Shuri Castle's Shurei Gate (守礼門) in February 2014 at the beginning of the tourism boom and again in October 2020 during the pandemic.

To the Knackers

I had an interesting conversation with a friend a few years ago

For the past several years Kei has been importing riding horses to Japan from Germany and early on I helped her out with correspondence, drawing up preliminary contracts, and so on. The reason she came to me is that, as I have mentioned elsewhere, I once lived in Germany and can still understand the language somewhat. Kei only knew a handful of words: ja, nein, danke schön, bitte. In the kingdom of the blind, they say, the one-eyed man is king.

Fortunately for her and me, most of the Germans we were dealing with spoke damn good English. (That wasn’t the case in the 1980s.)

Two years later, her business has expanded with small, yet encouraging steps and has had her traveling to Europe on a monthly basis, shopping for horses, investing in them, and participating in international equestrian events as a judge. Reading this, you might get the impression that Kei is a fabulously wealthy woman, but nothing could be further from the truth: she is, in fact, a modestly working class, single mother who has gotten by on her wits and creativity. I have a lot of respect for the woman.

Anyways, Kei will be making two trips to Germany again next month to introduce a German breeder/trainer to her Japanese client who’s interested in buying a “high level horse”. Until now, Kei has been buying horses with somewhat humble pedigrees for eventing [1] enthusiasts and riding clubs in Kyūshū and was excited to finally deal in some top level horses.

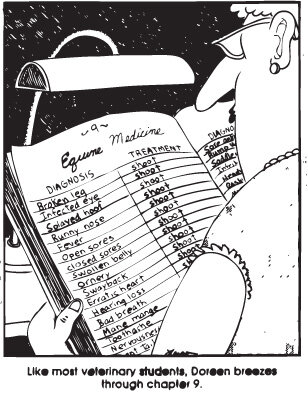

Hearing this, I joked that there were four levels of horses: high-level, mid-level horses, low-level, and glue.

This is where the conversation became interesting.

Kei laughed then told me about a local company called Kohi Chikusan owned by a Mr. Kohi (sounds like the Japanese pronunciation of coffee). Kohi, she said, takes “compromised” horses off of stables’ hands and “makes arrangements for them”. Some of these horses are put down, some are resold and show up, seemingly miraculously, at rival stables, and a few are sold for horsemeat. (Don’t worry, most of the horsemeat used in the delicacy basashi[2] comes from Australia.)

“Whenever a horse acts up or doesn’t respond well,” Kei said laughing, “we tell it we’re going to call Kohi-san.”

I couldn’t help but be reminded of the scene in George Orwell’s classic Animal Farm when Boxer is sent to the glue factory.

I tried to google Kohi Chikusan, but couldn’t find anything.

“They don’t have a website,” Kei said.

“No, I don’t suppose they would.” Talk about a niche business!

Kei explained that they had to use the service because when a horse weighing five hundred kilos dies it’s nearly impossible to move it. Rigor mortis sets in within a few hours after death, freezing the horse in the position that it died in, and the only way to get it out of a stable is to chain it to the back of a tractor and drag it out. Not exactly the kind of thing you want your paying customers to see when they’re practicing their jumps.

“So, whenever a horse becomes too ill for the veterinarian to treat, we call Kohi-san.”

“Kohi isn’t a very common name, is it?” I said.

“That’s because he’s a Buraku-min,” she replied matter-of-factly. “A lot of people involved in that kind of business come from the Buraku-min. Meat handlers, too.”

This morning when I was looking into the family names of the Buraku, I learned that while the caste system of feudal Japan was abolished in Japan in the early years of the Meiji Period and all Japanese were assigned family names, the Buraku-min were given family names that would make them still recognizable from ordinary Japanese a hundred years later. These names apparently include the following Chinese characters: 星 (star); body parts, such as 手 (hand), 足 (foot), 耳 (ear), 頭 (head), 目 (eye); the four points of the compass, 東 (east), 西 (west), 南 (south), 北 (north); 大, 小 (large and small); 松竹梅 (pine, bamboo, plum), 神, 仏 (god and buddha) and so on. Examples include: 星野 (Hoshino), 小松 (Komatsu), 大仏 (Osaragi), 神川 (Kamikawa), 猪口 (Inoguchi/Inokuchi)、熊川 (Kumakawa)、神尾 (Kamio), and so on. (Beware of assuming that everyone with these kinds of names are Buraku-min, they are not.)

I wrote about the Buraku-min in Too Close to the Sun. The passage from my novel discussing these unlucky people has been included below:

In the afternoon, I’m summoned to the interrogation room where Nakata and Ozawa are waiting for me.

Both of them are in an easy, light-hearted mood today. The desk is free of notebook computers; there are no heavy bags filled with thick folders of evidence on the floor.

Ozawa is slouched comfortably in his seat, tanned fingers locked behind his head.

"What was the name of that Korean restaurant you mentioned last week?" he asks.

"Kanō," I say, taking my usual seat, still bolted to the floor.

"Where was that again?"

"It's in Taihaku Machi, a rough neighborhood near the Chidori Bridge."

"Taihaku Machi?"

"Along the Mikasa River, across from Chiyo Machi."

"Chiyo? Ugh!" he says grimacing. "Why is it that all the good Korean restaurants have to be located in the shittiest part of town?"

Nakata asks me if I know what Eta is. I shrug.

Ozawa tries to look it up in his electronic dictionary, but can't find it.

"Figures," he grumbles.

"How do you write it," I ask.

Ozawa scribbles the following two kanji in his notebook: 穢多 The first character, 穢, he says, can be read as kitanai and means filthy. It can also be read as kegare. Finding the entry, Ozawa spins his dictionary around to show me that kegare means impurity, stain, sin, and disgrace. The other, more common character, 多, pronounced ta, or ôi, means plenty, or many. So, eta, connotes something that is abundantly filthy or impure.

Then it hits me that the eta Nakata is alluding to is yet another word that editors of Japanese-English dictionaries conveniently omit: buraku-min (部落民).

Map indicates “Eta Mura” or the area where the outcasts lived.

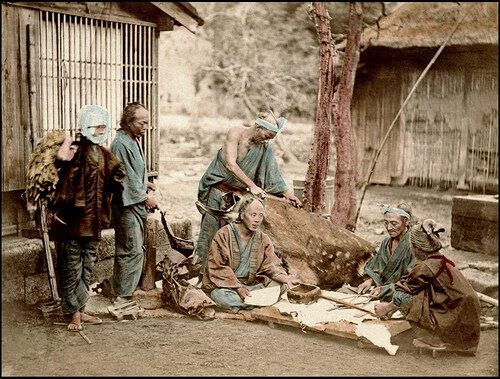

The Buraku-min (lit. hamlet people) were a class of outcasts in feudal Japan who lived in secluded hamlets outside of populated areas where they engaged in occupations considered to be vitiated with death and impurity such as butchering, leather working, grave-digging, tanning and executions.

For the Shintō who believed that cleanliness was truly next to godliness, those who habitually killed animals or committed otherwise heinous acts were considered to be contaminated by the spiritual filth of their acts and thereby evil themselves. As this impurity was believed to be hereditary, Buraku-min were restricted from living outside their designated hamlets (buraku) and not allowed to marry non-Burakumin. In some cases they were even forced to wear special costumes, footwear, and identifying marks.

The Emancipation Edict of 1871 intended to eradicate the institutionalized discrimination and the former outcasts were formally recognized as citizens. However, thanks to family registries, known as koseki, which are assiduously kept by officials in every Japanese city, town and village, it was easy to identify who was Buraku-min from their ancestral home, and discrimination against them continued.

Shortly after coming to Japan, the wife of a company president once confided to me that she and her husband might be willing let his daughter, God forbid, marry an ethnic Korean, but would never countenance her marrying a Buraku-min. He would never hire one, either.

"Never? Regardless of the person's talent?" I asked.

"The damage to the image of my husband's company would be far greater than any benefit such an employee could ever bring."

And that's how it goes in this sophisticated democracy: you can still be discriminated against just because your great-great-great grandfather had a shitty job.

Today there are some four thousand five hundred Dôwa Chiku, or former Buraku communities that were designated by the government in the late sixties for the so-called assimilation projects. Over the next three decades, housing projects and cultural facilities were constructed, and infrastructure improved in the dowa chiku (assimilation zones) to raise the standard of living of the residents of those areas.

There are an estimated two million descendents of Buraku-min in Japan today, most of whom live in the western part of the country, particularly in the Kansai area around Osaka, and in Fukuoka Prefecture.

"Chiyo’s a Dōwa Chiku," Nakata says. "Crawling with Eta."

"I know," I say.

“You do?” They seem surprised.

The fact was first brought to my attention many years ago when I was searching for an apartment. A kindly old woman I had just met was all too eager to help me. She pulled out a map of the city from her handbag and, without elaborating, began crossing out "undesirable places", many of them located along the rivers. When I asked why, she said: "Trust me, you don’t want to live there." And so I did, finding a reasonably priced one-room apartment in one of the tonier areas near Ōhori Park.

"Those people are nothing but trouble," Nakata says. "Riffraff the lot of them."

"You’re kidding, right?"

He leans forward, resting his rotund chest against the desk. "There were a lot of Eta in my hometown when I was young. Nothing, but trouble. If you ever got in a fight with one these Eta bastards, the next thing you know, you're surrounded by a group of them. Sneaky guttersnipes."

The thought of Nakata as a chubby little kid in glasses getting the snot beaten out of him by a gang of Buraku boys almost causes a laugh to percolate out of me.

"Surely not all of them?" I say.

"Yes, all of them," Nakata replies and sits back, brushing his wimpy salt and pepper mustache with his fingers.

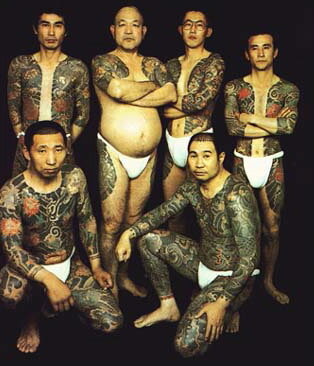

Ozawa asks if I've heard of the Yamaguchi Gumi.

"The yakuza gang?"

"Yeah. Biggest crime syndicate in Japan. It's mostly comprised of these Eta scum."

"Most yakuza gangs are," says Nakata.

"I had no idea," I say.

"Nothing but trouble," Nakata says again.

"Say, what's the deal with the girls working the food stalls at the festivals," I ask. "I've heard they're run by the yakuza."

"They are. The girls are Eta bitches," Nakata replies.

"Pretty damn cute bitches," I say.

Dregs of Japanese society or not, quite a few of the young girls working at festivals are knockouts.

After fifteen years, Japan can still be an enigmatic country. One thing I've never been quite able to figure out is why the best-born Japanese girls are so homely. The ugly daughters of good families, I call them.

"Cute they are," says Ozawa snickering. "Cute they are. Every evening in Chiyo you'll see small armies of the chicks all dolled up hopping into taxis. Off to Nakasū. Shoot the breeze with one of them and some yakuza prick will strut on up and start breakin' your balls as if you were hitting on his woman. That's when the badge comes in handy, of course. Hee-hee."

"I wouldn't go near one of those girls with a barge-pole," Nakata pipes in.

As if the man has to beat the girls away with a stick.

"There's something I've been meaning to ask you," I say.

"Shoot," says 0zawa.

"A lot of the guys in the joint here, and last week at the jail at the Prefectural Police Headquarters, for that matter, are obviously yakuza."

"Yeah?"

"I don't get it."

"Don't get what?"

"In the States, there is, among so many crime syndicates, the Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, right? You know, The Godfather, and all that. Well, these guys used to bend over backwards to deny that the Mafia even existed. Here in Japan, though, the yakuza practically advertise their criminal activity with missing pinkies, lapel pins, and bodies covered in tattoos."

It borders on the absurd. If cops were seriously interested in taking a bite out of crime, the first thing they ought to do is clamp down on these shady characters. The police, of course, will counter that they aren't in the business of preventing crime: they can't make any arrests until a crime had been committed. Which begs the question of why someone like me has to molder away in a stinking cell.

"The ones who strut and swagger," Ozawa says, "are good-for-nothing punks. All bluster and no brawl. They kick up a fuss because they don't have the balls to actually do anything. No, the yakuza you really have to watch out for are the quiet ones, the ones who never raise their voices, or show their tattoos. Those bastards will whack a person at the drop of a hat."

“Better get a hat with a strap then.”

Thank you for reading. This and other works are, or will be, available in e-book form and paperback at Amazon. Support a starv . . . well, not quite starving, but definitely peckish: buy one of my books. (They’re cheap!) Read it, review it if you like it (hold your tongue if you don’t), and spread the word. I really appreciate it!

© Aonghas Crowe, 2010. All rights reserved. No unauthorized duplication of any kind.

注意:この作品はフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are (wink, wink) fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Wrong, Very Wrong

A few months before I was to move to Japan, I looked at a map of the world I had on my bedroom wall† and traced my finger in a horizontal line from Fukuoka City, across the Pacific Ocean, all the way to San Diego, California.

"Perfect!" I said to myself.

Having moved to Portland, Oregon after living in Southern California for the first half of my life, I was never quite able to tame the longing in my heart for the subtropics.

I'd also had enough of Oregon's miserable weather, the rain, the drizzle, the sprinkling, the showers, and the constantly gray, overcast skies. I was sick of the mud on my shoes, the musty smell of Pendleton wool as I chopped wood for the fire, and the firewood that was always too damp to catch fire. I'd also had it up to here with the runny nose, the pasty white skin, the bronchitis. I wanted to escape. And now Japan was beckoning me like Bali Hai.

And so, looking at that map, I recall saying to myself, "I guess I won't be needing my sweaters. Won't need that heavy coat, either. Gloves? I'll toss those in the Goodwill pile . . ."

And then I came to Japan and for those first few weeks in late March I nearly died from exposure (and hunger, but that's another story).

On March 11th, 2015 it snowed, if you can believe it? Not enough to stick, of course, but enough to remind you that living in a subtropical climate comes with no guarantees.

I wore four layers, a scarf, and my heavy peacoat when I took my son to kindergarten. I was still cold. When I took a look at today's weather, I was both amused and chagrined to discover that it was 18°C in Portland.

All I can say is, thank God I don't live in Korea.

†Some boys have pictures of large-breasted women on their walls. I had maps and posters of world destinations. That is the kind of nerd I was. (Am.)

Matchmaker, Matchmaker

The word nakōdo (仲人) means "matchmaker or go-between". In the past, when arranged marriages or o-miai were more common, the nakōdo would seek out suitable prospects for a man or woman and introduce them with photos and a resume.

Now, something I didn't until very recently know about this o-miai business is the money involved. A matchmaker could earn a million yen or more for a successful match, quite a bit of cash ($10K~). And he or she would be given gifts every summer and winter until his or her death. Not a bad gig.

Insurance salesladies often took on this service as a side business as they had a large number of contacts and were privy to all kinds of private information.

Even today, when more and more couples are marrying for "love", nakōdo are still invited to perform a ceremonial role at the wedding itself. If the groom is, for instance, a doctor, he might invite one of his professors or an important doctor from his hospital to do the duty. The nakōdo will receive from ¥500,000 to over ¥1,000,000 for this service, which usually amounts to sitting in front of everyone at the wedding, making a long and tedious speech and then getting drunk.

As of today, I hereby throw my hat into the nakōdo business for the low, low cost of ¥350,000 a pop. I'm sure I can scrounge up a mourning coat somewhere and, more importantly, I promise I will not to get too stinking drunk and embarrass everyone at the nuptials.

You know where you ca--HIC--can find me.

Big Balls

At my soccer team's New Year's party a few years back, Vasily stood up to make a toast: "When men are in their teens and twenties, they play soccer. When they are in their thirties and forties, they play tennis. When they are in their sixties, they play golf. The older they get, the smaller their balls. I'm happy to say that all of us still have large balls."

I interrupted our Moldovan captain: "Vasily, I have some sad news for all of you . . . And this is difficult for me to say, but I'm afraid I won't be playing soccer anymore."

"No!"

"From next week," I said, "I'll be playing basketball, instead."

The Way of the Bow

My long walks continued. I’d been coming down with such a severe case of cabin fever that even the heaviest of showers was no longer enough to keep me inside. I’d even traded in my flimsy convenience store umbrella for one from Paul Smith costing ten times as much, just so that I could get out of my apartment and out of my head, as often as possible. Call me Thoreau; Fukuoka, my Walden.

One afternoon, as I was returning from one of my longest walks yet that had my shins and arches aching with a dull, throbbing pain, I dropped in at the Budōkan to see what kind of martial arts were taught there.

At the entrance was a bulletin board with a schedule of classes. On Saturday evenings, big boys in diapers pushed themselves around a clay circle. Sumō wasn’t really my cup of tea, which is just as well; of all my blessings, girth is not one of them. Three evenings a week, the kendō members met to whack each other senseless with bamboo sticks. That wasn’t quite what I was looking for either.

I walked over to a small window, stuck my head in, and said excuse me in Japanese, disturbing three elderly men from their naps.

“You really gave my heart a start,” said one of the men as he approached the window.

“Um, sorry about that.”

“Wow! Your Japanese is excellent.”

“Tondemonai,” I replied reflexively. Nonsense! “My Japanese is awful. I’ve still got a lot to learn.”

“Oi, Satō-sensei. This gaijin here says his Japanese is awful, then goes and uses a word like, ‘Tondemonai!’”

Satō rubs the sleep from his eyes says, “Heh?”

“How can I help you?”

“I’m, um, looking for a kick boxing class. You got any?”

“Kick boxing? No, I’m sorry we don’t. We do have karate, though. Tuesday and Thursday evenings. And there’s Aikido on Wednesday and Friday evenings.”

“Nothing in the afternoons?”

“No, only in the evenings.”

“Well, what about jūdō?”

The man’s eyes lit up. I was in luck, there was a class in session now, he said pointing to a separate building across the driveway.

“That building?” I said. I had my doubts.

“Yes, yes. Just go right over there. Tell them you’re an observer.”

I wasn’t sure the old man had heard me correctly, but I went to the adjacent building all the same, and removed my shoes at the entrance. As I stepped into the hall, two women in their fifties wearing what looked like long, black pleated skirts and heavy white cotton tops minced past me, their white tabi’ed feet[1] sliding quietly across the black hardwood floor. A similarly dressed raisin of a man, upon seeing me bowed gracefully, then glided off to the right from which the silence was broken with the occasional “shui-pap!”

“Anō,” I called out nervously. “I was told to come here. I’m, um, interested in learning jūdō.”

“Jūdō?” the elderly man asked.

“Yes, jūdō.”

“This isn’t jūdō,” he said, eyeing me warily. “It’s kyūdō.”

“Kyūdō?” What the hell is kyūdō?

He gestured nobly in the direction the “shui-pap!” sound had emanated from and encouraged me to follow him to a platform of sorts overlooking a lawn at the end of which was a wall with black and white targets.

“Kyūdō,” the man told me again. The Way of the Bow.

He instructed me to watch an old woman who had just entered the platform carrying a bow as long as she was short. She bowed before a small Shintō household altar, called a kamidana, then minced with prescribed steps to her place on the platform. Her posture was unnaturally rigid: her arse jutted out, spine curved back. Her head was held high. With her arms bent slightly at the elbows she raised the bow upward, bringing her arms nearly parallel to the floor. She then adjusted the arrow, stabilizing the shaft with her left hand and fitting the nock onto the string with her right hand. She turned her head ever so slowly, and, fixing her gaze on the target some thirty yards away, raised her arms, bringing the bow to a point above her head.

Inhaling slowly and deeply, she extended her arms elegantly, pulling the bowstring back with her right hand, and pushing the bow forward with her left, such that the shaft of the arrow now rested against her right cheek. The old woman paused momentarily before releasing the arrow. The string snapped against the bow with the “shui-pap” I had heard before, and the arrow was sent flying majestically right on target. It fell ten yards short, landing in the grass with a miserably anticlimactic “puh, sut!”

A small, nervous laugh snuck out before I could stop it. The old man at my side gave me a nasty look then went over to the woman who had just delivered the lawn a fatal shot and praised her effusively. She remained gravely serious, bowed deeply, then bellowed: “Hai, ganbarimasu!” I shall endeavor to do my best! All the other geriatrics there suddenly came to life and also shouted: “Hai, ganbarimasu!”

When the old woman had minced away, another man came out onto the platform and went through the very same stringent ritual. He ended up shooting his arrow into the bull’s-eye of the target . . . two lanes away. He, too, was lavished with compliments by the old man, whom I’d only just realized was the sensei, the “Lobin Hood” to these somber “Melly Men and Women”, if you will.

A third man walked onto the platform with the very same gingerly steps and bowed as the others had in front of the kamidana. Standing with a similarly unnatural posture, he went through the movements before releasing his arrow. To my surprise, the arrow actually hit the target. No bull’s-eye, mind you, but close enough for a cigar. And just as I was thinking, “Now here’s someone who finally shows a bit of promise,” the sensei marched over and ripped the man a new arsehole. His form was apparently all-wrong. The poor bastard looked thoroughly dejected as he slinked off the platform.

I went back to the Budōkan the following day to begin kyūdō lessons in earnest, not so much out of a burning passion for the martial art itself as a consequence of an adherence to the Taoist doctrine of wu wei—the art of letting be, or going with the flow: I had got this far, and was curious where it might take me. It was a mistake, although I didn’t know it at the time.

The adorable Hirose Suzu in a Kyūdō-gi.

I didn’t want the other members at the Budōkan to think of me as a mikka bōzu, that is a-three-day monk, which is what they called quitters here, but of all the martial arts I could have ended up doing, kyūdō must have been zee vurst. Being pushed around by big boys in diapers in the sumō ring would have been a vastly more entertaining.

My training progressed with unnervingly small baby steps with each visit to the dōjō. During the first several lessons, I was not allowed to even touch a bow. Instead, I was made to practice how to step properly into and then walk within the staging area. Oh yes, and how to bow reverently before the goddamn kamidana.

After weeks of mincing effeminately, I was allowed to move on to the next stage which involved going through the elaborate ritual of holding the bow, threading the nock with the bow string, aiming and releasing the arrow. Problem was, I had neither bow nor arrow and was asked, rather, to rely on my fertile imagination. Several days of this humiliation were followed by at last the opportunity to hold a bow and practice releasing imaginary arrows at an imaginary target. After the hour-long practice, I would have tea with my imaginary friends.

[1] Tabi are Japanese socks that have the big toes separate from the other toes, like mittens for your feet.

Excerpt from A Woman's Nails. To read more, go here.

© Aonghas Crowe, 2010. All rights reserved. No unauthorized duplication of any kind.

注意:この作品はフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A Woman's Nails is available on Amazon's Kindle.

God is Catholic

A few years back, I was watching the penalty shoot out between Greece and Costa Rica and found it amusing to see members from both teams praying—praying to the very same Christian God, mind you—in the hope that He was supporting their team rather than the other guys and would guide them to victory.

Indeed, one of the first things Costa Rica's Navas did after he successfully blocked the third penalty kick was to point towards Heaven and say, "Gracias!"

While 97% of Greek citizens identify themselves as Eastern Orthodox Christians—79% of them saying that they "believe there is a God" and another 15.8% describing themselves as "very religious", the highest figure among all European countries—a nationwide survey of religion in Costa Rica found that 70.5% of "Ticos" are Roman Catholics, 44.9% of whom are practicing.

Clearly this says something about the nature of God that has been in dispute since the Great Schism, the medieval division of Chalcedonian Christianity into Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) branches one thousand years ago. Namely, that God is, beyond a doubt, Roman Catholic.

(That is, unless those heathen Dutch win the whole shebang.)

Band of Brothers

After watching the HBO series Band of Brothers half a dozen times over the years[1] I finally bought the book by historian Stephen E. Ambrose upon which the series was based. Although it has taken me about six months to get through it—hard to read with a young child in the house—I found Easy Company’s tale even more engrossing in print than it had been on TV. The odd thing about a book like this is that you almost feel sad that the war and the saga come to an end. You want to go on having adventures with the guys. (View the route Easy Company took here.)

Reading Band of Brothers, I was struck by a number of things that are worth mentioning.

One is how so many people volunteered to fight in the war. If I am not mistaken, all of the original members of Easy Company were volunteers. What's more, their story was one of constant shortages. When fighting in Bastogne, for instance, they had little ammunition, no winter clothing, very little food, and yet had to contend with a major counter offensive by the German Army. The shortages were not only endured by soldiers on the front, of course. Back on the home front, all sorts of things from sugar and butter to nylon and gasoline were rationed, limiting what people could buy even if, and this is important, they could afford to buy more, meaning everyone was, to some extent, feeling the effects of the war.

Contrast that with the situation today in the U.S., where in our two most recent wars the general population was never really called on to make sacrifices. Rather than reintroducing conscription which would not have been unimaginable considering America was involved in two wars,[2] members of the National Guard and reservists were instead sent to fight in Afghanistan and Iraq. Guardsmen who often joined up thinking they’d only have to put in one weekend a month, two weeks a year were now being mobilized for twenty-four months. During the height of the Iraq War, some 28% of troops were Guardsmen or reservists. (In the meantime, their homes were being foreclosed upon. Utterly shameful.) And, instead of, say, raising the tax on gasoline at the pump to help pay for the wars, Bush (What me worry?) pushed through a second round of tax cuts. Almost as unthinkable, the government continued to give a tax break to businesses which bought gas-guzzling SUVs, thanks to a tax loophole so big you could drive a Hummer through it. (And many did.) Were average Americans asked to sacrifice? No, they were told to “get down to Disney World in Florida”. Unbelievable.

The second thing that occurred to me is how little time had passed between the end of the war and my debut on this planet of ours. I was born in the mid 60s, a little over twenty years after the end of the war in Europe. I’ve been living in Japan for longer than that now and it seems like only yesterday when I first arrived. The war, I imagine, must have still been very fresh on the minds of those who had fought it. By the 1960s, many of the veterans would have been in their mid forties, my age at the time of writing this.. (Easy Company was made up of kids when they jumped from planes into Normandy.) They would have witnessed the U.S., which had once been a reluctant entrant into that most destructive and deadly of wars, become an enthusiastic dabbler in other nation’s affairs.[3] I wonder how they felt about that.

Although my father was only fifteen when the war came to an end†, two of my uncles on my mother's side did serve. One of them was only 14 or so when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, but the war would drag on long enough for him to become old enough (17) to enlist. Imagine that. His brother who was nine years his senior was drafted and joined the US Army Air Forces.

Born in the 1960s, I grew up watching a hell of a lot of TV dramas and movies about World War II. On the boob tube there was Hogan's Heroes, one of my favorites, Combat, Baa Baa Black Sheep, and so on. Hollywood produced classics, such as The Dirty Dozen, Tora! Tora! Tora!, Kelly's Heroes, The Great Escape, A Bridge Too Far, The Bridge over River Kwai, The Longest Day, Patton, From Here to Eternity. . . And these are just the ones that I can name off the top of my head. I even played with plastic toy soldiers that were modeled after WWII soldiers and a replica machine gun. So, even though I had been born two decades after the war's end, it still felt close, far closer than what was happening in Vietnam, oddly enough.

The proximity in time of the war hit home again when as a teenager in the mid 1980s I lived in Germany. It was not unusual at the time to find buildings that showed evidence of damage due to the fighting or to see men in their fifties and sixties who were missing limbs. The grandfather of one of the families I lived with in had been a tank driver on the Eastern front and had lost an eye. Some six to eight million Germans would die in the war, that's 8 to 10 percent of the country's 1939 population.[4]There were Germans, believe it or not, who were still bitter at what the Americans had done to them. I recall one old woman giving me an earful as she recounted the “cruelty” of the Americans forcing her to bury the dead at a concentration camp. (No, I am not making this up.) Looking at the map, the closest concentration camp to Göttingen, the city where I lived the longest, was the notorious Buchenwald camp fifty miles to the southeast. At the time, it was located in the DDR, or East Germany.

Despite the hardships, many Americans endured before and during World War II, the so-called “Greatest Generation” lived through some of America’s darkest and brightest days. Sons of the Great Depression they saw a country, which had been down on its luck, muster the strength to stand up to and eventually defeat two of the most awesome military powers the world had known. They would return victors, start families, and enjoy a prosperity that expanded the middle class, making the American Dream readily available to so many people. They would go on to retire in the mid 1980s when Reagan declared that it was morning again in America. They sacrificed much, but gained much in return. I wish the same could be said today.

[1] The series was released on DVD in Japan in 2002. I am currently rewatching it for the nth time.

[2] I have long been an advocate of conscription without deferments (period) as a way to prevent war. It’s very easy to say you “support the troops” or back this military action or that if you don’t actually have skin in the game, so to speak. If it were your son who was going to be shipped off to a foreign country to fight in a war that is based on questionable grounds, you might be inclined to demand more evidence before jumping on the bandwagon. The sons and daughters of America’s congressmen should also be forced to serve in conflict zones at times of war.

[3] First Indochina War (1950-1954); Korean War (1950-1953); Second Indochina War (1953-1975); Laotian Civil War (1953-1975); 1958 Lebanon Crisis (July 15 – October 25); Bay of Pigs (1961); Cuban Missile Crisis (1961); Cambodian Civil War (1970-1975); Invasion of Dominican Republic (1965-1966). And that’s just before I was born. Sheesh!

Interestingly, there was a lull of about ten years between the end of WWII and America’s intervention in East Asian/SE Asian conflicts. There was another lull of about ten years from the end of hostilities in Vietnam until Reagan’s Grenada and other follies. Is this merely a coincidence or is roughly ten years the amount of time needed for the American public to start forgetting about the most recent war?

†He would, however, join the Navy reserves upon graduation from high school at the age of 17. He drafted and entered the Marines (don't know why) in his second year at Boston College. He would spend the next decade or so in the Marines, including one year in Japan and a stint in Korea during the war there. An injury to his hand the day before being shipped out probably prevented him from having to do any fighting in Korea and may have saved his life. Dumb luck.

My paternal grandfather ran away from home, or so the story goes, and joined the Army at the age of sixteen or so by using someone else's ID. He served in Europe during WWI. I recall seeing a picture of him once standing next to one of those massive cannons that were moved around by rail. Now that I think about it, there were quite a few vets on both sides of my family. None of my brothers, brothers-in-law nor I ever served, but a number of my nephews have. One even graduated from the Naval Academy at Annapolis a few years back and is currently training to be a fighter pilot. He's one very driven young man.

[4] 30% of Germany’s troops were killed in the War as opposed to only 2.5% of American troops, which seems awfully low by comparison. I think this points to the large number of Americans, some 16.6 million people who were mobilized for the war effort. If my calculation is correct that comes to 11.8% of the population in 1945, or roughly 20% of the male population.

Good and Bad

This was unexpected.

I read years ago that about 80% of the most commonly used English words have their origin in German. Point to something on your body or in your immediate surroundings and it may have a German cousin. Commonly used, everyday words, too, have German origins--eat (essen); go (gehen); have (haben), etc.

How about adjectives? The same is true there.

The English word "good" has its roots in the German "gut". Good's irregular comparative and superlative forms come from German as well. Better in German is besser; best, is best.

What about "bad", then? Does that also come from German? Nope. Bad in German is schlecht. schlecht, schlechter, schlechtest. So what's the etymology of "bad"?

Well, here's where it gets intersting. Middle English. It may stem from the Old English bǣddel which means "hermaphrodite, womanish man".

Toru Howaito Moka

I've been in Japan for over twenty years and have not only passed the first level of the Nihongo Nôryoku Shiken and a host of other proficiency tests, but also have a masters in the bloody language. Nevertheless, I still have trouble making myself understood from time to time.

This morning's visit to Starbucks is a case in point.

With about ten minutes before I had to head out to work, I popped into the neighborhood Starbuck's and ordered a "Tall white mocha to go." (O-mochi-kaeri-de, tōru howaito moka)

The girl turned around and started to reach for a mug cup.

"It's to go," I reminded her.

"I'm sorry."

"No worries."

But then, she grabbed a paper cup and filled it with the the house blend.

"Um, I wanted a white mocha," I said, stressing the "ho" in "howaito", which begs the question of why the Japanese insist on pronouncing "white" with a ho. They don't pronounce "what" "howatto", "why" "howai", or "water" "howattah".

"I beg your pardon, sir."

"Quite alright."

But it wasn't really. Every time these incidences of miscommunication happen to me, my confidence in the language takes a hit.

"That'll be four-hundred and twenty yen," she said. "Your drink will be waiting for you at the red lamp."

"Thank you."

And so I waited by the red lamp.

In the meantime two more customers had come in, ordered their drinks and were now waiting beside me.

Before long, the barista placed a drink on the counter and said, "Starbucks latte."

There were no takers.

"Starbucks latte," he said again.

I looked at the other customers. They looked at me and shrugged. The Starbucks latte remained unclaimed.

The barista then went about making two more drinks which the other two customers took, leaving me and the unclaimed Starbucks latte both feeling stupid.

I asked the latte if this happened to him a lot. "Every now and then," he replied. What do they do with you, I asked. "Sometimes the staff drinks me, but usually they just toss me out. It's awfully humialting." I bet it is, I replied.

After a minute or so, it finally dawned on the barista that something might be wrong. When he looked at me, I suggested, "Ho-white mocha?"

He looked towards the girl who confirmed my order, and with a heavy sigh removed the unclaimed Starbucks latte and busied himself with making my drink.

Live and Burn

A few months into this expat thang, my friend "Blad" and I went to an izakaya and, equipped with a few phrases and a working knowledge of hiragana and katakana, ordered "Yakitori!"

The waiter made a funny face asked a few questions we couldn't understand, so we said, "Yakitori KUDASAI!" and felt triumphant.

About 40 minutes later, the waiter brought out two skippy skewers of chicken.

"This isn't going to do it," I said to my friend and suggested ordering some more.

He replied, "Let's just go home."

Two months later and now equipped with a few kanji and a few more phrases, we went to a proper yakitori-ya and I'll be damned if we could read even 5% of the menu.

On one of the boards, there was something written in katakana, which HAD to be something western, so we ordered that.

15 minutes later a black, winged animal with a skewer through its head and eyeballs staring back at us was brought to our table.

What the hell is this?!?!

In that great democratic tradition, we jankened to see who would be the jackass who had to eat it.

Blad lost.

As he bit into it, I asked how it tasted.

"Crunchy."

Defeated, we returned home where I consulted my dictionary which informed me that スズメ was not bat as we suspected, but sparrow.

Live and burn.

Despite losing limbs every time I stepped on a landmine like that, I miss the adventure. You learned something every day, or you went home.

Bombs Away

Wayne—BoomBoom—LaDerrière, the head of the National Bomb Association, lobbed a verbal grenade at critics following the bombing at the Boston Marathon and calls for tougher bomb-control laws. We have included an excerpt of LaDerrière’s speech here:

"As spectators, we do everything we can to keep our athletes safe. It is now time for us to assume responsibility for their safety at sporting events. The only way to stop a monster from killing our sports heroes is to be personally involved and invested in a plan of absolute protection. The only thing that stops a bad guy with a bomb is a good guy with a bomb.

"Now, I can imagine the shocking headlines you'll print tomorrow morning: 'More bombs,' you'll claim, 'are the NBA's answer to everything!' Your implication will be that bombs are evil and have no place in society, much less in our sporting events. But since when did the word 'bomb' automatically become a bad word?

"A bomb in the hands of a Secret Service agent protecting the President isn't a bad word. A bomb in the hands of a soldier protecting the United States isn't a bad word. And when you hear the glass shattering in your living room at 3 a.m. and call 911, you won't be able to pray hard enough for a bomb in the hands of a good guy to get there fast enough to protect you.

"So why is the idea of a bomb good when it's used to protect our President or our country or our police; but bad when it's used to protect our athletes in their sporting events?"

"I call on Congress today to act immediately, to appropriate whatever is necessary to put police officers armed with explosive belts or suicide vests at every major sporting event - and to do it now, to make sure that blanket of Semtex is in place when our athletes return to their next game, match, or race."

"Before Congress reconvenes, before we engage in any lengthy debate over legislation, regulation or anything else, as soon as our sportsmen and sportswomen return to the field, court or pitch, we need to have every single stadium, gymnasium, court and racetrack in America immediately deploy a protection program proven to work - and by that I mean security armed with grenades, mortars, and plastic explosives, embedded with nuts and bolts and nails.

"Right now, today, every stadium, gym and aerobics club in the United States should plan meetings with instructors, coaches, administrators, team owners, and local authorities - and draw upon every resource available - to erect a cordon of destruction around our athletes right now."

"There'll be time for talk and debate later. This is the time, the clock is literally ticking, this is the day for decisive action.

"We can't wait for the next unspeakable crime to happen before we act. We can't lose precious time debating legislation that won't work. We mustn't allow politics or personal prejudice to divide us. We must act now, never forgetting that bombs don’t kill people, people do."

Unemployment and Welfare in Japan

While this is old news, it is still interesting. (I will try to find more up-to-date stats later.)

The upper graph shows the persentage of people in each prefecture who received welfare benefits (生活保護, seikatsu hogo) in 2010. Starting from the left, the rate for the entire nation (全国) is 15.2%. Next is Hokkaidô (北海道) at a whopping 29%. Aomori, 20.8%. 19.5% of the residents of Tōkyō (東京) are on welfare; 15.3% in Kanagawa (神奈川). Ōsaka (大阪) has the largest number of welfare recipients at an unbelievable rate of 32%, meaning some 2.8 million people in the prefecture are receiving benefits. Kōchi (高知) on the island of Shikoku has a rate of 26%. In the prefecture of Fukuoka, where I live, 24.1% of the population is getting government aid, the fourth highest in the nation. Interestingly, in neighboring Saga prefecture (佐賀) the rate is only 8.7%.

The red line indicates what the rate was in 1997. In every single prefecture the rate went up, in many cases doubling.

2010 was not a bumper year in Japan. Thanks the what the Japanese call "The Lehman Shock" (and I call "The Panic of 2007-2008"), the official unemployment rate was at its highest level since the 2002 recession following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It has since come down and now hovers between 3.5% and 4%, or at about the same level that was seen in 1997 when the Asian financial crisis threatened a global economic meltdown. (So many economic crisises are bad for the heart.) I would think that the percentage of those who are receiving welfare benefits today has also come down. (I'll have to look into that.)

One thing that struck me, actually several things did, but one thing that impressed me is how larger, vibrant cities like Fukuoka had such high welfare rates, while places like Saga which, I'm sorry to say, don't have a whole hell of a lot going for them—the same could be said of Hokuriku (Toyama 富山, Ishikawa 石川, etc.)—have such low rates. My theory for this is that the younger stratum of the population has left for bigger cities to look for work, lowering the welfare rates of their home towns, but raising them in the cities. (Visit Saga city on a Sunday afternoon and I challenge you to try to find a person in his or her 20s. They just aren't there.)

The second graph shows unemployment rates on the X axis and welfare rates on the Y axis. As one might suspect, there is a positive correlation between the two: the higher the unemployment rate, chances are the welfare rate will also be high. Fukuoka (福岡), again, had the fourth highest rates in the country in 2010.

Here is information from 2018:

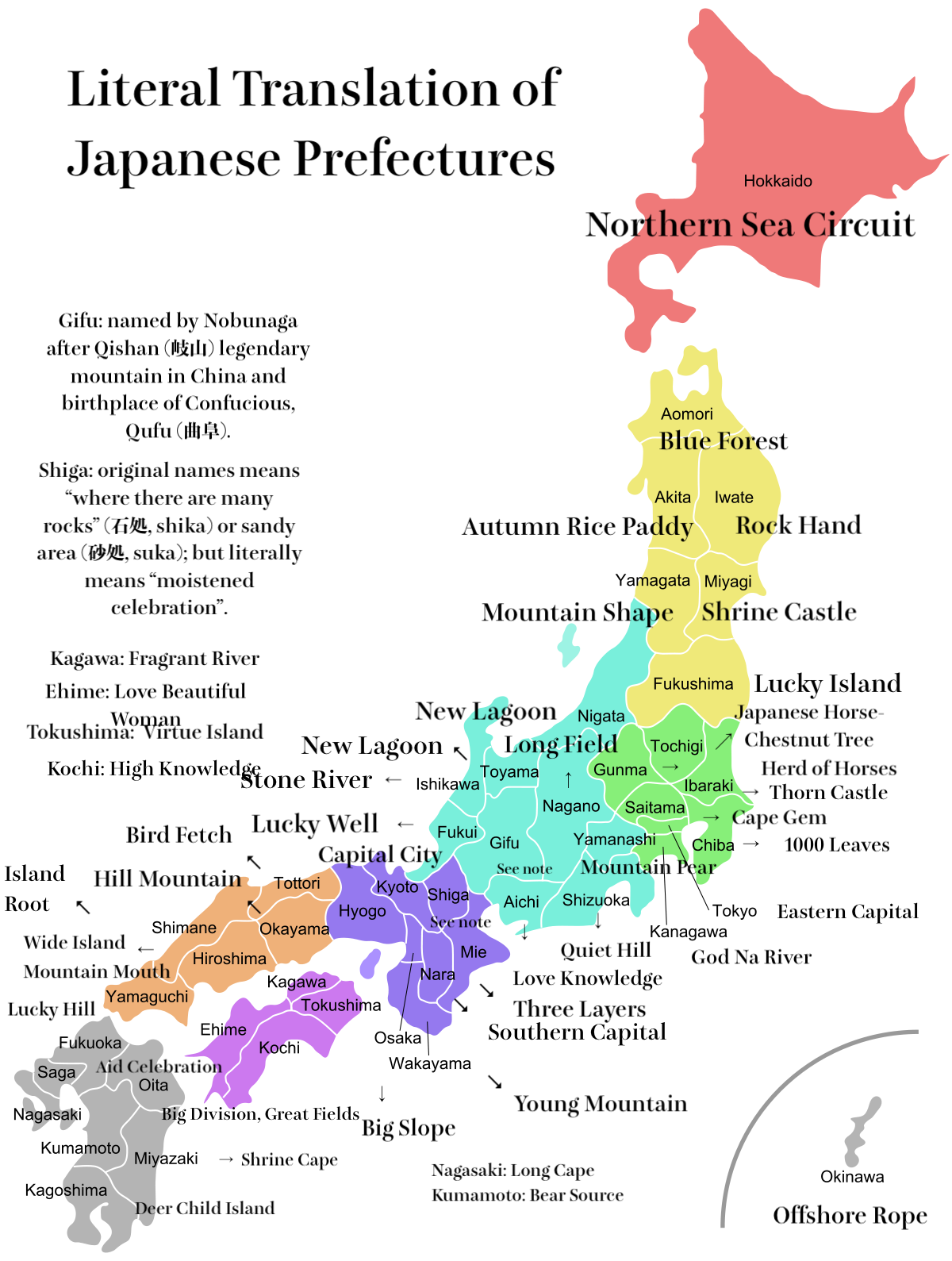

Literal Translation of Japanese Prefectural Names

北海道

Hokkaidō: literally Northern Sea Circuit or Road.

In the Ainu language, it is called アイヌ・モシル, Aynu mosir, which means "Land of the Ainu [people]". Hokkaido was formerly known as Ezo, Yezo, Yeso, or Yesso. Six names for the region were proposed in the Meiji Period, including Kaihokudō (海北道) and Hokkaidō (北加伊道). Hokkaidō written 北海道 was chosen, one, for its similarity to 東海道 (Tōkaidō), and, two, because the Ainu called the region Kai.

青森

Aomori: literally “Blue Forest”

The Japanese word for blue (青) can also mean dark green, so Aomori could be translated as “green forest”. The name Aomori comes from the village of Aomori to which the capital of the newly established prefecture was moved in September of Meiji 4 (1871). The name Aomori had been given to a newly constructed port in the Hirosaki Han (feudal domain) in the early Edo Period (1624). It is said the name originated from the dark green forests that could be seen from the sea.

Ao(i) (青い) is used for a number of things in nature: 青葉 (aoba, “green leaves”, 青りんご (aoringo, “green apple”), 青々とした新緑 (aoao toshita shinryoku, “lush new green leaves”). Green traffic lights (青信号, aoshingō; lit. blue signal) reflected the color found in nature.

秋田

Akita: lit. “Autumn Rice Paddy/Field”

Probably named after the military settlement called “Akita Jō that was built in 733. The fort was the base from which operations to colonize the region and subdue the native Emishi people (lit. “shrimp barbarians”), an ethnic group, possibly distinct from the Ainu and Jōmon, who lived in the Tōhoku region.

岩手

Iwate: lit. “Rock Hand”

Several theories about the origin of the name "Iwate" exist, but the most well known is the tale Oni no Tegata, which is associated with the Mitsuishi or Three Rocks Shrine in Morioka. The rocks are said to have been thrown down into Morioka by an eruption of Mt. Iwate. According to the legend, there once was a devil who tormented the local people. When the people prayed to the spirits of Mitsuishi for protection, the devil was immediately shackled to these rocks and forced to make a promise never to trouble the people again. As a seal of his oath, the devil made a handprint on one of the rocks, thus giving rise to the name Iwate.

山形

Yamagata: lit. “Mountain Shape”

The name comes from the name of a town, Yamagata (山方), meaning near the mountains.

宮城

Miyagi: lit. “Shrine Castle”

The name was taken from the centrally located Miyagi Gun (county or district) when the name changed from Sendai Prefecture in 1872.

新潟

Niigata: lit. “New Lagoon”

Named after the capital of the prefecture. The city itself was named after a place name that was recorded in 1520. The reason for the name, however, was not written, but several theories exist. One, there was a kata or lagoon at the mouth of the Shinano River. Another theory states that in the Shinano River a new island built up naturally over time and was the site of a hamlet called Niigata, but spelt with a different kanji, 新方. And so on.

福島

Fukushima: lit. “Lucky Island”

The prefecture is named after Fukushima-jō, a castle that has undergone a number of name changes over the years. Originally called Daibutsu-jō or Osaragi-jō (大仏城, lit. “Great Buddha Castle”), the Date Clan called it Suginomejō (杉目城 or 杉妻城). In 1592, the area was conquered during the Warring States Period in the late 16th century and became the center of the domain. It was renamed Fukushima as this was considered a more auspicious name.

群馬

Gunma: lit. “Herd [of] Horses”

Originally Kuruma no Kōri, where Kuruma was written with a single character (車, wheel or vehicle). In the early Nara Period (710-794), it became popular to name counties (郡, kōri) or and countries (郷, gō) with two kanji. Gunma, which means “horses herd together”, became the new name. From ancient times, the area had been known as a place where valuable horses roamed.

栃木

Tochigi: lit. “Japanese Horse Chestnut Tree”

Tochigi Prefecture is one of three prefectures, the other two being Yamanashi and Okinawa, in which the capital is located in a city with a name different from the prefecture’s. In the case of Tochigi, the capital is located in Utsunomiya. Tochigi City, however, did serve as the capital city for a spell during the Meiji Period and the prefecture was named after the capital at that time. The name of the city is believed to have come from Japanese horse-chestnut trees that were located in the center of the land that became the city. Another theory is that the name actually means “ten chigi” (十千木, pron. “tōchigi”). Chigi are forked roof finials found in Japanese and Shinto architecture.

茨城

Ibaraki: lit. “Thorn Castle”

There is a lot of confusion as to how to read 茨城. Many people, including myself say “IbaraGI”. The problem was so common, the prefecture conducted an online campaign to teach the correct pronunciation “IbaraKI”, but sometimes you just can’t teach old dogs new tricks. There are three main reasons for the mistake. For starters, that’s how they say the prefectural name in the local dialect, so, um, what’s the problem; two, IbaraGI City in Kansai, which is spelled with the same kanji; and, three, the prefecture MiyaGI which uses the same kanji (城). The name Ibaraki comes from Ibaraki District (茨城郡) in the center of the prefecture. There are two theories regarding the name. One claims that a warrior from the imperial court named Kurosaka no Mikoto destroyed the indigenous tribes wielding thorny branches as weapons. Another theory is that a castle of thorns was built to protect people from bandits. Both stories are similar to other legends that were promoted to establish the authority of the Yamato race as its influence spread throughout Japan.

富山

Toyama: lit. “Wealth/Prosperous Mountain”

The name has its roots in the Muromachi Period (1336~1573) when the area was called 越中国外山郷 (Etchū no Kuni Toyoma-gō), or the “Outer Mountains of Etchū Province”. Toyama spell 富山 was first seen in the Sengoku (Warring States) Period (1467~1615). By the Edo Period (1603~1868), both spellings were being used.

長野

Nagano: lit. “Long Field”

May be a reference to the Nagano Basin of the Chūbu Region. Following the Meiji Restoration, Nagano became the first established modern town in the prefecture on April 1, 1897.

埼玉

Saitama: lit. “Cape Gem”

The name come from Sakitama Mura (埼玉村) in Saitama District, modern-day Gyōda City, and is believed to have originated from the Sakitama Kofun in the city and may have come from the name Sakitama (埼魂), meaning the action of the gods to bring fortune. Another theory states that it comes from Sakitama (前玉 or 佐吉多万) which are mentioned in the Nara Period collection of waka poetry, Manyōshū (万葉集) which was compiled after 759. The pronunciation of Sakitama predates Saitama and reflects a ki→i shift, known as the i-onbin. Examples include:

「埼玉」 サキタマ → サイタマ

「大分」 オオキタ → オオイタ

「次手」 ツギテ → ツイデ 「ついで」

「月立ち」 ツキタチ → ツイタチ 「朔日」

「咲きて」 サキテ → サイテ 「咲いて」

「急ぎて」 イソギテ → イソイデ 「急いで」

「高き」 タカキ → タカイ

「久しき」 ヒサシキ → ヒサシイ

This same shift can be seen in the dialects of western Japan where しないで is often pronounced せんで or せいで: (セズテ → センデ → セイデ). If I am not mistaken, the shift took place in the Heian Period. (Still trying confirm this.)

千葉

Chiba: lit. “One Thousand Leaves”

There are a number of theories regarding the origin of the prefecture’s name. One of them comes from a sakimori no uta (防人歌), a poem in the Manyōshū collection (Vol. 20, 4387), penned by a soldier who was sent to protect the northern coast of Kyūshū. The conditions under which a sakimori traveled and lived were often harsh and their poems reflected this. Ōtabe no Tarihito was one such soldier from the District of Chiba in Shimōsa Province and he penned the following poem:

Original written in man’yōgana:

Original written in man’yōgana:

知波乃奴乃

古乃弖加之波能

保々麻例等

阿夜尓加奈之美

於枳弖他加枳奴

Transliteration:

千葉の野の

児手柏の

ほほまれど

あやに愛しみ

置きて高来ぬ

Romanization:

Chiba no nu no

Konotekashihano

Hohomaredo

Ayanikanashimi

Okitetagakinu

Modern Japanese: 千葉の野の児手柏(このてかしわ)の若葉のように、まだ初々しくて可愛いいあの子を置いてはるばるやってきた。

Interpretation: 千葉の野の、児手柏(このてかしは)の(花のつぼみの)ように、初々しくってかわいいけれど、とてもいとおしいので、何もせずに(遠く)ここまでやってきました。

English Translation: I’ve come from far away, leaving that pure and innocent girl behind like the young leaves of konote oak of the Chiba meadow,

東京

Tōkyō: lit. “Eastern Capital”

Originally a fishing village, named Edo (江戸, lit. “bay/inlet entrance” or “estuary”), the city became the de facto political center of Japan in 1603 as the seat of the Tokugawa Shōgunate. When the shōgunate fell in 1868, the imperial capital of Japan, along with the imperial family, was moved to Edo and the city renamed. The addition of the kanji 京 (kyō) was in line with the East Asian tradition—Beijing (北京, Norther Capital); Nanjing '(南京, Souther Capital), etc.

福井

Fukui: lit. “Lucky Well”

The name of the prefecture was originally written 福居 and refers to the castle that was built on the ruins of Kitanoshō Castle in 1601 by the second son of Tokugawa Ieyasu following his victory in the Battle of Sekigahara the year before. The castle was renamed "Fukui Castle" by the third daimyō of Fukui Domain, Matsudaira Tadamasa, in 1624 after a well called Fukunoi, or "good luck well", the remains of which can still be seen today.

岐阜

Gifu: Wanting to be considered not only the unifier of Japan but also a great mind, Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) named the region’s capital Gifu, after Qishan (岐山), a legendary mountain in China and Qufu, the birthplace of Confucius (曲阜).

愛知

Aichi: lit. “Love and Knowledge”

Aichi was the name of the gun (district) which was located where the downtown of modern-day Nagoya City is located and was originally written ayuchi (年魚市) and refers to the Ayuchigata Inlet, mentioned in the Manyōshū collection of classical Japanese poetry of the Nara Period.

「桜田へ鶴(たず)鳴き渡る―潮干にけらし鶴鳴き渡る」

〈万葉集•271〉

意味・・桜田の方へ、あれあのように鶴が群れ鳴き渡って いく。 これで見ると、年魚市潟は潮干したものと 見える。 だから餌を求めて鶴が、あんなに鳴いて 羽ばたいて行くよ。 鶴は干潟に降りて餌を漁(あさ)る習性があるので 年魚市潟の方に飛んで行く鶴を見て潮干になった と想像して詠んだ歌です。

静岡

Shizuoka: lit. “Quiet Hill”.

Named after the Shizuoka Domain that existed in the area from 1869 to 1871 and was centered at Sunpu Castle (駿府城). Prior to that, the feudal domain was called Sunpu-han. The name Shizuoka was decided in 1869 by the political reforms of the hansekihōkan (版籍奉還) royal charter of July 25th of that year. The area around the prefectural office was known as fuchū (府中). Due to the similarity with the synonym fuchū (不忠, lit. “disloyalty”), the Meiji government suggest three other options: Shizuoka (静岡), Shizu (静), Shizujo (静城). The roots of the name “Shizuoka” itself is derived from Shizuhata-yama (賤機山), a 171-meter high mountain in the prefecture. Another word for 賤 (shizu) is iyashii (卑しい) which can mean “greedy”, “vulgar”, “shabby” or “humble”, as in a person of humble birth (卑しい生まれの人).

山梨

Yamanashi: lit. “Mountain Pear”.

From Yamanashi-gun, which was named after a famous ancient pear tear in the mountain behind the Yamanashi Oka Shrine in the Kasugai district (春日居町). There is a tendency to believe that the name derived from the mountain peaches that grew in the area, but according to the Fūdoki (風土記)—ancient reports on provincial culture that were presented to the monarch, and are considered to be the oldest written records from the Nara Period (710-794)—Yamanashi was formally written 山無瀬, 夜萬奈之, and 山平らす (Yamanarasu) in reference to the lack of hills and peaks in the Kōfu Basin (甲府盆地). Over time, Yamanarasu became Yamanashi. In the year Wado (和銅) 6 or 713 AD, the Wadokanrei was passed whereby the names of the provinces had to be written by the most commonly used version in existence at the time. Yamanashi written 山梨 was chosen.

滋賀

Shiga: lit. “Where there are many rocks”.

When the han system was abolished in 1871, eight prefectures were formed in the former Omi Province. A year later, they were unified into Shiga Prefecture. The name "Shiga Prefecture" came from "Shiga District" (滋賀郡) because Otsu, a city on the western coast of Lake Biwa and the capital of the prefecture today, was part of it. As for the origin of the name, there are several theories. The most dominant one claims that it comes from shika (シカ, 石処) which means “place with many stones”. The abundance of other “rocky” areas similarly named Shika have given this theory credence. Another claims that the name comes from suka (スカ, 砂処), meaning wetland or shoal (tidal sandbar).

Finally, there is some conjecture that the name derives from Shika no Shima (志賀島) in Hakata, Fukuoka, which was ruled by the Azumi people (阿曇氏), a seafaring warrior tribe in northern Kyūshū.

三重

Mie: lit. “Three Layers”.

The name Mie is believed to have been taken from the final words of Yamato Takeru (日本武尊 or 倭建命), a semi-legendary prince and son of the 12th Emperor of Japan who died in the Ise Province. As he was traveling from the region of modern-day Kuwana City (桑名市) towards Kameyama City to the south he passed through Mie district, where according to the Kojiki, he said:

Classical Japanese: 吾が足は三重の勾がりの如くして甚だ疲れたり

Transliteration: Wagahai-ga ashi-wa Mie no magari no gotokushite hanahada tsukaretari.

Modern Japanese: 私の足は三重の曲り餅のようになって、とても疲れた。

Translation: My legs were exhausted like twisted Mie magari-mochi.

Notes: まがり餅は米をこねて曲げてあげたお菓子。果たして「まがり」が「まがり餅」だと直結できるのかはよくわかりませんが――まぁ「三重のマガリのごとく」という文章から言うとまがり餅というか「三重のまがり」という造形のお菓子があったという方がすっきりしますね。それだけ「ヘトヘト」という意味でしょう。 ちなみにネットで見ると三重では鉄工業が盛んでその公害で足が曲がった人が実際にいた、という話を見かけましたが、うーん、まぁ、ねぇ。

京都

Kyōto: lit. “Capital City”.

Kyōto was originally called Kyō (京, capital; metropolis), Miyako (都, the capital), or even Kyō no Miyako (京の都) until the 11th century, when the city was renamed "Kyōto" (京都, lit. "capital city"), after the Middle Chinese kiang-tuo (or jīngdū in Mandarin). When the imperial palace moved from Kyōto to Tōkyō in 1868, Kyōto was briefly known as Saikyō (西京), or Western Capital, contrasting it from Tōkyō, the “Western Capital”.

Throughout Eastern Asia in ancient times, the city where the Tenshi (天子) or emperor lived was called Kyō (京) or Keishi (京師), meaning the “capital”. During China’s Jin Dynasty (266-420), however, the character 師 was often used in the “temple names” of emperors, so to avoid confusion—i.e. is this the name of a city or is it someone’s name—都 was adopted.

When Heian-kyō was first being established as the new capital, there was no consensus on how to call it and so the city was called by a number of names: Kyō, Keishi, and Kyōnomiyako.

奈良

Nara: lit. “Flat Land”

A number of different characters have been used to represent the name Nara, including 乃楽, 乃羅, 平, 平城, 名良, 奈良, 奈羅, 常, 那良, 那楽, 那羅, 楢, 諾良, 諾楽, 寧, 寧楽 and 儺羅. The most widely accepted theory for the name of the prefecture (i.e. “Flat Land”) comes from a 1936 study of place names by folklorist Kunio Yanagita (1875-1962) in which he wrote, “"the topographical feature of an area of relatively gentle gradient on the side of a mountain, which is called taira in eastern Japan and hae in the south of Kyushu, is called naru in the Chūgoku region and Shikoku (central Japan). This word gives rise to the verb narasu, adverb narashi, and adjective narushi." Other theories argue that the name is derived from from 楢 nara, meaning "oak”; that it means “to flatten or level (a hill)”; or that it comes from the Korean nara (나라: "country, nation, kingdom").

兵庫

Hyōgo: lit. “Troops Storage”

Named after the castle Hyōgo-jō that belonged to the Amagasaki Domaine and stood at Nakanoshima, Hyōgo Ward from 1581 to 1769. During the Edo Period, it became the seat of the jinya (陣屋) or an administrative headquarters for the province and housed the head of the administration and grain storehouse. Domains assessed at 30,000 koku (4.5 million kilograms) or less of rice had jinya instead of castles. The name itself dates back to Emperor Tenji (天智天皇, 661-672) when there was a tsuwamono (兵) gura (庫), or a place to keep warriors and weapons.

大阪

Ōsaka: lit. “Big Slope”

Wiki: Ōsaka means "large hill" or "large slope". It is unclear when this name gained prominence over Naniwa, but the oldest written evidence for the name dates back to 1496. By the Edo period, 大坂 (Ōsaka) and 大阪 (Ōsaka) were mixed use, and the writer Hamamatsu Utakuni, in his book "Setsuyo Ochiboshu" published in 1808, states that the kanji 坂 was abhorred because it "returns to the earth," and then 阪 was used. The kanji 土 (earth) is also similar to the word 士 (knight), and 反 means against, so 坂 can be read as "samurai rebellion," then 阪 was official name in 1868 after the Meiji Restoration. The older kanji (坂) is still in very limited use, usually onlyin historical contexts. As an abbreviation, the modern kanji 阪 han refers to Osaka City or Osaka Prefecture.

和歌山

Wakayama: lit. “Poem Mountain”

「和歌山(わかやま)」の語源・由来は、「和歌浦」の和歌と「岡山」の山との合成語とされている。住所表記での「和歌浦」は「わかうら」と読むために、地元住民は一帯を指して「わかうら」と呼ぶことが多い。狭義では玉津島と片男波を結ぶ砂嘴と周辺一帯を指すのに対し、広義ではそれらに加え、新和歌浦、雑賀山を隔てた漁業集落の田野、雑賀崎一帯を指す。名称は和歌の浦とも表記する。

『万葉集』にも詠まれた古からの風光明媚なる地で、近世においても天橋立に比肩する景勝地とされた。近現代において東部は著しく地形が変わったため往時の面影は見られないが、2011年にようやく国の名勝に指定され、また自然海岸を残す西部の雑賀崎周辺は瀬戸内海国立公園の特別地域に指定されており、それぞれ保護されている。岡山城(おかやまじょう)は、紀伊国(和歌山県和歌山市岡山丁)にあった日本の城。岡城とも呼ばれる。

沖縄

Okinawa: lit: “offshore rope”

In his Okinawa: The History of an Island People, George H. Kerr writes: “‘a rope in the offing’ . . . is an apt enough description for the long narrow island which dominates our story. On a map the island chain itself suggest a knotted rope tossed carelessly upon the sea. The southernmost island (Yonaguni) lies within sight of Formosa on an exceptionally clear day; the northernmost, severn hundred miles away, lies just off the tip of Kyushu Island in Japan." Between these two points are 140 islands and reefs, but only thirty-six now have permanent habitations on them.” Locally, the name of prefecture is pronounced Uchinaa.

Why was Setsubun on February 2nd?

Many people on SNS have noted that Setsubun, the eve of risshun (立春), or the first day of spring according to the lunisolar calendar (tai'in/taiyō reki, 太陰太陰暦), fell on February 2nd for the first time in 124 years. The last time this happened was Meiji 30 or 1897.

But why is this?

Like many “uniquely" Japanese traditions, risshun is actually one of the 24 solar terms of the Asian calendar which originated in China, but spread throughout the East Asian cultural sphere. In China, it is known as Lìchūn and begins when the Sun reaches the “celestial longitude of 315° and ends when it reaches the longitude of 330°. It should be noted that each of the 24 solar terms are spaced 15° apart along the ecliptic, or the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

It takes the Earth 365.2422 days to orbit the Sun and because of that 6 hour difference, the exact time at which the four annual setsubun (yes, four) occurs differs from year to year. Today, we add one extra day to the year every four years, or every leap year. The leap year in Japan is called urūdoshi (閏年). Before the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, each month in Japan lasted 30 days, with the year lasting only 354 days. In order to make up for the loss of 11 days a year, an urūtsuki, or “leap month”, was added every three years.

Incidentally, each solar term is divided into three pentads, or (候, hòu in Chinese; kō in Japanese), meaning there are actually 72 pentads or “micro seasons” in Japan, rather than the exalted four. The present micro season or kō is Harukaze Kōri-wo Toku (東風解凍, also tōfū kaitō) and means “Spring (or Eastern) winds thaw the ice."

The next solar term is Usui (雨水, yǔshuǐ in Chinese, ushii in Ryūkyūan) will fall on February 19th and refers to spring rain.

If you would like to know before hand what day Setsubun will fall on, divide the year by four. From 2021 to 2057, if 1 remains, Setsubun will fall on the 2nd; if two, three, or zero remains, Setsubun will fall on the 3rd. Because of this Setsubun will fall on the second of February every four years from 2021 to 2057.

Vacation Pay, Then and Now

When looking into the value of a hundred yen at the end of the Pacific War, I came across a number of interesting comments and anecdotes. One person claimed—and I have yet to fact check this—that a junior high school graduate’s starting salary in 1945 was about 100 yen. An employee in those days would be expected to work ten hours a day, and would be given only two days off a month. Paid vacation did not exist seventy years ago. By 1946, starting salaries rose to four or five hundred yen due to the effects of the post-war inflation and shortages. 100 yen in 1946, could be said to be equivalent to about fifty thousand yen today.

A week ago, I was talking with a woman who worked for a company that runs a number of fashionable hotels and restaurants throughout Japan and in LA and Manhattan. She was on holiday at the time, explaining that she was entitled to take a total of twenty-two days paid vacation every year. Many companies in Japan give lip service to paid-holidays, but few actually let them take so many days off. The woman had taken off eleven days in order to travel to Kansai. She said she was going take another eleven days off in the summer and travel to America.

When I first came to Japan, most people, including me, worked six days a week. The Prime Minister at the time, Kiichi Miyazawa (yes, that long ago), declared that he wanted to make Japan the world’s leading country regarding lifestyle and leisure. It made me laugh at the time. Even if companies offered their employees paid vacations, none of them could actually take time off. If you wanted to use the benefit, you normally had to resign from your job first. Masao Miyamoto wrote of this in his highly-recommended Straightjacket Society.

Things, I'm happy to say, really have improved for many workers in Japan over the past two decades. There have, no question about it, been a lot of losers, too—part-timers, contract workers, and the like—but that’ll have to wait until another post.

Maybe you can buy love

According to the Tokyo Reporter, police in Fukuoka arrested seven suspects on Tuesday for registering non-existent users on an Internet matchmaking site. “Officers from the prefecture’s anti-cybercrime division took Keiichiro Yokomizo, 37, the former president of Garage Inc., and six employees into custody for defrauding 45 members of the deai-kei (or encounter) dating site Deai BBS out of 85 million yen.”

“Deai BBS had 120,000 male and female members on its books. Since its establishment in 2005, the site generated over two billion yen in revenue. According to police, the majority of its users consisted of sakura, or fake, profiles fabricated by company employees.”

120,000 members!!!

2 billion yen!!!

About ten years or so ago, a young university coed told me that she had recently interviewed with a company that ran one of these so-called “deai” (encounter) sites. She had been looking for a part-time job, something to do in the evenings after school and came across a want-ad seeking young women with “computer-related experience” for “clerical work”. She called them up and arranged an interview.

As soon as she had entered the company’s office, she suspected that something was not kosher.

There was a large room with banks of computers, she told me. A small army of young women were typing away on keyboards or sending text-messages from cellphones. All of them were the sakura, women hired to send messages to the male subscribers to entice them to reply (for a fee, of course) in the hope of eventually setting up a date that would never, ever take place, not even if pigs flew and hell froze over.

The manager, a flashy young man of only twenty-four years of age, tried his best to sell the student on the merits of the job: good pay, hands-on experience using computers and business software, and the chance to have fun “role-playing”.

“Um. I don’t think I could ever . . .”

“Sure you can!”

“No, it just doesn’t seem right to me.”

“Think of it as helping these guys. You’re giving them hope, a dream. You’re putting a skip in their step.”

“I would be deceiving them,” she said and stood up to leave.

“Well, if you ever change your mind . . .”

The TR article continues: “One victim, a 25-year-old male from Fukui Prefecture, was allegedly defrauded out of 160,000 yen ($1,539) between February 5 and March 24 of last year. A Kanagawa man, over the age of 70, was swindled out of 10 million yen ($125,000), while a woman in her 30s from Aichi Prefecture lost 20 million yen ($192,000).”

You’d think that a person would start to wise up after losing only 10,000 yen ($125), but guess again. Fools and their money, the saying aptly goes, are soon parted, much faster and easier than I thought.

“Saki”, another woman I know, confessed to me the other day that she had registered with a matchmaking service in November. While she has no trouble meeting or dating men, she has reached the age where she wants to settle down with someone and start a family.

Late last summer, Saki had seen an interview on TV of a woman who ran a successful matchmaking business in Tōkyō. The key to the woman’s success, she claimed, was her selectivity in choosing clients. Saki immediately called her up and made arrangements to meet with her the next time she was in the metropolis.

As the matchmaker deals mostly with clients in the Kantō area [1], she said couldn’t make any promises to Saki, whose first priority was finding a partner who lived closer to Fukuoka.

I was curious how much the service cost. The sign-up fee, Saki told me, was 100,000 yen ($960)—though she was able to get the price knocked down to 30,000 yen ($288) because she didn’t live in Tōkyō. There was also a “modest” fee of 10,000 yen ($104) for arranging an initial date with a prospect, which Saki has already done—she will meet Mr. Goodbar this Sunday. And, in the event that this or another one of these encounters actually leads to marriage, she will have to pay the matchmaking service a final fee of 300,000 yen. ($2,885).

“What if you just don’t tell them about the marriage?” I asked.

She replied that a friend of hers also suggested doing the same thing, but then added that she would be so happy to have finally found someone that she probably wouldn’t mind paying.

I hope everything works out for Saki.

Follow up: Seven years later, Saki is still single.

The photos above are from the Twitter account of a Thai woman named ViennaDoll who shares Ideal vs Reality photos that are a riot. Have a look.

[1] The Kantô region includes the Greater Tokyo Area and encompasses seven prefectures: Gunma, Tochigi, Ibaraki, Saitama, Tokyo, Chiba, and Kanagawa.

Worm's-Eye View of Tokyo

The End is Nigh

Two thoughts occured to me when I saw this photo.

One, the end is not as nigh as some would like; and, two, we've clearly got plenty of time to repent, so go ahead and enjoy yourself.

If anything is true, God is not in a hurry.