, are the objects of Our profound solicitude.

The hardships and sufferings to which Our nation is to be subjected hereafter will be certainly great. We are keenly aware of the inmost feelings of all of you, Our subjects. However, it is according to the dictates of time and fate that We have resolved to pave the way for a grand peace for all the generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is unsufferable.

Having been able to safeguard and maintain the structure of the Imperial State, We are always with you, Our good and loyal subjects, relying upon your sincerity and integrity.

Beware most strictly of any outbursts of emotion which may engender needless complications, or any fraternal contention and strike which may create confusion, lead you astray and cause you to lose the confidence of the world.

Let the entire nation continue as one family from generation to generation, ever firm in its faith in the imperishability of its sacred land, and mindful of its heavy burden of responsibility, and of the long road before it.

Unite your total strength, to be devoted to construction for the future. Cultivate the ways of rectitude, foster nobility of spirit, and work with resolution – so that you may enhance the innate glory of the Imperial State and keep pace with the progress of the world.

This is the full broadcast with the text translated into modern Japanese.

The Azaleas of Daikozen-ji

There really isn't a better time to visit Japan than the spring. During the first half of the year, a series of flowers bloom in a fashion as orderly as the Japanese themselves: narcissus and camellia in January; ume (plum) blossoms in February; peach blossoms and magnolias in March; sakura (cherry) blossoms in late March or early April, depending on the weather; wisteria, azaleas, and peonies around Golden Week (late April to early May); hydrangea from late May; irises in June, and so on.

Before coming to Japan I couldn't have identified a peony had my life depended upon it, but two decades on I'm practically a botanist. Much of my knowledge of the flora Japanica has come to me passively, through dating women who either taught, or were learning, ikebana (flower arrangement). The rest has been filled in by students, many of whom are invariably trotting off to, say, Mount Kuju to view the wild azaleas in June, foraging their local woods for horsetails and bamboo shoots in early spring, or joining tours to see a famous, centuries old sakura tree. (Seriously.)

I must be turning Japanese, because I too willingly (and gleefully) partake in these flower-viewing festivities. A few years ago I even traveled to the Daikôzen temple (大興善寺) in Kiyama, Saga prefecture just to see the azaleas (ツツジ, tsutsuji) there.

I need a life.

Cleaning Ladies

There’s 30 minutes left of class when nature calls. I consider holding it, but I know that if I do I’ll end up spending the last five minutes of the lesson squirming rather teaching. And besides the restrooms are only a few steps away. I could be there and back in less than 30 seconds.

So, I excuse myself . . .

Outside the restroom is a yellow slippery when wet sign and a cleaning lady’s cart. I pop in anyways only to find a youngish cleaning woman scrubbing down a urinal.

Pass!

If it were an old lady, I probably wouldn’t have been so shy, but . . . Well, you know.

So, I backpedal out the restroom and run down a flight of stairs to the fourth floor where I find another slippery when wet sign and another cleaning lady going about her business.

Curses!

Back out and down another flight of stairs and—dammit—another cleaning lady.

Second floor it's the same—This is getting fucking ridiculous—I jump in an elevator and go up to the sixth floor and, dammit, same deal. So, I hump up a flight of stairs to the seventh floor where—Praise the Lord!—there’s finally no cleaning lady and not a minute too soon.

The building at this uni is brand spanking new and spotless. After this morning’s game of cat and mouse, it’s no wonder why.

Keep up the good work, ladies, but please give me a heads up next time.

High Time for Summer Time

When I woke this morning, my bedroom was bathed in warm sunlight. It was not yet six in the morning and the sun was already peeking over the neighboring buildings and coming in through the windows.

“What a waste,” I thought as I crawled out of my futon.

Japan is not what I would call a morning country. Coffee shops and sports clubs don’t open until 7 or 8am at the earliest. Many of the better bakeries are still closed at 9:30am, and few restaurants bother to serve the most important meal of the day, breakfast. Contrast that with the US where you can work out at the gym from five in the morning and then promptly nullify the benefits of all that iron-pumping by gorging yourself on blueberry pancakes and bacon by six.

And yet, as the nation’s salarymen cover their heads with their pillows and try to sleep off their hangovers, the sun has been shining for two, three, and as many as four hours. This morning in Kyushu, for instance, the sun rose at 5:10am. In Tokyo, daybreak was at 4:27am. And, in Sapporo, dawn cracked at a remarkable 3:59am (around the summer solstice, sunrise comes as early as 3:30am): which begs the question: why doesn’t Japan have two time zones?

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. First thing’s first: Japan needs to re-adopt daylight-saving time (DST).

Re-adopt, you ask?

During the American occupation, Japan did observe DST for a spell, but abandoned it in 1951 when MacArthur left. For the average Japanese in those post-war years the extra hour of daylight in the evening equated to little more than an extra hour of labor.

But that was then and this is now.

With all fifty-four of the nation’s nuclear power plants idled indefinitely, Japan faces the daunting task of not only producing enough electricity, but also bringing consumption down during the summer months—precisely at the time when energy demand usually peaks. Failure to do so may lead to a repeat of the disruptive blackouts that plagued Japan last summer when the nation still had eleven nuclear reactors online. Daylight-saving time, specifically “double summer time,” may provide the answer.

While the energy-saving benefits of DST remain a contentious issue in the West, an interesting study conducted at the Toyohashi University of Technology by Wee-Kean Fong (Energy Savings Potential of the Summer Time Concept in Different Regions of Japan From the Perspective of Household Lighting; 2007) has shown that the implementation of a “split summer time”—whereby the southwestern half of the country moves its clocks an hour forward in April and the northeastern half of Japan, two—that is, double summer time—could provide considerable savings in energy consumption.

Were double summertime adopted, the Sapparo sun would rise at 5:59am and set at 9:05pm, providing plenty of sunlight when it is most needed. The benefits of DST, however, wouldn’t end there. According to the October 28, 2010 issue of The Economist, “adopting DST would mean a new dawn for the Japanese economy . . . boost[ing] domestic consumption, as people leave work for bars, restaurants, shopping and golf. Summer time is credited with reducing traffic accidents and crime; boosting energy efficiency as people use less lighting and heating; and even improving health as people are radiated with vitamin D.” The economic benefit, the article continues, could add as much as ¥1.2 trillion (USD $15 billion) to Japan’s GDP and generate 100,000 jobs.

Coming from America’s northwest where the sun sets as late as nine in the evening during the summer, I don’t need to be sold on the benefits of daylight-saving time. Summers, thanks to a simple biannual adjustment of the clock, have always been a time for late evening barbecues with family, twilight concerts in the parks, and relaxed meals at outdoor cafes with friends. The challenge, however, lies in convincing the average Japanese that, in addition to the conservation benefits of extra sunlight in the evening, DST could mean a better quality of life, not just more work.

Until then, all that beautiful sunlight will continue to go to be squandered. Mottai nai!

This was originally published in Metropolis, but the bastards removed my byline, so I have reclaimed it.

Oh, My Darlingu

The other day, I came across the results of a survey conducted by the Fujiya Company, maker of the long-selling milk-based taffy called Milky. According to the survey, the most common ways that Japanese women without children call their husband are:

By their name with -kun added, 31%

By a nickname, 29%

By their name without -kun or -san added, 14%

Another 11% call their husbands “o-Tō-san” (father) or “Papa”

The remaining 15% call their husbands in other ways

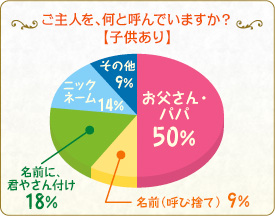

Once children are born, things change considerably:

The most popular way by far to call one’s husband is “o-Tō-san” (father) or “Papa”, at 50%.

The second most common way is by their name with -kun added, 18%.

Another 9% call their husbands by their given name, but without -kun or -san.14% call their man by a nickname.

And the remaining 9% call him in other ways.

I conducted a quick survey of my own with 16 first-year students between the ages of 18 and 24. The results were as follows:

I have written in the past about the different ways Japanese men refer to their wives. I will try to write about how they call their wives in the coming days and post it later.

Now, how do men call their wives in Japan?

If they haven’t got kids, 46% call their wife by her first name.

19% by her name plus -chan.

Another 19% by her nickname.

6% of “men” call their wife o-kā-san or mama (Ew)

10% in another way.

As we saw earlier, things change when children come into the picture:

39% now call their wife o-kā-san or mama.

22% by her first name alone.

13% by her name plus -chan.

9% by a nickname.

17% in another way.

One reason for the change is that once a child is born, everyone’s role in the family shifts, from wife to mother, from father to grandfather, and so on. People are often called in a way that reflects his/her relationship to the child. This is especially true when the first, or an older, child is a boy. He will be called o-nī-chan or o-nī-san (elder brother), even by his parents. A wife will call her husband o-tō-san or papa, her own parents o-bā-chan (Grandma) and o-jī-chan (Grandpa).

Although we use our first names in our family—my younger son seldom if ever calls his brother o-nī-chan (“big brother”)—my wife now calls her own mother, o-bā-chan.

Cosmetics maker Pola looked into this phenomenon and its unexpected, and perhaps unwanted, consequences.

Gotta Naraigoto

Ask a group of Japanese under the age of, say, thirty-five if they'd had lessons—what the Japanese call narai goto or o-keiko—when they were young, and you'll probably find most, if not all, did. Having been in the Eikaiwa (English conversation) trade for many years and having personally taught many preschool and elementary school aged children, I know from experience that Japanese children maintain schedules that would have American kids on their knees, crying, "Uncle!"

The whole business of training, cultivating, and educating children would be interesting to research some day. In the meantime, here are the results of a half-arsed survey I did the other day.

Of the twenty university sophomores (18♀/2♂) that I surveyed, 17 had had lessons of some kind before starting elementary school. By the time they had enrolled in elementary school, all of them were taking some kind of lesson. The most popular lessons were piano (15), swimming (13), calligraphy (11), and English and cram school, i.e. juku (10). Asked if they would also send their own children to these kinds of lessons, 19 said yes. The type and number of lessons they would like their children to take, however, changed.

I've long been interested in knowing not only what people studied and when, but also whether they feel they had benefitted from the lessons and whether they would do the same for their own children. Most, it appears, feel they did and would make their future children do likewise.

As a father myself the time will come soon enough when I will be forced to decide if I will make my own son take these kinds of lessons and what I will have him study. I am already leaning towards lessons in a third language, guitar, calligraphy, soccer, abacus, and swimming. The poor kid.

I originally wrote this blog post back in 2011 when my elder son was only a year old. Now that he is almost nine, I can say that the third language probably won’t happen until high school—getting the boys to be bilingual is hard work enough—musical lessons won’t happen unless they decide to pick something up themselves. Calligraphy? What was I thinking? That said, the older boy has nice handwriting thanks to his mother’s constant berating. The final three narai goto have worked out alright. The boys love soccer and have played on “teams” for several years now. Abacus, or soroban, can’t be more highly recommended. As for swimming, with their tight schedules it’s hard to put them in regular lessons, so we drop them off at intensive courses every long holiday. In addition to those, the boys have been doing karate two to four times a week. They also have English lessons with Daddy a few times a week.

Shh!! I'm recording!

How many of you out there remember holding a microphone up to the speaker and recording the radio onto a cassette tape? I do.

In 1983, cassettes tapes accounted for 47.8% of music sales; vinyl 44.6%. The jump in casette sales was a result of the debut of the Sony Walkman in the early '80s. Although CDs overtook cassettes in 1991, their sales peaked barely a decade later in 2003. Downloads overtook CDs in 2012.

In 2013, CDs accounted for 30.4% of all music sales. Downloads, meanwhile, accounted for 40% (singles, 22.4%; albums, 17.6%) Sales of ringtones peaked at 11% in 2008.

iTunes was released in January 2001; the iTunes Store in April 2003. The first iPhone was released in 2007.

When it comes to tech, I feel I was born at just the right time.

When I was young, we were riding rockets to the moon, exploring space. When I was in high school, the first personal computers were just starting to debut. In my first year of high school, I was typing reports on a clunky manual typewriter. Later, I was using an electric one that had all kinds of new-fangled gadgets like a correction tape. By my first year in college, the Mac was released, changing everything.

I experienced a range of cellphones and digital devices, such as “pocket bells”, simple digital cameras and electronic dictionaries, electronic notebooks, etc. Then Steve Jobs did a presentation of the first iPhone and a tech revolution followed that even the eggheads at Apple couldn’t have predicted.

Armstrong and Aldrin got from earth to the moon with only 4K of computing power. I now carry 64GB in my back pocket. Kids today probably can't imagine what it was like before computers and smartphones.

Unlimited

無限の可能性

Unlimited Possibilities

As I watch my boys grow, one of the things I often hear them say is “Daddy, I can now do this or that!” It doesn’t matter if it’s their studies or sports, they are constantly developing, maturing, getting better, learning, playing, mastering new things.

As I age, I find the opposite is true. There are things I can no longer do or, worse, things I think I am no longer capable of doing. Negativity is part of aging and to fight it I need to be more positive. Not in a silly Pollyannic way, but in a way that is rooted in reality. The possibilities may not be unlimited, but they are still there if you have an open mind and are willing to push yourself to try new things. Visiting this shrine in Kyōto reminded me of that.

Fifty, shmifty. I can do it.

Carpool Dad

At my son’s Tuesday evening soccer practice again.

It may sound silly to admit this, but I had no idea child-raising would be as time and labor intensive as it has been. For example, just getting the kids ready for school and kindergarten eats up a good two hours of my weekday mornings. (This should improve once they are going to the same school and are once again on the same schedule.) Then, there’s taking them to all their extracurricular activities and lessons and often having to hang around until they are finished—because in Japan you don’t just drop off and pick up; no, you’re expected to observe and then drill the kid later at home.

The evenings are occupied with making sure homework gets done and understood, providing the boys with opportunities to hear, read and speak English. Then there’s the feeding and cleaning up after them, getting them bathed and ready for bed, and finally reading book after book after book before succumbing to exhaustion and having to do it all over again.

Not that I’m complaining. I love watching my boys grow up, learn or master new things, overcome challenges. I wouldn’t give it up for the world. That said, I wouldn’t mind being able to sleep in every once in a while.

Fresh Coat

Went running around Fukuoka Castle to check on the cherry blossoms—not yet—and noticed that parts of the castle have been given a fresh coat of paint recently. Seems the city is finally putting some money into park maintenance. The arched bridge just below this yagura (turret) is also being rebuilt as is the iris garden.

I don’t think the city would have bothered if inbound tourism hadn’t exploded as it has these past few years.

Konpira Shrine

At the eastern entrance of Minami Kōen, a large, heavily forested park that is almost always deserted, you can find this small shrine dedicated to Konpira Gongen (金毘羅権現), god of merchant sailors. The shrine, which like the park is neglected by visitors, looks like something right out of a Miyazaki Hayao film.