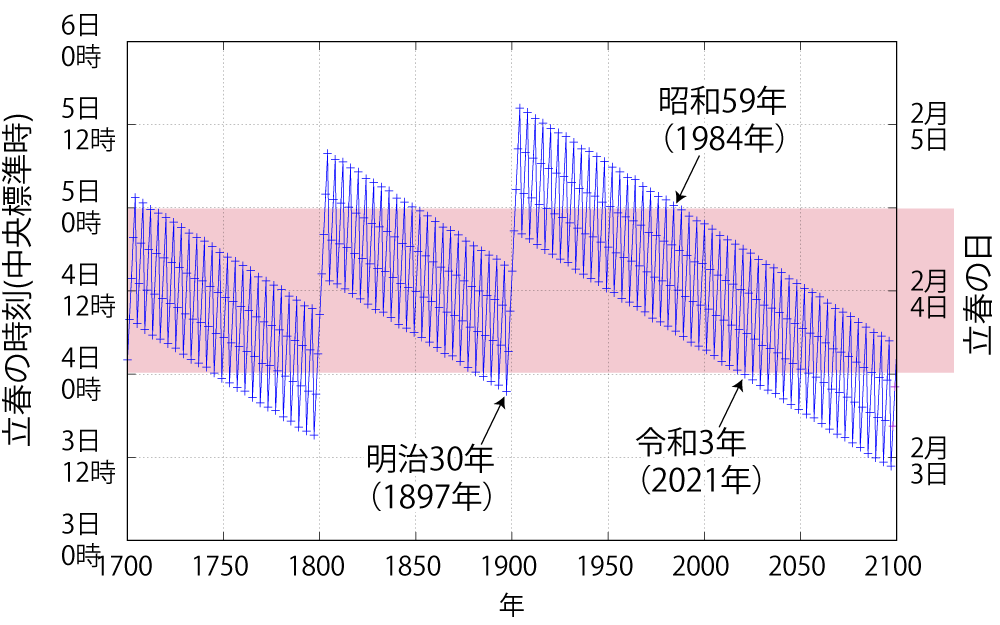

Next year, Setsubun will fall on February 2 for the first time in 124 years. This will also be the first time in 37 years that the seasonal ritual is not February 3rd.

For more, go here:

https://eco.mtk.nao.ac.jp/koyomi/topics/html/topics2021_2.html

Next year, Setsubun will fall on February 2 for the first time in 124 years. This will also be the first time in 37 years that the seasonal ritual is not February 3rd.

For more, go here:

https://eco.mtk.nao.ac.jp/koyomi/topics/html/topics2021_2.html

I was talking to a student about the draft in Japan during the war and how her grandfather had tried to enlist but was too short. Later on, of course, the Japanese military wasn’t very picky anymore and he got sent an akagami (lit. “Red paper) from the Imperial Army informing him that his time to fight had come.

He was still only 16 or 17 at the time and Americans were now at Japan’s doorstep. No longer too small to die for his country, he was trained how to unpin a grenade and lie down before an advancing tank to literally stop it in his tracks. Imagine that.

For some reason, that got me thinking about the Selective Service. I remember having to register at the age of 18 and for the next five years the potential to be drafted always hung over my head like an ominous cloud. Every time the US attacked or bombed another country—and we did it a lot during Reagan and Bush’s administrations, I always wondered if my own time to fight had come. It had only been a decade or so earlier that boys were being drafted to fight in Vietnam.

Fortunately for me and the soldiers who volunteer, the US military figured out that it was better in the long run to just pay service members more and improve the benefits package for veterans than to conscript unwilling citizens to do your bidding.

Out of curiosity, I went to the Selective Service’s website where I found a tool to look up your draft number. After some 30 years, I was still in the system. With a few clicks of the mouse, I printed out my Selective Service card. It would have come in handy when I tried to renew my license ten years ago and didn’t have a third piece of ID, such as my Social Security card, on me.

Although I was once a "Young Republican", today I consider myself a moderate Libertarian†. I can appreciate the need for Keynesian-style stimulus spending in times of recession and higher taxes to help reduce budget deficits, BUT nothing brings out my inner curmudgeon quite like seeing government money, my taxes, going to waste.

Two years ago I posed some questions for our newly elected mayor. One of them was: "Throughout Japan, and in Fukuoka, too, many historical spots are indicated by little more than concrete posts stating that this is the location that such and such happened. This is a missed opportunity to make the history live, to build authentic sightseeing spots. How can Fukuoka better highlight its historical heritage?" I also asked: "Many of the parks are poorly maintained. Gardeners come in only once every few months, hack at the weeds, trim limbs, and then leave the parks to be overrun with weeds, garbage, and the homeless once again. What can the city do to better maintain these areas, to make them places people would be happy to visit?"

Now, I'll be damned if in two short years the city didn't go on to address both of these issues head on. Maizuru Park where the ruins of Fukuoka Castle are located now has a regular crew of gardeners (most of whom are mentally retarded*) which tends to the flower boxes and generally keeps the park clean. And this visitor center located in the park was recently opened. Progress!

I have two problems with the center, though. One is the design which has nothing to do with Fukuoka Castle or the other structures in the area.

For instance, all of the restrooms in the park look like this:

White washed walls, known as shirakabe (白壁) with a gray border along the bottom half, reminiscent of townhouses in the Edo and Meiji eras.

Why didn't the city build a visitor center in this or a similar style, something that would have been both interesting for tourists to see and would have been in keeping with the previously established theme? The architectural style of this new building has nothing to do with the culture of Japan or Fukuoka. It's a missed opportunity, to say the least.

The second, and bigger, of the two problems with the visitor center is the price. How much do you think it cost?

Take a wild guess? Make it wilder . . . You're still cold. You're not even close, my friend.

The Fukuoka Jō Mukashi Tanbōkan ((福岡城むかし探訪館)) cost a whopping 70 to 80 million yen to build. (The Yomiuri Shimbun has the price at "about 70 million", and NHK reported recently that the center cost 78 million yen.) In dollars that comes to between $875,000 ~ $975,000. Almost a million bucks! And that is for the structure alone. The city didn't need to buy the land (usually the most expensive part of a structure) it was built upon. Imagine what your home would look like if you had put that much money into its construction. It would be fitted with saunas and Jacuzzis, heated floors, an elevator for your cars, a gorgeous designer kitchen, a wine cellar, living quarters for the help, and so on.

Obviously someone made a killing off of this little projects and it worries me to no end that the citizens of this city don't rise up and voice their disgust and anger. Instead, they just shrug.

The consumption tax is going to be doubled in a number of years, but as long as projects like these continue to waste money hand over fist Japan's massive public debt will never be addressed.

Your tax dollars at leisure.

Originally posted in 2012.

___________________________

†There is an excellent online tool which plots your opinions on political and economical matters on a "compass" and compares them with the policies and beliefs of political leaders, past and present.

Winston Churchill reportedly said, "If you aren't liberal at 20, you haven't got a heart; if you aren't conservative at 40, you haven't got a head." If that is true, then I was a heartless youth, and today at the age of 46 I am not sufficiently curmudgeonly for my age.

*By the way, you can holster your offense at my use of the word "retarded": one of my sisters was (she has already passed away), and two of my cousins are "mentally retarded". My sister’s case was so severe, she couldn’t say much more than “Ma-ma-ma-ma.” We all miss her.

This was originally written in March, 2012, a year after the Fukushima earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster.

It’s starting to sound like I do nothing but sit in front of the boob tube, but there was another one of Ikegami Akira’s television specials on Saturday night that is worth mentioning. Part of FujiTV’s series Ano Hi o, Wasurenai: Higashi Nihon Daishinsai kara 1 Nen (I’ll Never Forget That Day: A Year after the Tôhoku Earthquake and Tsunami), Ikegami’s program dealt with both the mechanism of the deadly quake and the energy crisis that has confronted Japan in its wake.

While last year’s tsunami was directly responsible for the shutdown of the Fukushima Dai’ichi nuclear power plant, subsequent, and might I add legitimate, concerns about the safety of nuclear energy have resulted in all but two of Japan’s 54 commercial nuclear reactors being idled[1]. The remaining two are also scheduled to be shut down soon[2], meaning that a country which once depended on nuclear energy to produce 31.4% of its electricity has had to make up the shortfall by importing more natural gas and coal precisely at a time when fresh tensions in the Middle East are driving fuel prices up.[3] Incidentally, 80% of Japan’s oil and 20% of its natural gas passes through the Strait of Hormuz, underscoring how crucial it is that Japan address its energy needs before another oil shock brings the country to her knees.[4]

Fortunately, Japan has options.

By sheer coincidence, I happened to be speaking to an engineer who had just come back from the Kyûshû Electric’s Hatchôbaru geothermal power plant located in central Ōita prefecture near the Asô-Kujû National Park. The largest of 17 geothermal power plants in Japan, Hatchôbaru along with the neighboring Ōdake geothermal power plant produces 122,500kW of electricity, which only amounts to about 1% of Kyûshû Electric’s capacity. The potential for geothermal energy in Japan, however, is great.

I may be oversimplifying this, but wherever volcanoes are found, a power plant can be set up using the steam generated by heat of the volcano’s magma. Japan, with its 119 active volcanoes—the third most numerous in the world—has the potential to produce some 23,470,000 kW of this clean energy. At present, though, Japan ranks 8th in the world in geothermal energy production, producing only 536,000 kW. What’s more Japan has not built a new geothermal power plant in over ten years. Only 0.3% of Japan’s electricity is currently being supplied by these geothermal plants. In spite of that, a surprising 70% of the word’s geothermal power plants are using turbines produced by Japanese companies, including Mitsubishi and Toshiba.

If Japan has the capacity and the technology, what then is preventing the country from taking advantage of this resource?

One, the initial costs can be quite high. Drilling the wells needed for a geothermal power plant costs several million dollars each (I’ve heard as much as five million dollars). And because the wells can only be used for about a year, as many as twenty wells may have to be drilled. The largest geothermal power plant in Iceland has 28 wells.

Two, the hot spring industry is against it. They worry that if the water is diverted for use in the production of electricity there won’t be any left for the spas Japanese love so well.

And, three, most of Japan’s volcanoes are located in National Parks which have strict regulations on development.

In February of this year, however, the Ministry of Environment has signaled that it is willing to consider opening up National Parks for the development of geothermal power. Officials from Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry have also been to Iceland to see how Japan might benefit by taking advantage of this natural resource, which has the potential of producing as much as 20 nuclear reactor’s worth of electricity.

Ikegami’s special also looked into Brazil’s biofuel industry. A similar system has already been adopted in Miyako-jima (Okinawa prefecture), where bi-products from shôchû and sugar production are being used for bio-fuels and the fiber from sugar canes is burned to produce electricity. The aim is to make the island completely energy-self sufficient.

Other towns in Japan have also taken the initiative, including one farming village in the Tōhoku region—the name escapes me right now—which currently produces enough energy from biomass and other sources that it is able to sell its excess electricity back to the power company.

While Japan may not realistically be able to do without nuclear power in the short-term—the demand for electricity, particularly in the summer is still too great—I do think there are things that the country can start doing today to encourage the use and production of alternative energy sources. I’ll address this issue in a day or two. (For more on this, go here.)

[1] According to a recent poll by Tôkyô Shimbun, 80% of Japanese asked were in favor of phasing out nuclear energy.

[2] By law, nuclear reactors in Japan must be idled every 13 months in order for safety checks to be conducted. Once shut down, however, public pressure has prevented them from being put back online.

[3] Before the earthquake, Japan got 31.4% of its electricity from nuclear power plants, 60.3% from thermal power plants, 8.1% from hydropower, and 0.5% from renewables such as wind and solar. Today, 7.3% of electricity is generated by nuclear power plants, 86.3% by thermal power plants, 6.1% by dams, and 0.6 by renewables. (Note: these figures are for 2011-2012.)

[4] That Japan had the infrastructure in place to compensate for a loss of over 23% of its nuclear power capacity is truly amazing. I don’t think America would be able to make up the loss.

Bud Clark, future Mayor of Portland, OR, in the iconic “Expose Yourself” to Art Poster

On Sunday evening we received an email from the kids’ school informing us that one of the cooks in the kitchen had contracted COVID-19. (Uh-oh.) The school assured us parents that the person in question had had no contact with teachers or students. It also said that the remaining cooking staff had been sent home to quarantine for two weeks. What’s more, professional cleaners had been brought in to disinfect the kitchen and related areas over the weekend. As a result of the steps that had been taken, kids would be able to go to school on Monday with only one change: there would be no apple jam in Monday’s school lunch as the infected person had been in charge of it.

I asked my wife why the school would even bother mentioning the jam.

“Because some petty-minded parent would complain,” she replied. “There was no apple jam in my child’s school lunch!”

True. True.

Now, I wouldn’t say we were on pins and needles about this, but still I was checking my email every now and again to see if a cluster would develop at the school.

Well, late Monday night, we got another email from the school. Fortunately it was about a different kind of exposure.

“What is it,” my wife asked, her voice tense.

Just another pervert, I answered.

“Oh, what a relief!”

For a very limited time Rokuban: Too Close to the Sun is available for free downloading. Get it! Read it! Love it! Share it! Review it!

The other day, I was talking to some students about my high school's annual food drive when I explained that we boys would go canvassing for canned veggies and . . . they all gave me an odd, quizzical look.

Canned vegetables? What are canned vegetables.

So, I googled it and showed them some photos of the kind of thing I was talking about. It was only then that it dawned on me that after all these years in Japan, I don't think I have eaten many vegetables that weren't fresh and/or in season.

Take spinach. Yes, please take it.

Growing up in 'Merica, spinach was a common side dish on many dinner plates, but I don't think I ever saw raw spinach until I came here. It had always been canned or frozen when I was a kid.

Another staple veggie is peas and carrots. I've never had this here. And I thank my lucky stars because of it.

Now, I often grumble that the selection of fruits and vegetables at my local supermarket leaves much to be desired. (I was looking at a wimpy, woebegone pomegranate at the supermarket yesterday that was selling for almost ten bucks and thought nope.) But, what you can find here is fresh, usually locally grown, and of high quality. If only I could find a lime that didn't cost two bucks.

Looks awful.

Some 15 years ago, my wife and I visited this temple deep in the mountains of Itoshima. We were the only visitors at the time and felt honored when the Buddhist priest on duty invited us into the Holy of Holies or Apse, so to speak, to give us an up-close view of the 1000-handed Kannon statue. As we knelt before it, he burnt incense and chanted a lengthy sutra.

It had been a hard year, but at the time things were looking up. Being prayed over, I couldn’t help feeling that we were experiencing a spiritual spring cleaning that swept all of the negativity of the past several months away. And when it was finished and we stepped down from the we emerged that sacred space, I felt as if a heavy burden I had been carrying had become lighter.

As we left, toes frostbite from the cold, but hearts warmed and filled with hope, I suggested coming again the following year. And we did, year after year until our first son was born and child rearing became all-consuming.

In the meantime, Japan changed. The world changed. There was no SNS or smartphones when we first visited. There were few inbound tourists, too.

Now, I don’t want to sound like a crusty old fart, but I prefer how things were then—little known, quiet, special . . . holy. Thanks to COVID-19, the crowds that had beeb overwhelming so many places known for their tranquil and sublime beauty are once again worth visiting. (That was how I felt when we visited Dazaifu last week, too.)

We may have missed the peak of Sennyoji’s autumnal beauty this time by a few days. But I couldn’t have been happier to see the temple as I remembered it.

And as we left, I suggested once again that we try to come again next year.

From Wiki:

Sennyo-ji (千如寺) is a Shingon temple in Itoshima, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan. Its honorary sangō prefix is Sennyo-ji Daihiō-in (千如寺大悲王院). It is also referred to as Raizan Kannon (雷山観音).

According to the legend, Sennyo-ji was founded in the Nara period by Seiga, who came from India as a priest during the period.

Due to its position in the north overlooking the Sea of Genkai, it has been expected from the shogunate as a prayer temple of the foremost line against the Mongol invasions of Japan during the Kamakura period. In its heyday has been said to be lined up to 300 priest living quarters around the temple. Sennyo-ji is a general term of this temple, and it is also referred to as the priest's lodge that was located next to the middle sanctuary, the present day site of Ikazuchi-jinja. The wooden Avalokiteśvara statue is the subject of mountainous faith that has been enshrined in the main hall.

During yesterday morning's walk an attractive woman with relatively large breasts passed by.

”You think they're real?” my wife asked.

The smart answer would have been: Huh? But, no, I said, "Yeah, I think they are the way they jiggled like jello."

"So you were looking . . ."

"Last time I checked . . .," I dug my hand deep into my pocket and fiddled around, "yup, I am still a man. What do you expect? I see something jiggling like in the corner of my eye and I'm going to peek. I have no control over this. That's how guy's are wired."

"Hmm. So, what's more important to you—face or boobs."

"Face. Definitely the face. But, when I'm walking around town, I'll probably notice the figure, the breasts first. So, I'll check out the woman's breasts first, then look at her face, then back at her breasts, then, I guess I'll have a look at her ass . . ."

"You've got a whole system, haven't you?"

"I do try to be efficient in all things I do."

"If you're so attracted to large breasts . . ."

"Those weren't that large. But they were good size. Just the right size. You don't want a woman with watermelons or even cantaloupes. Navel oranges are nice. So is the occasional grapefruit, but never an amanatsu."

"Are you a greengrocer?"

"No, I'm just saying big, relatively big, is nice, but too big is just going to cause you trouble down the road."

"Say you have to choose between a beautiful woman and one with large breasts . . ."

"The beautiful one, of course."

"Why?"

"I don't want to have ugly kids. That woman's face may end up on my offspring . . ."

"So it's instinct."

"Probably. The same is true with tall women. I like tall, slender, athletic women . . . Well, like you."

"Okay. So face over boobs?"

"Definitely!"

"How 'bout boobs over height? A tall, slender woman with no boobs or a short woman with nice breasts."

That gave me pause for thought. I'd had both over the years and liked both. Preferred taller women, yes, but, breasts . . . There was that one girl who was quite adorable. She was really short, but had . . . Hmm . . . She was a lot of fun, though. But then there's something about walking around town with a tall, slim good-looking woman. Everyone's head turns . . . Hmm . . .

I must have walked over a block when my wife finally said, "You're really thinking about it, aren't you? I don't think I've ever seen you so lost in thought. You're the worst."

I took my son, Yu-kun. to kindergarten this morning (by means of Mama-chari) and managed to arrive at the very same time as one of the school busses.

The kids all clamored out of the bus and were herded by two teacher to the main gate of the school where they put their hands together, bowed deeply, and shouted in unison: "Hotoke-sama, ohayō-gozaimasu! Enchō-sensei, ohayō-gozaimasu!" (Good morning, Buddha! Good morning, Mr. Principal!)

It was my first time to see this, and I must say it was quite adorable.

Yu-kun also takes the school bus from time to time depending on the weather and my wife's energy level. (He rode it yesterday but ended up vomiting all over himself and had to be sent back home.)

The “pink bus”[1] usually doesn’t come rolling into our neighborhood until a few minutes after nine in the morning (which is why we often just drop him off ourselves around eight).

When the bus comes to a full stop, one of the teachers hops out, grabs the kids and tosses them in like sacks of recyclables. Once on board, the kids are free to sit wherever they like. Yu-kun sometimes sits in the very front next to the driver, sometimes in the middle near a girl he has a crush on, and sometimes in the very back like yesterday (which may be the reason why he threw up).

The kids are usually dressed in a variety of uniforms. Some wear the whole get-up with the silly Good Ship Lollypop hats and all, while others wear their colored class caps. Some are in their play clothes, a few in smocks, and fewer still wear their school blazers. Anything goes really and that’s fine by us.

A year and a half ago, my wife and I were considering four different kindergartens. Two were Christian, one Buddhist, and a fourth was run by what appeared to be remnants of the Japanese Imperial Army’s South Pacific Division.

It was this fourth kindergarten that initially appealed to us. The kids were said to be drilled daily and given lots of chances to exercise and play sports outside, something that offered us the possibility that our son would come home every afternoon dead tired.

Well, in the end, that school didn’t want us. (So, to the hell with them!) We went for the free-for-all Buddhist kindy, instead.

I think we made the right, albeit expensive, choice.

The other morning, I happened to see the bus for the Fascist kindergarten. Although it pulls up at the very same place where Yu-kun usually catches his own bus, the similarity stopped there. For one, all the kids were wearing the same outfit with the same hats, the same thermoses hanging from their left side. When they got in the bus, they did so in an orderly fashion, the first child going all the way to the back, the second child following after and sitting in the next seat. The bus was filled from the back to the front and I wouldn’t be surprised if the children filed out of the bus in the same orderly manner. Once seated, the kids sat quietly. It was at the same time both impressive and horrifying.

[1] I still have no idea why it is called the “pink bus” because nothing on it is pink. Every time Yu-kun says, “Oh, the pink bus!” I scan it from bumper to bumper to try and figure out how on earth he can tell it’s the pink bus and not the “yellow bus” which is actually yellow.

The Buddhist kindergarten is popular with parents who are doctors. I once asked a mother why and she replied that she wanted her children to just play and play and play before they had to knuckle down and start cramming from elementary school for their entrance exams. Poor kids.

A few years ago, I had the girls in one of my classes make mini presentations, the purpose of which was to learn how to present data. One student gave a short presentation on how the typical Japanese student spent her money. It contained some surprises.

As you can see from her pie chart above, the two largest expenses are social (drinking, dating, hanging out with friends) and food. The third largest expense was clothing and beauty products. What struck me as odd was that rent accounted for only 4% of their expenses, the same as what they were spending on their phone bill.

I'm not sure how the data was collected or who conducted the survey, but I assume that the reason rent does not amount to very much is because the average student even if he is living alone does not pay for his own rent. His parents do. Such is the rough life of the typical student in Japan. (Best of all, they don’t really have to study, either.)

My own college experience couldn't have been more different.

In my second year of college, three of my friends and I shared a two-bedroom two-bath apartment in the tony neighborhood of La Jolla just north of San Diego. The rent was $800, which came to $200 each. (Peanuts today when you consider that rents in La Jolla Village are way over $4000 today.) At the time I had a "part-time" job, working 32-plus hours a week (M-Th, swing shift, and occasionally the graveyard shift as well) at the La Jolla Cove Hotel, a real dive, that paid about four bucks an hour. I took home around a hundred dollars a week after withholdings, half of which was gobbled up by rent. The remaining half had to somehow cover all my extra expenses. It was no day at the beach, let me tell you.

According to the Department of Industrial Relations, the minimum wage in California in the early 80s was $3.35 an hour. In 1988, it was raised to $4.25.

I remember taking the job, one, because of the location--it was just a few blocks down the street from the apartment--and, two, because I thought the pay and work schedule were pretty good.

One of the interesting things about the job was that in an age when computers were starting to take off, the hotel continued to do everything in completely analog fashion. For instance, we had several large boards, measuring about a two and a half feet by two feet on which all the bookings were recorded. If someone called to reserve a room we would first have to ask when and how long the guest intended to stay and in what kind of room. The usual questions, right? But, then we would have to go over these boards and see if there was an availabilty. It would sometimes take five minutes just to confirm whether a room was available or not. If we had a room and the price was right, the guest would reserve it, which consisted of my physically writing down the guest's name on the board. Surprisingly, there weren't many mistakes. Guests weren't always happy with the room they got, but we seldom forgot a reservation.

4% for rent. Sheesh. What I would have done to pay $16 to cover rent in those days.

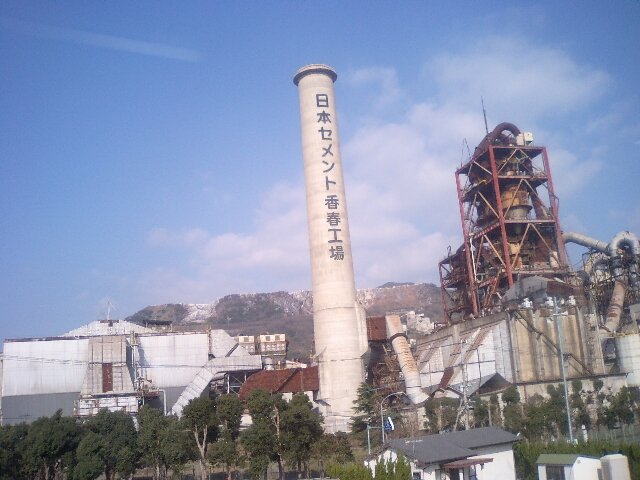

Above is what Mount Kawara (香春岳) of Tagawa City (田川市) used to look like before Nihon Cement (now Taiheiyō Cement) shaved layer after layer off the top trying to get at its limestone.

When I first visited Tagawa some twenty years ago, the right half of Kawara-dake had already been stripped down to about a third its original height, leaving a sheer cliff of stark white limestone on the left.

Today that has also been mined. Now that's progress!

What do women want in a prospective partner? Well, that depends on which generation you ask.

During the bubble years in Japan, women were said to be looking for the “Three Highs” in men (3高): Height (高身長), High income (高収入), and High education (高学歴). (It was also preferable if the man was not the first-born son due to all the incumbent responsibilities.)

In the ‘90s, the “Three Cs” were sought after: Comfortable (annual income over ¥7m), Communicative, and Cooperative (i.e. someone who helped around the house).

In the 2000s, the “Four Lows” were popular with women (3低): Low Posture (低姿勢, humble), Low Dependency (低依存), Low Risk (底リスク), and Low Maintenance (低燃費).

Today, modern Japanese women are said to be looking for the “Three Warms” (3温): Kindness, Affection and Peace of Mind. As for the Three Highs of the bubble years, Height now ranks 7th, High Income ranks 10th, and Income is 19th.

Your thoughts?

It’s not uncommon for students at the private Baptist university where I teach to have transferred from more prestigious schools.

Two years ago, I had a freshman who was in his late twenties. When I asked what had happened, he explained that he had dropped out of Tōkyō University—Japan’s equivalent of Harvard, MIT, CalTech combined—several years earlier. Girl trouble he confessed with a shrug. Another student who ended up auditing my classes more than four times admitted with a maniacal laugh that he had been kicked out of Keio University, Japan’s oldest institution of higher learning. “I may get kicked out of this school, too,” he added with more nervous laughter.

Hiroshi’s case, however, was something of a novelty. The strapping freshman had been a student at Bōei Dai (防衛大), the National Defense Academy of Japan a year earlier. Similar to West Point, Bōei Dai is a four-year military academy for those who wish to serve as officers in Japan’s military, er, Self-Defense Forces.

“It was like hell,” he told me and went on to describe the rampant hazing and bullying by upper classmen. “Fifteen of my classmates quit after only three days. Three days!”

“How long did you last?”

“One semester.”

He added that of the more than five hundred freshman who are accepted to Bōei Dai, only three hundred or so make it all the way through to graduation. A former graduate of the university wrote that out of the 530 or so students who entered Bōei Dai when he did, only 450 made it all the way to graduation. Most quit within the first week or so.

High drop-out rates are not unique to Bōei Dai. According to a New York Times article from 1985, West Point, too, has a high level of attrition.

“Through it all, the number of dropouts at West Point remains high," the article states. "Last year's graduating class of 986 officers began with 1,462 plebes, an attrition rate of 33 percent. It has been as low as 28 percent and as high as 40 percent. The academy considers 20 percent the minimum it should expect.” (The Baltimore Sun painted a similar picture of the situation at The U.S. Naval Academy.)

“It took forever to get anywhere on campus,” Hiroshi recalled. “Anytime you came upon a teacher or upper classman you had to stop and salute and wait until they passed. Walk three steps, stop and salute. Walk three steps, stop and salute. Walk three steps, stop and salute. It was bullshit.”

While Hiroshi was still a university student, he entered an extracurricular military school where he trained on weekends and during the long breaks, similar to the reserves, I guess. He also sported a buzz job, which made him stand out on campus even more. Well, I’m happy to say that all the hard work and perseverance has paid off because Hiroshi is now a paratrooper. When he graduated from ranger school, he commented on Facebook that had finally recovered his dignity.

Hiroshi’s a remarkable young man and I wish him all the best.

Proportion of atheists and agnostics around the world.

Several years ago, one of my many nephews posted the following quote to his Facebook profile:

Let me tell you, that really pissed me off. But, rather than admonish him for being so damn ignorant, I let it slide. What would the point be? At the age of eighteen he already had such strong beliefs in his Christianity that he would have been impervious to anything I had to say.

The boy had a reason for being cocksure: he had just been admitted to the U.S. Naval Academy. He would by and by graduate with honors and get accepted to the Top Gun fighter pilot training program, his childhood dream. The kid, no slacker, was certainly bright. Nevertheless, he was still capable of being dumb.

When you have as many brothers and sisters as I do—there are thirteen of us (Bloody Catholics!)—there’s bound to be differences in opinion about politics and religion. My siblings fall into a number of camps politically: there are liberals, moderates, like myself, kooky libertarians, and way-out there conservatives. There are born-again Christians, devout Catholics, salad-bar Catholics, Agnostics, Freethinkers, and the token salad-bar Buddhist: me.

My nephew, needless to say, aligns himself with the conservative born-again Christian camp of the family. His mother, an older sister of mine, home-schooled many of her children, and none of them have fallen far from the tree. They are for the most part aliens to me. Whenever I have the rare chance of talking to them—We met in person for the first time in 18 years a three summers ago—I honestly don’t know what to say. It’s like tiptoeing through a landmine. Now, I’m not saying that they are obnoxious, because they aren’t. They’re extremely decent and polite. All of them are very good-looking, too. It’s just that they have such firm beliefs about everything you know you’re going to end up disagreeing. And afterwards, they’ll pray for you: “Poor uncle has strayed from the path, O Lord. Please help him see the light.” Or some kind of crap like that.

I just checked my nephew’s Facebook profile and saw that the quote remains, indicating to me that he must really believe it.

Atheism is the opiate of the morally degenerate.

What a quote. Obviously, someone thought they were being clever by corrupting the oft-quoted paraphrase of what Karl Marx had written: “Die Religion . . . ist das Opium des Volkes.”[1]

What irked me so much about the quote was the bold assertion that Atheists were immoral and that only those who believed in God—the Christian Gawd, mind you—were morally upstanding.

As you might suspect, I disagreed.

First of all, you’re not a truly moral person if the only reason you do good or shun “evil” acts is to avoid punishment in the afterlife or be rewarded with a passage through the Pearly Gates. A lot of Christians fail to understand that this is a very low-level, if not childish, stage in moral development. No, a truly moral person does good because it is the right thing to do. He follows standards of morality that are universal, that apply to all people at all times. Do not kill. Do not cheat. Do not steal. Do not lie. Do not hurt others. Why? Because we’re all in the same goddamn boat here and life is difficult enough as is to be made even more difficult by inconsiderate arses.

Now, I’m not saying people who do good only so that they might go to Heaven are bad. If that’s what works for them, and if their beliefs enable them to function as good citizens, then the more power to them.

The problem is that many self-confessed “good Christians” are not very good at being true Christians, that is, loving, kind, understanding and accepting, open-hearted, giving, concerned about the less fortunate, forgiving, and so on. No, far too many “good Christians” are hating, unfriendly, unaccepting those different from themselves, close-minded, callous towards those less fortunate, judgmental, and downright mean.

They are also dishonest.

In Japan, in this den of morally degenerate Atheists, I can leave my notebook computer, iPhone, and wallet on the table at a café while I pop into the restroom and expect to find everything untouched when I return. In America, all three would be gone before I could even unzip my fly.

A decade ago while we were waiting in line at the check-in counter at the airport, my father dropped his money clip. The clip contained quite a bit of cash, his driver’s license, and some credit cards.

After I checked in and was heading towards the departure gate, I could hear my father’s name being paged over the airport PA system: “Mr. Crowe, please return to the United check-in counter.”

Back at the check-in counter, the ground staff handed my father his money clip, saying, “I believe you dropped this.”

Returned was my father’s money clip, his credit cards and driver’s license, but no cash. My suspicion is that the Naval officer who had been standing right behind us in line noticed my father drop it and, thinking this was his lucky day, had pocketed the cash. Thank you for your service, indeed!

In that God-fearing country, America, finders truly are keepers, and losers weepers. I often joke that would be a far more fitting motto than E pluribus unum.

Meanwhile in Godless Japan, you can be pretty sure—not 100%, but pretty damn close—that when you lose or forget something, you’ll get it back.

According to a recent article published in Rocket News, “In 2014 alone, a stunning amount of cash and lost possessions was turned into police stations around Tokyo. In cash alone, over 3.3 billion yen was turned in. That’s a whopping US$27.8 million picked up and taken to the authorities. Could that happen anywhere else in the world?”

Probably not.

Incidentally, I once left my notebook computer at an ATM. A brand-new MacBook Pro with all the bells and whistles, worth about three thousand dollars, I didn’t realize I had forgotten it till I was on the other side of town. I hurried back to the ATM, and—God bless the moral Atheist—it was still there. In the half hour or so that had passed, I’m sure several dozen people must have used the ATM and seen what was obviously a case holding a notebook computer, and yet no one took it.

David Sedaris made an interesting observation about Japan in his book When You are Engulfed in Flames:

“You don’t put your dirty shoes on the seat like many Americans do because, one, people sit there, two, it’s disgusting, and, three, you might stain a person’s clothes if you do. You wouldn’t like to sit down on a dirty seat would you? You wouldn’t like another person’s inconsideration cause your new dress to get dirty, would you?”

There is a basic consideration for others here in Japan, a desire not to inconvenience the people around you that is a much better driver of moral behavior than Heaven or Hell ever could be. I’ve said it before, but Americans could learn a lot from the Japanese in this regard.

Incidentally, my quotes include:

In the beginning of a change, the patriot is a scarce man, and brave, and hated and scorned. When his cause succeeds, the timid join him, for then it costs nothing to be a patriot—Mark Twain, Notebook, 1935

El día que la mierda tenga algún valor, los pobres nacerán sin culo./The day shit has value, the poor will be born without arses—Gabriel García Márquez

I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don't let anybody tell you different—Vonnegut, Timequake

Ultimately, literature is nothing but carpentry. With both you are working with reality, a material just as hard as wood—Gabriel García Márquez

縁なき衆生渡し難し (Even Buddha cannot redeem those who do not believe in him)

Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them—Thoreau

Feather-footed through the plashy fen passes the questing vole—Evelyn Waugh

Everything about woman is a riddle, and everything about woman has a single solution: that is, pregnancy—Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra

“The world must be all fucked up,” he said then, “when men travel first class and literature goes as freight.”—Gabriel García Márquez again

Amputees suffer pains, cramps, itches in the leg that is no longer there. That is how she felt without him, feeling his presence where he no longer was— Gabriel García Márquez, Love in the Time of Cholera

We must question the story logic of having an all-knowing all-powerful God, who creates faulty Humans, and then blames them for his own mistakes—Gene Roddenberry

It is better to spend money like there’s no tomorrow than to spend tonight like there’s no money—P. J. O’Rourke

[1] The full quote rendered into English is “The full quote from Karl Marx translates as: “The foundation of irreligious criticism is: Man makes religion, religion does not make man. Religion is, indeed, the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet won through to himself, or has already lost himself again. But man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man – state, society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world. Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopaedic compendium, its logic in popular form, its spiritual point d’honneur, its enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, and its universal basis of consolation and justification. It is the fantastic realization of the human essence since the human essence has not acquired any true reality. The struggle against religion is, therefore, indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion.

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

Despite consistently ranking as one of best cities in the world to live, shop, or eat, Fukuoka also has a reputation among the Japanese as being one of the wildest, most dangerous places in the entire country. Because of its reputation for violence and crime, the prefecture has been called “Ashura no Koku” (阿修羅の国).[1]

So, why the bad rap?

For one, Fukuoka prefecture often tops the country in number of shootings and bombings with hand grenades—yes, that’s hand grenades. The prefecture also has the ignominy of being a leader in accidents caused by drunk drivers. The rate of burglary is high, as is the total number, and the rate, of sex crimes, and so on.[2]

The cause of the high level of crime has been attributed to the large number of organized crime syndicates operating in the prefecture, its proximity to the Sea of Japan, which is said to facilitate smuggling and exile, and tougher anticrime measures in Kantō and Kansai.

[1] Ashura in Buddhism is the name of the lowest ranking deities of the Kāmadhātu (Buddhist cosmology). They are described as having three heads with three faces and four to six arms. The state of an Asura reflects the mental state of a human being obsessed with ego, force and violence, always looking for an excuse to get into a fight, angry with everyone and unable to maintain calm or solve problems peacefully. (Wikipedia)

[2] *Fukuoka also has the highest rate in Japan of unmarried women in their 20s and 30s. This is supposed to be a “bad thing”, but personally, I believe it adds to the city's livability.

1(1) 粕屋町 216.36(250.42)(福岡地方)

2(5) 田川市 206.87(175.84)(筑豊地方)

3(4) 苅田町 194.41(178.84)(北九州地方)

4(6) 福岡市 179.13(174.12)(福岡地方)

5(10)志免町179.05(164.50)(福岡地方)

6(9) 川崎町 176.34(165.01)(筑豊地方)

7(8) 直方市 175.73(168.34)(筑豊地方)

8(3) 飯塚市 171.02(187.60)(筑豊地方)

9(33)赤村 165.94(115.05)(筑豊地方)

10(24)古賀市163.81(132.98)(福岡地方)

11(14)水巻町161.25(144.69)(北九州地方)

12(32)築上町155.31(117.26)(北九州地方)

13(20)大任町153.42(135.11)(筑豊地方)

14(11)新宮町150.49(155.31)(福岡地方)

15(2) 小竹町 149.42(210.12)(筑豊地方)

16(18)福智町149.30(141.38)(筑豊地方)

17(17)遠賀町147.86(143.19)(北九州地方)

18(13)中間市146.62(145.34)(北九州地方)

19(21)行橋市143.60(134.73)(北九州地方)

20(27)みやこ町141.17(126.87)(北九州地方)

1)ひたすら他力本願の支店植民地奴隷。

2)地元の全国的有名企業はゼロ。 とにかくゼロ。

3)九州の人口背景をバックに国や企業が作ったものを福岡市単独の力だと自慢する。

4)地元から日本に影響を与えるような文化・流行発信能力はゼロ。

5)福岡ラブコレクションに代表されるように他都市が発信したものを福岡が発信としてパクル。

6)九州内の他県、他都市を田舎モンと蔑む(特に熊本市や北九州市)。自分もカッペなのには気づいていない。

7)他都市は決して認めない。負けそうになると人格攻撃や論点をそらしてごまかす。卑怯な気質。

8)とにかく自画自賛や自己過大評価がすごい。過去の武勇伝を得意げに語り自分を誇示したがる。

9)天神をとにかく異常に過大評価する。超高層ビルへのコンプレックスは日本一

10)高層ビルがないのは空港があるからだと言い訳する(実際は需要自体がない)一方で、

内陸都市の札幌には港が無いと攻撃する。

11)他都市の話題でスレが立つとボウフラのように湧き出てその都市に関して必死にネガキャン・こき下ろしを行う。

12)言う事がなくなるとひたすらオウム返しでごまかす。

13)社会人では、他人を蹴落として生き残ろうとするあまり、年下相手にも本気で争う。

14)冗談が通じず些細な事でも顔を真っ赤にして過剰反応を示す。

15)異常なほど自尊心が高い。自身の非は決して認めない。従って、傷付けられると異常に反応する。加えて執拗である。

16)極端な地元偏重思考。何でも一番だと思いたがる。

17)貧困から生じた他人蹴落とし精神によって、他地域を蔑み、蹴落とそうとする。

18)貧困による権利主張志向により、自動車に対し、歩行者と自転車運転者に『譲り合い精神』が無い。

19)生活安全面における「福岡市内は県内他地域より安全」説を強く信仰する。

20)福岡市内における事件ではまず他地域住民のしわざを強く疑う。また、脈絡なく他地域の悪口を言い始め、

話題を転換しようとしたり「~より福岡市内はマシ」説を唱え始める。

21)異常なまでにコンプレックスが強く他都市を攻撃する。一方でなぜか福岡市は周りから羨み妬まれてると勘違いしている。

22)麺類の話題が出ると聞いてもないのに「福岡市では~」「博多では~」とアピールを始める。と同時に他地域の料理を通ぶって批判する。

福岡が経験してきた偉大な記録集

・飲酒運転数全国 1位

・暴力団増率全国 1位

・拳銃押収数全国 1位

・〃発砲事件全国 1位

・郵便局強盗全国 1位

・犬猫殺処分全国 1位

・食品偽装数全国 1位

・放置自転車全国 1位

・部落同和数全国 1位

・生活保護率全国 1位

・自己破産率全国 2位

・ひったくり件数全国 1位

・暴走族数(95族)全国 1位

・自動販売機破壊全国 1位

・自動車当て逃げ全国 1位

・自動車税未納付率全国 1位

・110番(福岡西署)通報数全国 1位

・強姦件数(10万人あたり)全国 1位

・10歳~19歳の非行者率全国 1位

・未成年薬物検挙8年連続全国 1位

・最終学歴中卒率政令指定都市 1位

On my way home from this morning’s run, I found the following post at the entrance to a temple:

Reading: fukyo kunshu nyūmonnai

Meaning: くさいにおいのする野菜と、酒は、修行の妨げになるので、寺の中に持ち込んではならない、ということ

軍 (kun) refers to not only vegetables such as garlic, leeks, and onions, but also “nama-gusai” (foul-smelling or fishy) meat and seafood.

These things as well as alcohol are proscribed as they interfere with the religious training of the monks in the temple.

Another variant is:

山門 (sanmon) means the main entrance to a temple, the temple itself, or a Zen temple. In the past, temples were located in the mountains (山) far from human habitation (人里離れた).

葷=「くん」と読み、①くさみのある野菜、にんにく、にら。②生臭い肉と魚。 酒=アルコールを含む飲み物で、アルコールによって人の脳をまひさせるもの。 日本酒、焼酎(しょうちゅう)、紹興酒(しょうこうしゅ)など。 山門=「さんもん」と読み、①寺の正面の門。②お寺。禅寺。(お寺は本来、人里離れた山にあるべきなのでこのように言う)。 入る=「いる」と読み、はいるの古い言い方。 許さず=「ゆるさず」と読み、許さない。そのようにさせない。 修行=「しゅぎょう」と読み、仏教を学びその真理にもとづく悟りを得るために努力すること。 妨げ=「さまたげ」と読み、物事が進むのにじゃまになる。 寺=「てら」と読み、仏像を置いて僧侶が住み仏教の修行をするための建物。 戒律=「かいりつ」と読み、寺の僧侶が守るべき日常のきまりごと。不殺生、不偸盗、不邪淫、不妄語、不飲酒など。 戒壇石=「かいだんせき」と読み、戒律を守る目的で設けられた小さな結界を示す目じるしの石。結界石。 出家=「しゅっけ」と読み、一般の人が住んでいるこの世間を捨て仏門にはいること。 結界=「けっかい」と読み、寺の秩序を守るために決める一定の限られた場所。修行の妨げとなるものが入ることを許さない場所。

For more on this, go here.

I asked a group of college women to give me some examples of common and not so common Japanese abbreviations.

Old standards, of course, include OL (Office Lady), OB (Old Boy, as in an alumni network), and TPO (Time Place Occasion).

Recently popular ones are CA (Cabinet Attendant, i.e. stewardess) and KY (Kuki-o yomenai, referring to someone who can't read the mood of a situation; i.e. someone who just doesn't get it.) Not sure when flight attendants started being called CAs here. For the longest time they were called stewardesses, or "succhi" for short, but never F.A. Maybe because there is an “l” in “flight”.

The newer abbreviations the students offered up were rather funny, my favorite among them being PK.

"PK?" I asked. "PK, as in penalty kick?"

The girl laughed and said, "Yes, penalty kick." I could tell though that she wasn't telling me the truth.

"C'mon, what does it really mean?"

"It's embarrassing."

"Yes, but, you brought it up."

"パンツ食い込み. (Pants kuikomi)"

"A~h so~~~."

I don't recommend googling that when you're at work.

With all the talk in recent years about rising economic inequality in the U.S., I was curious to learn more about what the situation was like in Japan. In researching the issue, I came across an interesting site called heikin shūnyū ("average income", sorry Japanese only) which answers a lot of the questions people have about income and wealth in Japan. I will be translating some of my findings here, so check in on this post from time to time.

The first thing that caught my eye was the following:

"年収1000万円の手取りはいくらかと言いますと、ざっくりですが700~800万となります。ちなみに全体の中で、年収1000万以上もらえる人は全体の3~4%となりかなり少ないです。"

Take-home pay for someone earning ¥10,000,000 a year (or $84,873 at today's lousy exchange rate) amounts to about ¥7~8,000,000 ($59,000~68,000). Incidentally, only 3-4% earns over ten million yen a year. 3-4% of what is not clarified. I assume it is 3-4% of those who are working and earning an income.

According to another great site, Trading Economics, the labor force participation rate is 59.9%, giving Japan a workforce of 63,660,000 people. So, if I have calculated correctly, about two million people in Japan earn over 10 million yen a year. That would put them squarely in the top 5%, something I find hard to believe as an income of ¥10,000,000 isn't what I'd call "rich". (See below for the actual stats.)

How much money would you have to earn for you to feel like you're really raking it in? Minna no Koe ("Everyone's Voice") an online opinion survey run, I believe, by DoCoMo, asked this very question. More than 32,000 people took part in the survey and the results are as follows:

1. Over ¥10 million 48.8%

2. Over ¥8 million 19.3%

3. Over ¥5 million 12.0%

4. Over ¥20 million 6.3%

5. Over ¥100 million 3.9%

Interestingly, if you look at the answers of those still in their teens, "over ¥5 million a year" drops from third place to sixth and ¥20 million rises to third place. The second most common answer for those in their twenties, however, is "over ¥5 million a year", reflecting perhaps the harsh reality of working life in Japan today.

In 2010, 45,520,000 people in Japan received a "salary", the largest portion, or 18.1% (8.23 million people), earning between ¥3,000,000 ~ ¥3,999,999 a year. The next largest group, or 17.6% or wage-earners (about 8 million people) earned between ¥2,000,000 ~ ¥2,999,999.

Among men, the largest wage group (19.5% of the total) earned between ¥4,000,000 ~ ¥4,999,999. 26.8% of women earned more than ¥1 million and less than ¥2 million.

¥4,000,000 ~ ¥4,999,999 14.3%

¥5,000,000 ~ ¥5,999,999 9.4%

¥7,000,000 ~ ¥7,999,999 3.9%

¥10,000,000 ~ ¥14,999,999 2.8%

¥15,000,000 ~ ¥19,999,999 0.6%

¥2,500,000 ~ 0.2%

Those earning over ¥10,000,000 account for less than 5% of all wage earners, or about 2.27 million people.

Kakusa Shakai (格差社会, "gap-widening society") is a term you're sure to hear on TV when the discussion is about the economic in Japan. Like America, Japan has seen growing income inequality over the past few decades, though it hasn't been as conspicuous. Rather than go into the reasons for the rise in inequality, I would like to note that as of 2010, there were some 800,000 people who could be counted among the "well-to-do", namely, those earning over ¥20 million a year. By comparison, there were more than 20 million Japanese living in poverty.

(This is a rather old post that I have only just now transferred to my new blog. Will try to update the info in coming weeks.)