The Value of ¥100 yen in 1946: The Challenge of Accessibility Posed by Japanese Literature in Translation (long version)

整理がすんでから、私はお母さまからお金をいただき、百円紙幣を一枚ずつ美濃紙に包んで、それぞれの包みに、おわび、と書いた。

“When I had finished disposing of the wood, I asked Mother for some money, which I wrapped in little packets of 100 yen each. On the outside I wrote the words ‘With apologies.’”[1]

—Dazai, Osamu, The Setting Sun (translated by Donald Keene)

When reading literature of a culture different from one’s own, it is not uncommon for the reader to get tripped up by the cultural and historical references lurking in the prose. Questions arise that cannot be readily answered, and accessibility, the quality of easily grasping or appreciating a work of art, suffers.

Despite their extraordinary success in the Japanese literature market, best-selling authors, such as mystery writer Akagawa Jirō,[2] and historical novelists Shiba Ryōtarō[3] and Yoshikawa Eiji,[4]remain, for the most part, untranslated and therefore little known outside of Japan. Of all Japan’s authors, both past and present, however, one has managed to break through the language and cultural barriers facing the Japanese writer: Murakami Haruki. The social cataloging website Goodreads currently lists nineteen of Murakami’s works in its ranking of “Best Japanese Books”, seven of which are ranked among the top ten:

Norwegian Wood by Murakami Haruki

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Murakami Haruki

Kaftka by the Shore by Murakami Haruki

Battle Royal by Takami Kōshun

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World by Murakami Haruki

1Q84 by Murakami Haruki

After Dark by Murakami Haruki

Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto

Out by Kirino Natsuko

Sputnik Sweetheart by Murakami Haruki[5]

Dazai Osamu’s 1947 novel Shayō (The Setting Sun), which “lamented the demise of true noblesse oblige and professed to find a philosophy for the current [postwar] epoch in the motto ‘love and revolution’” ranks a distant sixty-fourth.[6]

One reason, I believe, that Murakami Haruki has been so successful outside of Japan is the conspicuous absence of Japanese cultural references. Singer/songwriter John Wesley Harding brought this to the novelist’s attention in 1994, shortly after the release of the English translation of Murakami’s sixth work of fiction Dance Dance Dance:

John Wesley Harding (JWH): I read in one review that the big thing an English reader will miss in the translation is how shocking the Americanness of your books is.

Haruki Murakami (HM): Americans are different. Americans are strange because they don’t believe that we have Dunkin’ Donuts or McDonald’s or Levi’s or Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen in Japan.

JWH: You have it all.

HM: We have it all. We grew up with those things. They think Dunkin’ Donuts and Coca Cola and Budweiser and Bob Dylan are their own.

JWH: I have the impression that people over there got annoyed because what you were doing was not “Japanese.”

HM: Yes. There is a very strong tradition of Japanese literature. They claim that the beauty of Japanese language and Japanese literature is special and only Japanese can understand it. Japaneseness, you could say. They say it does not travel. I think they might be right, because our culture and language are so different from the western ones. Haiku cannot be translated, that is true. But that is not all, that is not everything. I am Japanese and am writing a novel in Japanese, and, in that sense, I am different from you. But talking with you like this face to face, I don’t think I am so different from you. We have many things in common. What I want to say is, there should be other ways to convey Japaneseness. True, I am not exotic, but that doesn’t mean that I am not a Japanese novelist. When I’m describing the city of Tokyo, it is not the real Tokyo. It’s just a colorful city. I need very artificial, very strange, weird streets. That’s what I want, and yet they say it’s not realistic. About six years ago I wrote “Dunkin’ Donuts” kind of things; that helped me a lot to create kind of a Blade Runner place.

JWH: Hard-Boiled Wonderland is very Blade Runner in a way, isn’t it?

HM: It’s a nowhere city. And I needed that. But these days, I don’t need those kinds of things anymore. Because I can create my own world. Ten years ago I needed to get away from Japanese society, I wanted to get away from that tradition.[7]

Scan through Murakami’s earlier works, such as his debut novel, Kaze no Uta wo Kike (1979), translated in 1987 by Alfred Birnbaum as Hear the Wind Sing, and you may miss the subtle hints of the Japanese setting:

She was sitting at the counter of J’s Bar looking ill at ease, stirring around the almost-melted ice at the bottom of her ginger ale glass with a straw. “I didn’t think you’d show.”

She said this as I sat next to her; she looked slightly relieved. “I don’t stand girls up. I had something to do, so I was a little late.”

“What did you have to do?”

“Shoes. I had to polish shoes.”

“Those sneakers you’re wearing right now?”

She said this with deep suspicion while pointing at my shoes.

“No way! My dad’s shoes. It’s kind of a family tradition. The kids have to polish the father’s shoes.”

“Why?”

“Hmm...well, of course, the shoes are a symbol for something, I think. Anyway, my father gets home at 8pm every night, like clockwork. I polish his shoes, then I sprint out the door to go drink beer.”

“That’s a good tradition.” “You really think so?” “Yeah. It’s good to show your father some appreciation.” “My appreciation is for the fact that he only has two feet.” She giggled at that. “Sounds like a great family.” “Yeah, not just great, but throw in the poverty and we’re crying tears of joy.” She kept stirring her ginger ale with the end of her straw. “Still, I think my family was much worse off.” “What makes you think so?” “Your smell. The way rich people can sniff out other rich people, poor people can do the same.” I poured the beer J brought me into my glass. “Where are your parents?” “I don’t wanna talk about it.” “Why not?”

“So-called ‘great’ people don’t talk about their family troubles. Right?” “You’re a ‘great’ person?” Fifteen seconds passed as she considered this. “I’d like to be one, someday. Honestly. Doesn’t everyone?

I decided not to answer that. “But it might help to talk about it,” I said. “Why?” “First off, sometimes you’ve gotta vent to people. Second, it’s not like I’m going to run off and tell anybody.” She laughed and lit a cigarette, and she stared silently at the wood-paneled counter while she took three puffs of smoke.

“Five years ago, my father died from a brain tumor. It was terrible. Suffered for two whole years. We managed to pour all our money into that. We ended up with absolutely nothing left. Thanks to that, our family was completely exhausted. We disintegrated, like a plane breaking up mid-flight. The same story you’ve heard a thousand times, right?”

I nodded. “And your mother?” “She’s living somewhere. Sends me New Year’s cards.”[8]

The only indication Murakami offers his readers that this story is taking place in Japan is the casual reference to New Year’s cards, or nengajō. Nothing else, not the names of the characters—J, the girl, the Rat, the twins—the music they listen to—Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Beach Boys, to name a few—the beverages they drink—beer and whiskey—or the books they read—Molièri and Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ—clue the reader in.[9]

僕は肯いた。「お母さんは?」

「何処かで生きてるわ。年賀状が来るもの。」[10]

Moreover, it is not unusual for Japanese readers to feel a sense of incongruity when reading Murakami in the original, as Ōmori Kazuki, director of the 1981 film adaptation of Hear the Wind Sing related in an interview with the Asahi Shimbun:

“In 1981, [Ōmori] visited the Peter Cat jazz cafe that Murakami operated in Tokyo’s Sendagaya to ask the author for permission to adapt his novel for the big screen. Omori tried to establish a connection by telling Murakami that he attended the same junior high that he had, and his homeroom teacher was Murakami’s literature teacher.

“Murakami said ‘no problem’ to his request, but as Omori [sic] started writing the script based on the novel, he soon found it difficult to reproduce the author’s printed world.

“‘You cannot just let actors recite lines from Murakami’s novels, because no Japanese person actually talks like his characters do,’ Omori recalled.

“It then struck him that the lines are very similar to the Japanese subtitles that appear on the corner of screens in foreign films. It also became apparent that the fragmented storyline of ‘Hear the Wind Sing’ resembles films by director Jean-Luc Godard and other French New Wave works.”[11]

Murakami’s deliberate shunning of Japanese culture and even language in his writing may have made him popular with readers at home and lent his writing accessibility abroad, but it also led to sharp criticism among the literati of Japan, as professor of Japanese Literature and frequent Murakami translator Philip Gabriel noted in an interview:

“The early novels were not well-received by Japanese critics. ‘He wrote in a style that the literary establishment found startling and puzzling,’ says Gabriel.

“His scorn for Japanese literary tradition, his conversational writing style, and constant references to Western culture were seen as an assault on Japanese literary conventions. Writers such as Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe, initially branded him as a lightweight pop talent.

“But as Philip Gabriel puts it: ‘His early works capture the spirit of his generation—the lack of focus and ennui of the post-Student Movement age.’”[12]

Another novelist who captured the spirit of his generation was Dazai Osamu. “The immediate status as a classic [of his 1947 novel Shayō (The Setting Sun),” writes historian John W. Dower, “came from more than just the morbid conjunction of the decadence and suicide it depicted with the decadence and suicide of the author. No other work captured the despondency and dreams of the times so poignantly. Whatever he may have lacked, Dazai was not lacking in a self-pity that resonated strongly with the deep strain of victim consciousness then pervading society.”[13]

Donald Keene, the esteemed scholar and translator of Japanese literature, wrote in the introduction of his 1956 translation of Shayō that “The Setting Sun derives much of its power from its portrayal of the ways in which the new ideas have destroyed the Japanese aristocracy. The novel created an immediate sensation when it first appeared in 1947. The phrase ‘people of the setting sun,’ [斜陽族, Shayō-zoku] which came to be applied, as a result of the novel, to the whole of the declining aristocracy has now passed into common usage and even into dictionaries.”[14]

In spite of Shayō’s significance among the wealth of postwar Japanese literature, the novel provides a number of challenges to the foreign reader. An innocuous passage like the one quoted at the very beginning of this paper can throw insuperable obstacles at even the most well-versed student of Japanese culture and literature, sending him tumbling down a Wikipedia rabbit hole.

整理がすんでから、私はお母さまからお金をいただき、百円紙幣を一枚ずつ美濃紙に包んで、それぞれの包みに、おわび、と書いた。

“When I had finished disposing of the wood, I asked Mother for some money, which I wrapped in little packets of 100 yen each. On the outside I wrote the words ‘With apologies.’”

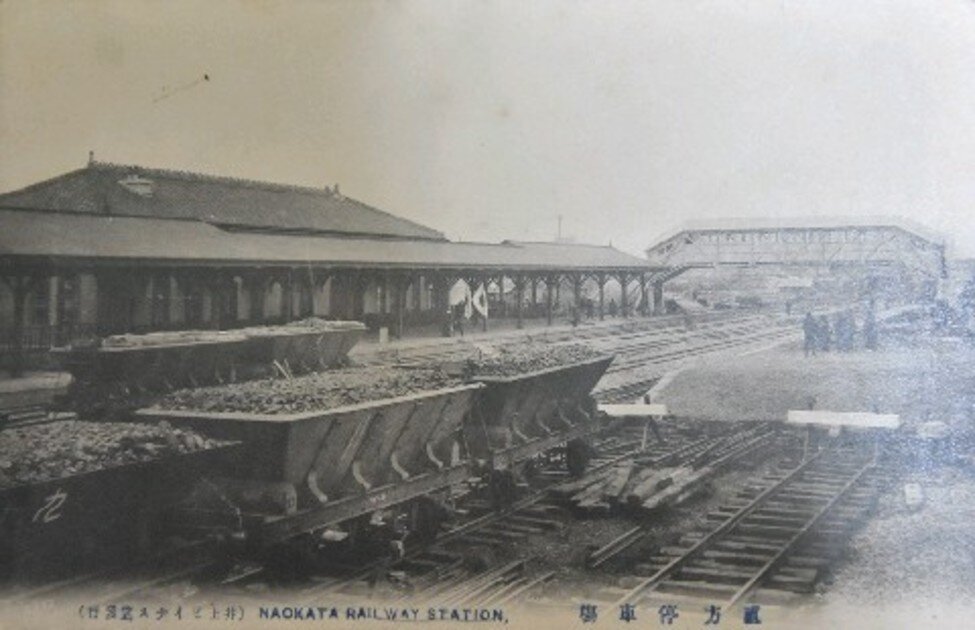

The Setting Sun is set in years immediate following the end of World War II. Kazuko, the narrator of the story, and her mother have recently moved from Tōkyō to a Chinese-style villa in Izu, Shizuoka.

お父上がお亡くなりになってから、私たちの家の経済は、お母さまの弟で、そうしていまではお母さまのたった一人の肉親でいらっしゃる和田の叔父さまが、全部お世話して下さっていたのだが、戦争が終わって世の中が変り、和田の叔父さまが、もう駄目だ、家を売るより他は無い、女中にも皆ひまを出して、親子二人で、どこか田舎の小綺麗な家を買い、気ままに暮したほうがいい、とお母さまにお言い渡しになった様子で、お母さまは、お金の事は子供よりも、もっと何もわからないお方だし、和田の叔父さまからそう言われて、それではどうかよろしく、とお願いしてしまったようである。

“After my father died, it was Uncle Wada—Mother’s younger brother and now her only surviving blood relation—who had taken care of our household expenses. But with the end of the war everything changed, and Uncle Wada informed Mother that we couldn’t go on as we were, that we had no choice but to sell the house and dismiss all the servants, and that the best thing for us would be to buy a nice little place somewhere in the country . . .”[15]

The change, to which Uncle Wada alludes, is the societal upheaval brought about after the end of the Pacific War in August 1945, and the new constitution, which became law on 3 November 1946, it is worth noting, on Meiji Setsu, or Emperor Meiji’s birthday, celebrated in Japan today as Bunka no Hi, or Culture Day. The constitution went into effect six months later on 3 May 1947, Kempō Kinenbi, or Constitution Memorial Day.

Article 14 of the Japanese constitution states:

第十四条

1.すべて国民は、法の下に平等であって、人種、信条、性別、社会的身分又は門地により、政治的、経済的又は社会的関係において、差別されない。

2.華族その他の貴族の制度は、これを認めない。

3.栄誉、勲章その他の栄典の授与は、いかなる特権も伴はない。栄典の授与は、現にこれを有し、又は将来これを受ける者の一代に限り、その効力を有する。

1. All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin.

2. Peers (華族, kazoku) and peerage (貴族, kizoku) shall not be recognized.

3. No privilege shall accompany any award of honor, decoration or any distinction, nor shall any such award be valid beyond the lifetime of the individual who now holds or hereafter may receive it.”

Kazuko and her mother are members of the soon-to-be abolished Japanese aristocracy, known as the Kazoku (華族, lit. “exalted lineage”). The Kazoku, or hereditary peerage of the Empire of Japan, was created after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 by merging the Kuge (公家, royal family), which had lost much of its status with the rise of the Shogunate in the 12th century, with the former Daimyō (大名, feudal lords) of the Edo Period (1603-1868).[16] [17]

Although the number of families in the Kazoku peaked at 1016 families in 1944, the Constitution of Japan effectively did away with the use of noble titles outside the immediate Imperial family. Nevertheless, many descendants of the former Kazoku continue to occupy positions of influence in society today. One such person, who comes to mind, is Morihiro Hosokawa, the 50th Prime Minister of Japan (August 1993 to April 1994). Hosokawa was the eldest grandson of Moritatsu, 3rd Marquess Hosokawa, and the 14th Head of the Hosokawa clan. His maternal grandfather was the pre-war Prime Minister Prince Fumimaro Konoe.[18]

As for that 100 yen? According to the Bank of Japan, 100 yen in the following years was worth (in 2005 yen):

Value of ¥100

(in 2005 yen)

1931 ¥888,903

1932 ¥801,084

1933 ¥699,895

1934 ¥686,171

1935 ¥668,913

1936 ¥641,795

1937 ¥528,537

1938 ¥501,055

1939 ¥453,547

1940 ¥405,180

1941 ¥378,214

1942 ¥347,751

1943 ¥324,976

1944 ¥286,718

1945 ¥189,809

After the end of the war, Japan experienced runaway inflation which would last for over four years. Wholesale prices doubled by the end of 1945 and continued to rise. In the first year of the occupation, prices rose by 539 percent. 1.4 kilograms of rice, which had cost 2.7 yen in June of 1946, would end up costing 62.3 yen by early 1950.[19]

In his National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning history of Japan’s occupation, Embracing Defeat, John W. Dower provides the following example of what life immediately after the war was like:

“Okano Akiko, a middle-class Osaka housewife writing for a women’s magazine in 1950, offered an intimate picture of what ‘enduring the unendurable’ had been like for her family. Her husband, a teacher at a military-affiliated school, became unemployed after the surrender but soon found a low-level job as a clerk at a salary of 300 yen a month. At that time, about a quart and a half of rice cost 80 yen, so to make ends meet, they began selling off their belongs.

“In the confusion of early 1946—when a ‘new yen’ was introduced in a futile attempt to curb inflation—the company employing Okano’s husband went out of business, leaving him with a mere 900 yen in severance pay . . . The price of rationed riced tripled in 1946, but, out of principle as well as poverty, the family tried to use the black market as little as possible.

“Eventually, her husband found a job as schoolteacher at a salary of 360 yen per month. They had little choice but to continue to sell their possessions, purchasing black-market goods about eight times monthly, at a cost of roughly 400 yen per month . . . Her husband lost his job again when the school ran into financial difficulties, this time receiving only 50 yen as severance pay. He, too, began to suffer noticeably from malnutrition, his entire body beginning to swell up . . .

“In 1948, the food situation improved somewhat, although potatoes remained the mainstay of the family diet. Both wife and husband fell seriously ill that year and went deeply into debt. In 1949, another child was born, and meat and fish finally became plentiful again, although it was still a struggle to make ends meet, as rent and food prices continued to climb. As 1950 began, her husband found a teaching position at a college. For the first time since the war ended, they could live on his income; and so, Okano wrote, she was finally able to think about the quality of family life, not mere survival.”[20]

In 1945, the value of 100 yen, according to the Bank of Japan, was equivalent to \19,200 in 2012. One must keep in mind, however, this is the value of the yen based on the prices companies used when conducting business among themselves. Some, looking into wages paid or prices in the market in the postwar years put the value of 100 yen in 1945 at anywhere from four thousand to fifty thousand yen.

Whether ¥100 in those days was equivalent to four thousand yen, twenty-thousand yen, or even fifty thousand today was all rather academic to Kazuko and her mother, the reader will learn in the second chapter, because they will receive a letter from their Uncle Wada informing them that:

「もう私たちのお金が、なんにも無くなってしまったんだって。貯金の封鎖だの、財産税だので、もう叔父さまも、これまでのように私たちにお金を送ってよこす事がめんどうになったのだそうです。それでね、直治が帰って来て、お母さまと、直治と、かず子と三人あそんで暮していては、叔父さまもその生活費を都合なさるのにたいへんな苦労をしなければならぬから…」

“. . . our money is all gone, and what with the blocking of savings and the capital levy, [Uncle Wada] won’t be able to send us as much as he has before. It will be extremely difficult for him to manage our living expenses, especially when Naoji arrives [from the South Pacific] and there are three of us to take care of.”[21]

In December of 1945, Kazuko and her mother leave their home in Nishikata Street in Tōkyō for a modest Chinese-style house in Izu, a villa which Uncle Wada purchased from a viscount (子爵, shishaku), who we may infer is also feeling the financial pinch brought about by the societal changes. Their troubles, however, are only just beginning as Kazuko laments:

「もしお母さまが意地悪でケチケチして、私たちを叱って、そうして、こっそりご自分だけのお金をふやす事を工夫なさるようなお方であったら、どんなに世の中が変っても、こんな、死にたくなるようなお気持におなりになる事はなかったろうに、ああ、お金が無くなるという事は、なんというおそろしい、みじめな、救いの無い地獄だろう、と生れてはじめて気がついた思いで、胸が一ぱいになり、あまり苦しくて泣きたくても泣けず、人生の厳粛とは、こんな時の感じを言うのであろうか、身動き一つ出来ない気持で、仰向に寝たまま、私は石のようにじっとしていた。」

“If Mother had been mean and stingy and scolded us, or had been the kind of person who secretly devises ways to increase her fortune, she would never have wished for death that way, no matter how much times had changed. For the first time in my life I realized what a horrible, miserable, salvationless hell it is to be without money. My heart filled with emotion, but I was in such anguish that the tears would not come.”[22]

To make matters worse, we learn in Chapter Two that Kazuko has accidentally started a fire:

「私が、火事を起しかけたのだ。私が火事を起す。私の生涯にそんなおそろしい事があろうとは、幼い時から今まで、一度も夢にさえ考えた事が無かったのに。お火を粗末にすれば火事が起る、というきわめて当然の事にも、気づかないほどの私はあの所謂「おひめさま」だったのだろうか。」

“I was responsible for starting a fire. That I should have started a fire, I had never even dreamed that such a dreadful think would happen to me. I at once endangered the lives of everyone around me and risked suffering serious punishment provided by law.”[23]

In the past, fires were so frequent and destructive that a proverb remains to this day: “Fires and quarrels are the flowers of Edo (Tōkyō)” (火事と喧嘩は江戸の花, Kaji to kenka wa Edo no Hana). The threat of fire was so great in the densely populated capital, where most of the structures were made of highly flammable wood and paper, that even accidental fires (失火, shikka) were punishable with up to thirty days house arrest during the Edo Period (1603-1868). In those days, a person found guilty of arson would be paraded around town on a horse (馬で市中引廻し, uma de shichū hikimawashi) then burned to death (火刑, kakei).[24] Although such severe punishment was a thing of the distant past by 1946, the gravity of Kazuko’s carelessness hit home nonetheless, and she made the rounds to beg forgiveness and offer an token compensation of one hundred yen to those she had troubled:

「まず一ばんに役場へ行った。村長の藤田さんはお留守だったので、受附の娘さんに紙包を差し出し、『昨夜は、申しわけない事を致しました。これから、気をつけますから、どうぞおゆるし下さいまし。村長さんに、よろしく』とお詫びを申し上げた。」

“I called first at the village hall. The mayor was out, and I gave the packet [of money] to the girl at the reception desk saying, ‘What I did last night was unpardonable, but from now on I shall be most careful. Please forgive me and convey my apologies to the mayor.’”[25]

It is at this point, that the weary reader must crawl out of the rabbit hole and dust himself off before moving on to Chapter Three.